'Wilmot's Warehouse is a language game', please discuss

Wilmot and Wittgenstein, sitting in a tree

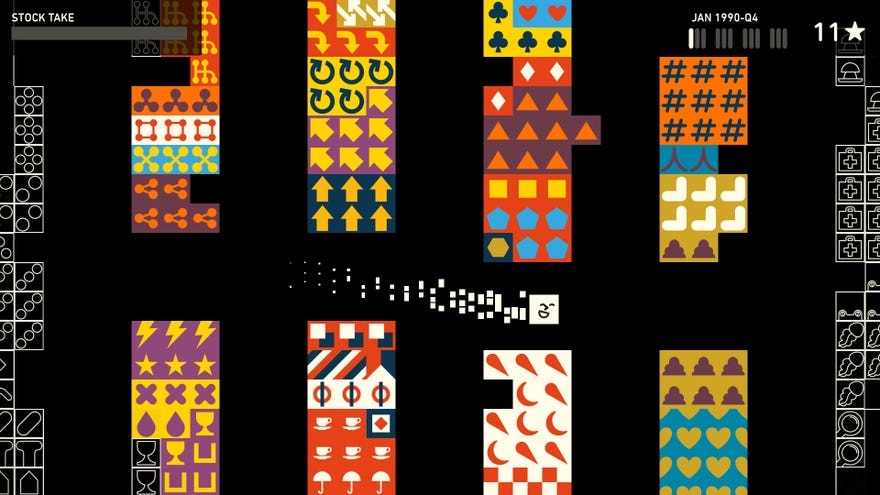

I don't think we ever see the extent of Wilmot's horror. He's a square in charge of a warehouse, single-handedly responsible for storing and serving up hundreds of amorphous objects. We, the player, only see those objects from the top-down, a step removed from the abject terror of categorising off-colour melon slices that simultaneously resemble 50% of an egg. Maybe reality is less blurry from his perspective, but I doubt it. Wilmot's Warehouse is a world of raw pictorial language, and an ingenious platform to explore how language works in our own world.

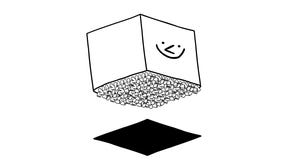

Let's start with this, whatever it is. (Sorry for the atrocious quality, my screenshots are trapped on my Switch and for convoluted reasons taking a photo was the only way to free them.)

I might decide that's a fireman's pole, and so should be stored next to my other 'dangerous' items like boxing gloves and archery targets. Or I might cheekily ignore the pole, pretend it's an abstract representation of a black hole's event horizon, and stick it with my space crap. Accuracy is unachievable and irrelevant. All that matters is I remember whatever semi-sensical decision I go with, and can hoof it back to wherever I store it in time to avoid disappointing a customer. I'm free to classify according to my whims - or so it seems.

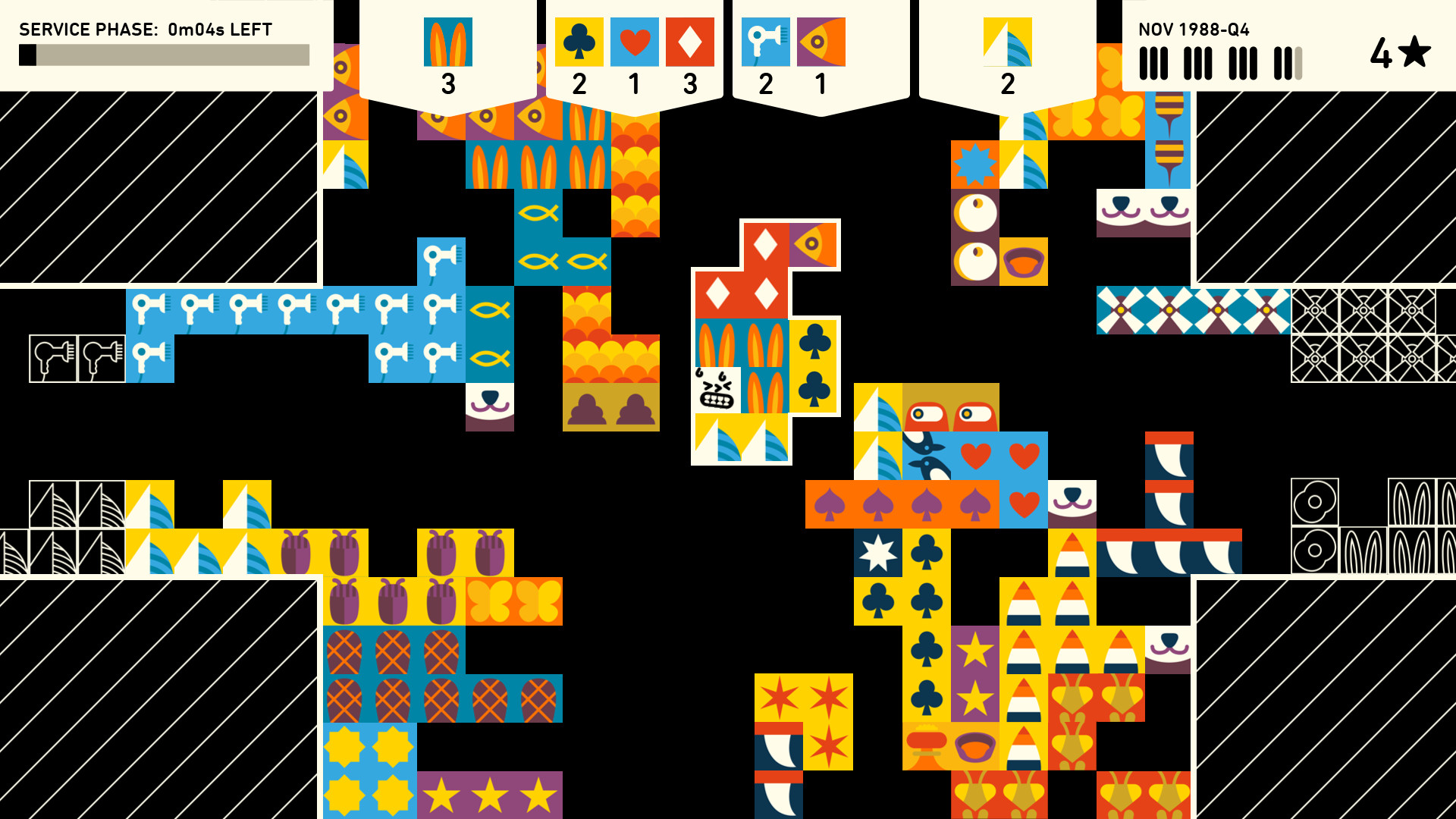

Occasionally a customer rudely shatters my meaning with their own. They'll ask for multiple related objects at once, like two beaks and a camel. Before I got that particular order, I thought those beaks were boats. But now I know that if I want to make future deliveries on time, I'll need to store them with my animals. The customer is always right.

Ludwig Wittgenstein would have loved Wilmot. He was an Austrian philosopher, famous for writing a book about how every other philosopher doesn't understand how language works. We can't moor most concepts to immutable truths, says Wittgenstein. Nothing can be anything without context, and he gets at that by talking about games.

Take a moment to try to define the word 'game'. Go on, I'll be waiting for you after this disorganised mess.

If you’ve come up with a definition that seems to work, you've probably lumped games in with conceptually different activities like reading books or watching TV. A definition seems impossible, but we all pretty much agree on what a game is. Different games are united by common traits, even if there is no one trait that applies to them all. They share, as Wittgenstein puts it, a family resemblance.

Wilmot strikes me as a delightful representation of that idea, especially because it reflects the way Wittgenstein liked to explain what on earth he was talking about by approaching ideas from multiple directions.

I put my primroses near my oven mitts, largely because I've let the introduction of seeds and something that might be an onion blur the distinction between flowers and food. I can't say exactly what unites them, because exactness doesn't apply. 'Exactness' only exists up to a point, expressed by a customer ordering two related objects. Accuracy will always be relevant, because a defining part of language is the possibility of using it incorrectly. We can't define a game, but we can still point to a sock as an example and be wrong.

In retrospect, that pole-thing is obviously a game of golf.