Expert Speech Skill: Pillars Of Eternity Interview Part 2

Darklands, Wastelands and New Lands

In the second and final part of a conversation with Josh Sawyer of Obsidian (part one), we discuss how the design of Pillars of Eternity differs from Fallout: New Vegas. That involves a discussion of New Vegas' post-release support, official and otherwise, and the pros and cons of traditional RPG systems. Of particular note - why Pillars of Eternity does not have a Speech skill, or any other skill of that sort.

With contributions from executive producer Brandon Adler, we also discuss the role of Paradox as publisher and the benefits of digital distribution, and end with a tribute to nineties RPG, Darklands.

RPS: Is it true that you carried on modding New Vegas after release?

Sawyer: Yeah. I haven’t done any work on it in a long time though.

RPS: It seems like a game that had lots of potential for modding and I’ve always wondered if that was an intentional part of the design. There’s a great mod that lets you start with different backstories and in different locations. Many games wouldn’t support that because there are no interesting things occurring in the world until certain targets have been hit elsewhere. What were you trying to achieve with your work?

Sawyer: In a game that’s very exploration-based, of course it’s important for players to be able to go in any direction they want and find interesting things. We didn’t want places to feel isolated – there are a couple of exceptions – but we didn’t want the New Vegas world to feel like separate isolated chunks.

As far as the modding that I did goes, I wanted to do things that I couldn’t do for the released game, like fixing bugs that I wasn’t allowed to fix in patches. But I also wanted to make it, game balance wise, something…

RPS: You slowed it down, right?

Sawyer: I slowed advancement down. I changed the balance on a lot of stuff. It’s a significantly harder game overall. The weight limitation is much much stricter – like a third or a quarter. I designed the game to be played in hardcore from the start and you do have to pay a lot more attention to water. It’s a lot less common, kinda scarce actually.

I kind of made it a little more simulationist overall and more challenging. I dealt with stuff that I wasn’t able to address with the commercial release.

RPS: One of the rare things that New Vegas addresses is that the mechanics, in hardcore mode, fit the theme to an extent. That’s not often the case in RPGs because rulesets tend to carry across regardless of theme but New Vegas takes the idea of the Wasteland and, to an extent, attempts to reflect that in its rules.

Sawyer: I kinda felt like the conflict in New Vegas is about water and power, which is classic (laughs). Lots of people have fought over power and water in history.

RPS: Chinatown!

Sawyer: Yeah! We actually have a Chinatown-related quest. But because of the struggle for water, the layout of the world should reflect our theme and so should some of the mechanics. I was pretty strict – and I think there might be one exception to this – on having every community have a water tower and water merchants travelling around. If you go to the sharecropper farms you can see the pipes that carry the water. We wanted people to realise how important this was.

Having the player need to drink water emphasises that even more. It’s in the story, in the world and in your routines. All of those things together tell you that this is a harsh place to live in. We’re not just saying it, we’re showing it and making you participate in it.

RPS: It’s not just something that’s mentioned in an intro movie and never brought up again.

Sawyer: Exactly!

RPS: Do you do anything similar in the design of Pillars of Eternity? Is there a way to make those Infinity Engine style rules work with the themes and story?

Sawyer: I think it’s harder in a game like this. So many of the mechanics are very D&D-ish.

Early on, and this isn’t going to happen now, we had some ideas that people might still be interested in. We use souls, your own and other peoples’, as a justification or a reason as to why powers work the way that they do. But ultimately, many of the ways that those powers work, mechanically, are locked into existing ideas. They’re not necessarily executed exactly how you’ve seen before but we are a little limited in how we can build our classes because we want them to be understood by a D&D audience. We can’t go too heavy on the souls.

So we don’t move too far away. A lot of people will come to this game and make one character that they use in all of these kind of games. A sneaky rogue or an intelligent wizard. If we don’t support that kind of class, or make it play radically different than what the player is used to, it can be frustrating. Because this is a nostalgia-driven game, I think it’s important that we meet that expectation.

But in terms of the setting and narrative, we try to make sure that a lot of the quests, plotpoints and issues that your companions have revolve around the same themes. People who have issues with their identity or their relationship with the gods, and thinking about how souls should be used. These plotpoints are all tied together so that you can see that the issues are real, practical and pressing in the world.

RPS: There’s a huge amount of text, even in what I’ve seen today, and the storytelling seems to be more important than necessarily inventing new playstyles. Is it fair to say that a lot of the team’s work has gone into making as many approaches as possible work in the game, both in terms of roleplaying and skillsets?

Sawyer: In the good old days we just kind of wrote dialogue, and added options, and sometimes they were good, sometimes they were bad and sometimes they were meaningless (laughs). Over time, those dialogues got refined and sometimes that was done in ways that were productive and good, eliminating bullshit options, and trash options that were just bad writing or bad places to go.

But with that refinement there was also a very tight streamlining, so in some games it got to the point where everything except the one good and one bad option was lost. That felt wrong to me. I wanted to write dialogue in a way that gives the players a sense that they’re allowed a good range of expression without falling into approaches that are just the expected ones in any given circumstance.

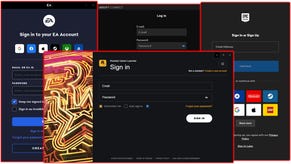

How do we also make those choices feel like they have weight within the context of the game’s systems and mechanics. That’s why we have the reputation systems and why we don’t have a dialogue skill, we trigger things off your attributes, class, background and race. That way we get a broader spectrum of activity. It’s not a question of ‘do you have the speech skill?’, it’s a question of what class are you, what choices have you made?

If you’re in a conversation, Might may be important because you can try to intimidate someone with a show of strength, or you might want to use Dexterity to pick a pocket. Maybe you want to psych someone out by using Resolve, which is kind of a replacement for charisma, but it’s more a case of personal drive and intensity. Or maybe you use Intellect for a logical deduction.

So instead of needing a Speech skill or Charisma for cool dialogue options, we make sure there are plenty for musclebound bruisers as well. It’s not about building ‘The Speech Character’, it’s about letting players create the character they want to play, and making sure that the game has plenty of options and reactivity for that character.

RPS: You mentioned during the presentation that it’s possible to see the dialogue options that your character can’t choose for whatever reason, but that the visibility can also be disabled. Can you turn off the indicators that tell you what the result – reputation-wise – of a choice will be?

Sawyer: Almost anything in the UI can be switched off. You can turn off combat HUD elements. You can even turn on Big Head mode, which I love.

RPS: Does it have its own dialogue options?

Sawyer: (laughs) No. Very early on I said that I’d always wanted to make a game with Big Head Mode, so here it is. But we have a ton of customisability. The HUD can just be portraits, playing entirely with hotkeys.

RPS: I have an instinctive reaction against anything that tells me what an option is going to do, stat-wise. Eventually, that makes me ignore the dialogue and just see the numbers.

What can you tell me about working with Paradox? Do you speak to them often?

Adler: Yeah. They’re helping with marketing and distribution, and QA. Localisation too. They’ve literally given us complete freedom. They give general feedback based on playing the game themselves and having experience with Infinity Engine games, but they’ve literally never told us to change something. It’s very benign.

RPS: Did you know anyone at the company before?

Sawyer: I’m sure Feargus did. Feargus knows everybody. But I hadn’t worked with anyone there before.

RPS: So how did the relationship come about? Did you approach them or did they approach you?

Adler: We approached them. We’d spoken to a few different publishers, looking for help with specifics. We were either going to outsource to a third party, because we can’t do those things ourselves, but we spoke to a few publishers and Paradox happened to be the ones that most closely aligned with what we believe and how we deal with games. And what we think is important.

It was really cool because, as you mentioned (during a break in recording – ed) a lot of their games are quite niche and very hardcore, but Pillars was a good fit for them because it still fits their profile because of its replayability.

RPS: I remember talking to them at Gamescom a couple of years ago and they were talking about some of the projects appearing on Kickstarter, where people would claim ‘we approached every publisher and nobody wants to know about our game’. Someone at Paradox said to me – ‘we want to know!’

Adler: They are one of the only publishers willing to put out a game like this though.

Sawyer: Part of it is being based in Europe, where trends are different and PC is so big.

Adler: A good majority of our fans are European.

Sawyer: Our backers and fans in general. We got a lot of love here. Germany and France in particular.

RPS: Any thoughts on why that might be?

Sawyer: I think it’s a self-perpetuating thing. Whatever elements of culture and markets came together to make certain games popular in certain areas, those things pass down from one generation to the next. In all the time I’ve been in the industry, Germany and France have always been two of the biggest markets for this stuff. Lots of enthusiasts and very detail-orientated fans.

Adler: And Eastern Europe too.

Sawyer: That’s true. For whatever reasons, they really dig our stuff.

RPS: We joked about this earlier, but I do think one of the reasons this kind of game stopped being made is simply because it stopped being made. Take away access it the people who want it – through publishing and retail access – and the ‘market’ vanishes. Digital distribution has changed everything though.

Sawyer: Absolutely. Imagine doing a Kickstarter and every game had to be a boxed copy. There’s no way you can do that.

RPS: Paradox talked to me about their earliest games – the whole team working to box them up and taking a shift shipping them out to customers.

As well as providing developers with access to larger markets, digital distribution encourages people to take risks when buying games. Partly because of pricing but also because it’s a lot easier to drop some money on a game you might have just heard of when you can buy it without moving.

Sawyer: I think the other thing too is to do with how different a Steam sale is to a brick and mortar sale. When a traditional store has a sale they’re trying to clear their shelves of old stock. When Steam has a sale, it doesn’t matter how old that game is, it’s not a clearout.

RPGs tend to have an extremely long lifespan in terms of buying potential. Even when Black Isle collapsed, people were still buying Fallout and Fallout 2 – they still are! There’s this weird thing when we look at sales figures for our products at Interplay. Lots of games have a big spike and then drop off to almost nothing – RPGs have quite a big initial spike but then keep going really strongly for an extremely long time.

Adler: I can’t even tell you the difference between getting a new build out now and in the past. I worked on Neverwinter and getting out patches, testing, was a nightmare. Now, I can move a new build into a folder and essentially run a batch file and deploy that build to everyone.

RPS: There was a fear that digital distribution would encourage people to release software in need of patches. That’s been normalised, hasn't it? We’re moving away from the idea of a finished entity, not just with Early Access but with the expectation of patches and updates.

Sawyer: Even console games have patches but consoles are a real pain in the ass to patch on, in my experience.

One of my favourite games of all times is Darklands and I had to get patch discs mailed to me back then. Darklands was ’92, MicroProse and it was set in historical Germany. You can get it at GoG.

Adler: Everyone at the office talks about it and I had never played it so I downloaded it and...died.

Sawyer: It has a brutal learning curve.

Adler: It was interesting though. I can see where some of the ideas in Eternity came from just seeing a bit of it.

Sawyer: That game originally came on ten 5.25 floppies or eight 3.5 discs. And there were two patch discs after that. You had to write to them, ‘please send me a patch disc, I have included a self-addressed envelope’.

We took the scripted interactions in Pillars almost directly from that. Most of your interactions with the world in Darklands took that form, even exploring towns. But it’s a classless game.

RPS: Is there a goal?

Sawyer: It starts off very open-ended, so you can go out and do whatever you want. It randomly picks a town on this huge map of Greater Germany – I don’t know why they didn’t just call it the Holy Roman Empire because that’s essentially what it was.

RPS: Licensing issues. I think EA owned the rights to the Holy Roman Empire back then.

Sawyer: So from this random town you can just go outside and get smashed by bandits or monsters. There isn’t initially a long goal but they have a neat way of drawing you into it. The plot is about Satan and devil worshippers. There are little villages all over the place and they’re actually randomly generated, and when you go into them sometimes the people are acting weirdly and saying cryptic things.

If you go to confession, the priest tells you to strangle a black cat and say the prayers backwards. That kind of stuff. You can accuse the town of being packed with devil worshippers and if you stay at the inn, they’ll come and try to kill you in the night.

But after you fight them, you’ll find an altar on the hill nearby where they’re trying to summon a demon. If you beat them, they say ‘we’ll have our revenge’ and you get a direction, a city name and a date. The date is always a solstice or an equinox. If you go there on that date, something else is happening and that pulls you into the wider plot. If you miss the date, another devil worshipping village appears, another thread.

So you can be going around doing your own thing but eventually you start thinking, ‘why are these Satan villages all over the place?’ It’s a really neat way of telling a story within an open-ended structure.

RPS: And now I shall play Darklands when I get home. Thanks for your time!