Premature Evaluation: Medieval Engineers

Castle Doctorin'

Each week Marsh Davies punches a hole through the vertiginous walls of Early Access and comes back with any stories he can find and/or watches with grotesque, wet-lipped arousal as the entire structure disassembles in a shower of hot, hot physics. This week, he makes, then mounts, the battlements in Medieval Engineers, a castle construction sandbox. And then he unmakes them, too.

Once you’ve built a castle in Medieval Engineers, you can look at it, hit CTRL-C, then CTRL-V and paste a brick-for-brick duplicate of your entire complex anywhere else in the level. Including the sky - though they are not wont to stay there for very long. Castles, despite a plethora of idiomatic song titles suggesting otherwise, are very much a ground based medium, and when placed in the sky, they attempt to revert to form, with glorious physics-enabled results.

For maximum physics, I recommend dropping one castle on top of another. My PC only manages to render this collision at a speed of a frame every few seconds, but it’s worth the wait. Indeed, I’ve been waiting years: I recall cooing at a supposedly realtime explosive disassembly the better part of a decade ago, but it is only now that such detonations are escaping the ideal operating conditions of tech-demos. The half-measures of Battlefield’s pre-cooked collapses and sly model-switcheroos don’t cut it. I want fully razeable buildings that can be dynamically perforated, chunked and shattered in their entirety. Finally, Medieval Engineers delivers the smithereens we’ve been waiting for, framerates be damned.

Currently there’s not much more to Medieval Engineers than that: you can build a castle, you can build catapults, and then you can use one to smash the other (either way works when you can drop a castle from 1000 ft up). There’s no grander campaign structure in the game, and it’s not clear that this will ever be a particularly directed experience - though multiplayer and an inevitable survival mode are in the works.

It’s natural to fantasise about a future in which you could join a populous server and collectively siege a player-built, player-defended fort, smashing down towers with ballistas or undermining walls, before storming through the breach shrieking “IT’S CLOBBERIN’ TIME!” (Henry V, act III, scene ii). However, I am sceptical as to the feasibility of anything quite on the scale I desire, given the heavy toll the game exerts on even this reasonably high-end PC. Them smithereens ain’t computationally cheap. But that fantasy is coming, rest assured, if not from this game, then another a few years down the line. What Medieval Engineers offers already is a precis - a singleplayer medieval Lego set that you can smash - and that’s been more than enough to devour many hours of my life already.

Those hours have been devoted to the construction and cathartic deconstruction of Fort Titbeard, Mountain Throne Of The Marshlord, Benevolent Ruler of Some Several Acres of Otherwise Empty Sandbox, Inept Mason, Medieval Literature Nerd MA Hons. During this process I’ve learned a number of critical things, usually after the point at which they would have been critically useful:

1) I should have watched the brief tutorial video.

2) I should have disabled autosave.

3) I should have reduced the number of debris chunks to zero.

You can do the last two only before loading a level (select your saved game and hit the “edit settings” button). I recommend doing so because it’s easy to accidentally delete a load-bearing block and watch as your meticulously constructed gate-arch crumples into your meticulously constructed mountain stairway, and rolls downward in a physics-enabled avalanche of pure FUCK straight through all your meticulously constructed checkpoint fortifications, all the way down to the very bloody bottom of the shit-pissing mountain. And then the game autosaves. Gnnnnnggg.

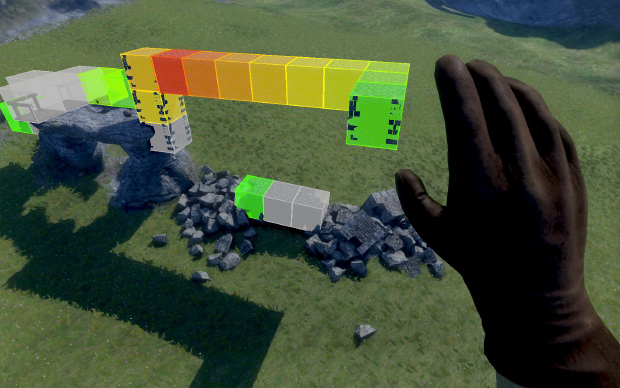

With the chunks reduced to zero, collapsing structures quickly evaporate before they can cause a cascade of misery (and you can turn them on again later, just as easily). Your level thus primed, construction can begin. Left click places the currently selected prefabricated building block, right click erases it. Toggling Z lets you place multiple blocks within the same space and J unhitches you from the rigid grid to which your blocks otherwise snap. I’m not sure it’s all that useful to do this, though, as disregarding grid-snap tends to lead to unstable structures, and I found it impossible to place non-snapping blocks so that they clipped into the ground and offered a solid foundation. Grid-snap, though a little restrictive, nonetheless permits fairly elaborate structures: the integrity of building blocks is generously modeled, allowing you to build out in gravity-defying directions. You can hit N to see the amount of weight each block is bearing, and, as you can see from the experiment below, the game really is pretty forgiving.

Not that Fort Titbeard requires forgiveness, being an edifice built to exacting architectural standards that only falls down three or four times during construction. It consists of a tower rising like a strident peen (as do most towers, I suppose) from the peak of a mountain overlooking the valley. From this a tall thin wall runs along a ridgeway, connecting Proudpeen Tower to a substantial sprawl of buildings and battlements.

Day one goes slowly, as I obsessively lay the foundations and get to grips with some of the less obvious eccentricities of the build menu (all of which are addressed in the short tutorial video I haven’t watched because I’m stupid). Most vital among these things I don’t know is that some blocks conceal a selection of multiple blocks, and you can scroll through their various forms using the mouse-wheel. This makes it a lot easier to construct the corner-pieces for overhanging battlements; previously I’d tried disastrous grid-free repurposing of other block types that resulted in a number of tower-shattering mistakes.

The second day I get distracted from the castle by building a staircase to it. Initially I try manipulating the voxel landscape to create a sloping pathway to the castle gate, but I find it hard to do this smoothly and exactly; for some reason the way the voxel brush hangs in front of the camera makes it impossible to judge distance. Instead, I decide to build a very elaborate zig-zagging staircase, punctuated by fortified waystations, all the way up the mountain. The incline doesn’t really demand a zig-zag, but grid-snap, alas, does. Without gridsnap, the staircase block refuses to be embedded into the mountain side, making a more direct, diagonal ascent impossible. It looks cool, mind you - not unlike the approaches to Japanese castles, with their many switchbacks, chokepoints and defensive overlooks. And then I send an avalanche of bricks down it and fuck the entire thing up.

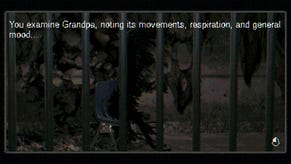

Day three and, having dechunked my level settings and repaired my staircase, I’m back on the castle proper, building out the fort at the back, and adding enough rooms to house a reasonable contingent of men. Not that the castle will, because this is singleplayer. And I’m going to smash it to bits. To whit, once complete, I spend a few satisfied minutes wandering round the battlements of my creation before spawning a horde of barbarians in the valley below and setting them to reduce Fort Titbeard to ruins. The barbarian bots are very much in the prototype stage, however, and run off into the woodland, bellowing like idiots. Clearly, the task falls to me.

In this freeform mode of the game, the player can summon and instantly fire boulders, holding the right mouse button to charge up their force. I zip around the fort, knocking chunks of masonry out of its most sensitive points, obliterating its outer defences, carving the barracks in two and doing something terrible to poor Proudpeen Tower. I spawn a few barbarians in the castle courtyard, but they just run into walls yelling, so I pummel them with boulders, too. Finally, as the cries and crumbling masonry fall silent, it’s time for the drop: a cut and paste later and Fort Titbeard is being annihilated by its evil flying twin. I’ve set the number of chunks midway to 500 - I daren’t melt my computer with any more - but this is not nearly enough to render the collapse of two mighty Titbeards. Instead, the chunk limit gives the effect of the forts boiling away from the landscape; towers tumble and then evaporate. It’s strangely beautiful.

I’m not sure how many times I will be inclined to rebuild and raze Titbeard, or other castles like it. The novelty of the construction set and its physics will wear off, and it remains to be seen whether multiplayer will be able to pull off warfare on a scale to make sense of castle architecture. Of course, I haven’t yet explored the building of catapults: the game has components enough to build elaborate mechanisms and no doubt the community are already using these to create ingenious and often NSFW contraptions of the sort we have seen in similar ballista-building-game Besiege. Full-scale online siege warfare or not, the prospect of smashing Titbeard’s doors in with a giant flaming dingdong may prove to be well worth the price of entry.

Medieval Engineers is available from Steam for £15, though this price will rise as the game adds more features. I played version 0.02 on 25/02/2015.