What Civ VI Could Learn From Civilization: Call To Power

Excavating the forgotten Civilization game

I’m not entirely sure what’s going on. I’m playing Civilization: Call to Power, and at some point the world turned from relative Civ familiarity (with shoddier mechanics) into a Twilight Zone where everything is just… wrong. I think things started getting strange when my still ancient-looking capital city of Rome circa 1700AD started being showered with little animations of paper, crippling the city’s production. Sending a spy to investigate, I uncovered that a man in a blue suit (all the rage in 1600s Thailand, apparently) was behind it all - a scummer lawyer catapulting bloody injunctions.

What in Sid’s name is going on?

Civilization: Call to Power and its sequel are baffling, yet also fascinating - they’re the shameful secrets of the esteemed 4X series that Sid Meier and Firaxis had no involvement with, borne of huge ambitions, an inexperienced dev team at Activision, and (fittingly, given the stifling, all-pervasive role of lawyers in the game), a lawsuit.

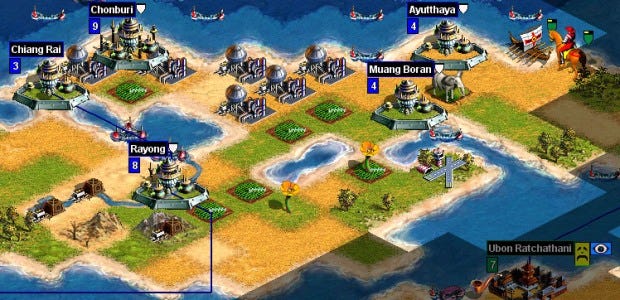

The best part of a millennium later in my Call To Power game, the political dynamics of the world bear no resemblance to reality; in fact, they don’t even bear a resemblance to the dynamics of any of the other Civilization games. I’m tied up in a endless shadow war with my neighbours; lawyers suing other Civs over who knows what; advertising blimps are beaming discontentment onto rival populations; and once-great cities are turning into barbarian dens of iniquity at the callous click of a spy’s fingers.

Hang on. There was a city there a moment ago, wasn't there? There was definitely a city there but now it’s been replaced by a forest. Must’ve been that crusty bastard Eco-Ranger (best described as a Hippy Hovercraft - complete with a peace symbol) that was loitering around, capable of returning a city to nature - i.e. decimating it - in an instant...

At the click of a mouse button, I zoom out to orbit, where the most developed nations are building space colonies while the weaker nations are still prodding each other with pikes and the oceans - overflowing due to global warming - are filled with sea cities. It’s chaos, so vast and shambolic that I struggle to immerse myself in that classic Civ fantasy of guiding a nation through history. The surreal history that’s rolled out on my screen is just too far removed from any that I recognise from reality or fiction.

In 1997, the Civilization series was in jeopardy, despite the roaring success of Civilization II the previous year. Spectrum Holobyte, the company that owned Sid Meier and Bill Stealey’s MicroProse since 1993, laid off most of the staff at MicroProse and consolidated the company. Stealey had already sold his share and scarpered in 1994, but this move was the final straw for lead Civ designers Sid Meier, Jeff Briggs and Brian Reynolds. They left and went on to found Firaxis Games.

The Civilization brand remained with MicroProse, though this was called into question by Activision, who in 1997 bought the rights to the Civilization brand from Avalon-Hill, which was responsible for distributing the original Civilization board game outside Europe. Subsequently, Activision and Avalon-Hill sued MicroProse for trademark infringement, so MicroProse went one better by buying out Hartland Trefoil, the original creators of the Civilization board game and true owners of the license. MicroProse successfully counter-sued, leaving Avalon-Hill to pay compensation, and Activision with the rights to create a single game under the Civilization brand (presumably because MicroProse was in dire straits financially, bereft of Sid Meier and co, and had no intention of making another Civ game itself).

That game was Civilization: Call to Power, and having sprung into existence in that environment, it's no wonder that upon its release in 1999 it turned out a little… odd.

Not that you would necessarily sniff out anything wrong when you first jump into Call to Power. It looks pretty enough, with a deep colour palette compared to the then three-year-old Civilization II, and decent animations. It sounds wonderful too, with a meditative soundtrack spanning from soothing Gregorian beats, to haunting Arabian melodies, onto chilled liquid-y tracks in later eras that have that nostalgic quality of sounding like what everyone in the 90s imagined ‘The Future’ would sound like.

The first notable variable in Call to Power is the lack of workers, who have been replaced by a Public Works tax. You decide what proportion of your empire’s production you want to dedicate to Public Works projects like mines, farms and fishing nets, as well as more tactical structures like watchtowers and airbases later on. It’s a strange feeling in a Civ game to plonk down improvements with your own godly hand instead of ordering a unit to do it; an uncanny touch of the base-building strategy game in something altogether different, but you can see why it’d appeal in the days of non-automated workers, who felt fiddly to have to keep your eye on all the time.

As you progress however, you soon get the feeling that the game is rushing you through the early eras of the world - the ancient, classical and medieval - so that it can show you the crazy shit it has in store later on. ‘Who cares about bloody horses and spearmen and rickety chariots clip-clopping along dirt roads and uncharted lands?’ it seems to say. ‘You’ve seen all that crap before, haven’t you?’. Then when you’re about to say that actually that exploration and steady progress is part of what makes Civ so moreish, it interrupts with a vision of the modern world you’ve never seen before.

The Call to Power timeline goes up to the year 3000, making much of the early game feel hurried and unexceptional where normally it’s the best bit. There’s little in the early eras of Call to Power that’s new or done better than Civ II, and the lack of colourful advisors, city views, throne rooms to gussy up, and interesting diplomacy make it lack the vibrant personality of its siblings. One new feature that does work well, however, is slavery.

Early in the game you get introduced to the slaver unit; unfortunately, my first encounter with the bald, burly bastards was through an animated net being cast over my capital, Rome, and a portion of my population being swept away to work as slaves in distant lands. Aside from stealing population from cities to use as cheap labour, these guys can also enslave enemy units when you win battles, converting them to labour in the nearest city. One of my few noteworthy acts through the early years of my game was to create a villainous slave economy, running on captured barbarian soldiers (just-deserts for tormenting my populace for millennia) and innocent civilians plucked from Thai cities (I have no justification for that one).

I probably should have read the signs by the 1700s, when abolitionists began stealing my slaves and reinstating them as civilians in distant lands, that the good times of free labour for all Rome were coming to an end. The end of slavery came swiftly and brutally, as none other than my good Thai neighbours passed the Emancipation Act, which collapsed my slave economy in an instant, wiping much of my labour force and leaving me to contend with riots across the entire nation.

Despite getting what was coming to me, I respect the slavery system, which presents you with a monumental game-defining gamble of the sort you just don’t see in more recent Civilization games; Civ IV had Slavery as an early civic, though all it did was allow you to sacrifice population for production. In other games in the series, your path towards progress - be it slow or quick - isn’t jeopardised by anything other than a military invasion. In Call to Power, slavery is as close as Civ has ever got to some kind of global economy, where a shift in the status quo can send the whole system into disarray, seriously damaging dominant nations in the old world and making it easier for new, more progressive nations to rise up. It’s a bold mechanic, and one that would be welcome in Civ today.

The modern and near-future world of Call to Power isn’t a pleasant place to be. Where the main series feels celebratory in tone and tries to capture the world in all its eccentricity, Call to Power sardonically sets its sights on western society in all its madness. Even if there is peace on the surface, the world is kept in a state of perpetual misery and instability thanks to the following motley crew of units:

These smug Patrick Bateman types, leaning back in their swivel chairs with their feet on the desk, sliding across landscapes to establish corporate branches at rival cities to siphon their production back to your Civ. Their soulless shouts of “Who needs minimum wage?” makes them instantly dislikeable, and makes me feel like a bastard for using them. But hey, such is the nature of the world in CtP, so I’ve no choice but to play along.

The successors to Corporate Branches are Subneural Ads - those steampunky blimps I mentioned earlier - which beam advertising down onto cities, triggering instant unhappiness, and an animation of a disturbing blabbing sprite-face, presumably touting products that the target city can never obtain.

My favourites are the terrifying TV-headed televangelists, who yell “Prrrrray for Mercy” before gliding through the air - their legs trailing behind them in spectral fashion - and attacking cities with prophecies of biblical armageddon.

Through these and other cynical, oddly anti-establishment units, Call to Power feels like it’s making a (very heavy-handed) statement about the modern western world - “Look at how corrupt and mad we’ve all become”.

Global warming is inevitable in Call to Power. Rival civilizations are more than happy to sign up to eco-pacts (presumably because they sound so PR-friendly), but as soon as oil refineries become an option (i.e. as soon as pollution actually becomes an issue), everyone jumps onboard. Not that this is a game with an environmental conscience, because eventually you can just build underwater cities, negating many of the problems caused by diminishing landmasses.

Just as the callous units and mess of the modern world in Call to Power begin to make me feel despondent, my discovery of Space Flight unlocks a new layer of map over the original one, allowing me to toggle between Earth and Space views. My first thought is that maybe I can enslave some alien species. It’s certainly not beyond the volatile realm of this game’s imagination. ‘Alien Archeology’ is indeed a late-game technology (leading onto the ‘Alien Life Project’ science victory, whereby you send a probe into a wormhole and build an alien life lab to attain Call to Power's answer to the archaic old Space Race victory). Alas, alien contact is very much the endgame, and my dreams of a second era of free labour for Rome are dashed.

Instead, you can colonise orbit, which increases production and food in cities on Earth, and lets you take units into space, dropping them anywhere in the world. None of it’s really as exciting as it sounds, though you have to respect the ambition in depicting not only a twisted take on human history, but a vision of the future as well - however ill-considered.

Call to Power is fascinating because amidst all the chaos and lack of clear direction and identity, it’s filled with nuggets of ideas that run deeper than anything the main series has offered up in years. More than just making a statement, it’s making a million mini-statements at once, all drowning each other out in a ludicrous Babel of a game that can hardly be called ‘good’, but is kind of brilliant.

Call to Power does away with its siblings’ welcoming personality, dropping the beloved City Views of previous games, cutting down on diplomacy, and slapping in bizarre, low-bit photos of leaders that look nothing like how we imagine (check out old ‘Ramses’ below). Yet none of these things really matter when the world is an eclectic circus of bizarre bureaucracy, absurd units, and strange technologies that seem to have emerged straight out of a teenage Terry Gilliam’s unprocessed nightmares.

Possibly in an attempt to eradicate our memory of Call to Power ever having happened, Activision released Call to Power 2 the following year, stripped of the prestigious ‘Civilization’ in its title. The game was a big improvement technically, with better controls, AI automation, and diplomacy that was actually worth engaging in. It maintained much of the madness of its unloved predecessor - the televangelists and the highly speculative future technologies - while paring back on unnecessary bloat like space colonisation. While it doesn’t have that same bonkers intrigue of the original, it’s certainly a more accomplished game and the best way to experience the strange world of Activision’s imagining. You can buy it at GOG.com, and there’s an excellent unofficial patch at Apolyton.net that sorts out some of its plentiful bugs.

Among its many failings, Call to Power overstretched itself by attempting to create not only an alternative human history, but also a future - two fantasies so vast and complex in themselves that they’re best off being kept separate so that each one can be explored fully. The main Civ series and Alpha Centauri attest to that.

And yet.

And yet, and yet, and yet... there is some spaghetti you can peel off the figurative wall at Activision’s offices circa 1999, and wonder whether there are some ingredients that could be used in the increasingly welcoming and personable Civs of today. Call to Power attempted to dig deeper into the systems and idiosyncrasies of human history; for the most part it failed, but by introducing promising systems like slavery and corporations, it showed that there is plenty left for the series to explore. It’s wonderful that Civilization 6 is set to be prettier, less cluttered and filled with more wonderfully eccentric historic personalities than ever, but there is some wisdom to be found in the shunned Call to Power Civilopedia, and perhaps it’s time for Firaxis to look into it.