Deus Ex at 20: The oral history of a pivotal PC game

From studio conflict to creating a classic

Deus Ex is the king of the immersive sims - the blueprint from which an entire genre of ideas has been pilfered. If you’ve loved a Dishonored game, you’ve enjoyed Deus Ex by proxy; its design, and even some of its developers, can be found at the very centre of Arkane’s DNA.

For those who played it 20 years ago, Deus Ex set expectations for how malleable game worlds could be, and new standards for reactivity that the rest of the industry failed to match in the decade that followed. Deus Ex was ultimately so influential that, as one of our interviewees points out, its innovations now seem normal.

Here’s the story of how it was made, as told by the people who made it. The story begins in 1997, at a time when testosterone-fuelled first-person shooters still dominate PC gaming. Thief and System Shock developer Looking Glass has closed its Austin studio to save the ailing company, leaving Warren Spector and a team of crack simulation nerds without a project.

Origins

A group of unemployed Austin developers busied themselves with prototypes and experiments. But rescue was coming, in the form of Doom designer John Romero.

Steve Powers, level designer: When Looking Glass Austin closed, the team stuck around because the rent was paid on the office. We’d come in during the day and work for free, pitching ideas and building things. One of the concepts that came out of that was a spy game called Shooter. It was going to star a James Bond-type technical spy who could hack devices. Warren floated this idea of nanobots; an agent who could control nanotechnology. It was really crude - it never really went further than a few little mock-ups, some sketches and documents. Then one day John Romero showed up in a giant yellow humvee and said, ‘Hey, we wanna make a studio here. What have you got?’.

John Romero, Ion Storm co-founder: It was, I believe, September of ‘97. One of my artists had just heard that a Warren Spector project had been cancelled. I came down to the Looking Glass studio in Austin and pitched him on the idea of joining Ion Storm. I was trying to line up several games in different genres. I also tried to get Tim Schafer in to do adventure, but he was too cozy at LucasArts. He didn’t wanna leave yet.

Ian Livingstone, executive chairman of publisher Eidos: We’d become quite reliant on Tomb Raider, and were looking to widen the portfolio. We had already established Ion Storm to enable John Romero’s Daikatana and Tom Hall’s Anachronox to come out. For one reason or another, they weren’t meeting expectations. I knew Warren from when he was working at Steve Jackson Games in the pen and paper RPG days. I knew what a great designer he was. We decided to back the idea.

Romero: Warren had done really great stuff at Origin, and seemed like a really balanced person. He doesn’t have an ego, and he didn’t make failures. I knew I could count on him. I said, ‘You can make any game you want, you can take as long as you want, and money’s not an issue’.

Livingstone: Warren wanted to expand on System Shock and what he could do in roleplaying, introducing stealth and first-person shooter elements and other ways of getting through. It ticked all the boxes for me. My only worry was that it wouldn’t have a wide enough audience.

Romero: I said, ‘Just run the studio, we’ll pay the bills and keep you isolated from anything that’s happening up here in Dallas’.

Sheldon Pacotti, lead writer: It was maybe 20 people. There was publisher oversight, but it wasn’t heavy-handed.

Livingstone: We gave them total autonomy. The Dallas team was busy enough developing its own games.

Romero: We let Warren keep his team and find a new office space that was bigger, because the team was going to need to get bigger. These people had worked on Thief: The Dark Project.

Austin Grossman, writer: Deus Ex came pretty directly out of a learning curve that had started at Looking Glass with Ultima Underworld, System Shock and Thief, before they had phrases like emergent gameplay and ludonarrative dissonance. We didn’t have any vocabulary for it, but we would have intensive discussions about what worked and what didn’t.

A political awakening

A series of key hires saw Deus Ex, and many of its young developers, find their voice.

Romero: The ideas started to really gel after Warren hired Harvey Smith.

Harvey Smith, lead level designer: I was exchanging emails with Warren, and as soon as he started talking about a first-person shooter RPG with spy fiction background stuff, I just wrote a mission description. It ended up not being used in the game - it was all about surveillance from one side of a hotel, across a courtyard to a room on the other side, planting information, blackmailing, and sniping. He convinced me to move back from California to Austin.

Grossman: The key note that I remember is ‘All conspiracy theories are true’.

Robin Todd, writer: We were reading all these different conspiracy books, about the gold and silver standards, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail.

Smith: I remember seeing some pitch documents lying around, and there was one where the protagonist was the last descendant of Jesus Christ or something. JC.

Powers: Right before the new millennium, secret societies were all the rage.

Smith: We were very influenced by three games: Thief, System Shock 2 and Half-Life. There was a lot of discussion around whether it was more elegant to get through a level without being spotted and killing everybody. But there was also political discussion about whether there was inherent bias in a game that gives you a mission to kill a bunch of enemies without questioning it. And of course, there is.

Grossman: Most of the political thinking came out of conversations between Warren and Sheldon.

Sheldon Pacotti, lead writer: I was a programmer. I didn’t find out until 30 minutes into the interview that they were interviewing for a writer. I saw Warren grab a basketball in the UNATCO headquarters and throw it down the hallway. They were trying to build a real place, with real people. I was excited about building all that logic out, and making the game fully reactive to whatever you do.

Smith: Sheldon came in halfway through the project and rewrote it in this voice that I’m not sure anyone else would have been capable of.

Pacotti: I’ve always been a very political writer. I’m attracted to social change and revolutions. If you see allusions to Foucault in there, that probably came from me.

Smith: We would say things like, ‘In order for one person to be a billionaire, millions of people have to live in poverty’. And then Sheldon could come in and back it all up with deep historical examples.

Todd: It wasn’t this thesis statement from the outset. Sheldon was really into the conspiracy and socialist angle, I enjoyed a lot of cyberpunk at the time, and Austin was very much into politics.

Smith: Warren would contribute ideas here and there that I will always remember, like ‘You can’t fight ideas with bullets’.

Pacotti: I was certainly pilfering from Warren’s library - a lot of books about the NSA and the US government, different conspiracy theories. It was something he’d been into for a long time.

Smith: My dad was a welder, my mom was 15 when I was born, I graduated high school without knowing the difference between the left and the right politically. I don’t think I’d ever heard anyone say ‘The people you call terrorists are freedom fighters to someone else’ before. That period of time from ‘97 on was a political awakening for me, partly because of all the arguments we had and the research we did.

Player liberty or death

Ion Storm Austin committed to making its levels open-ended playgrounds, and embraced the resultant complications.

Todd: Liberty Island was the vertical slice and the proof of concept. The designers would leave datacubes and newspapers around the levels, and the writers would come and fill that out.

Powers: I remember placing a security guard with a sack lunch on his desk and a note from his kid. ‘Hope you enjoy your PB & J, I made it myself. See you tonight’. Players would execute the guy, see this note and reload.

Smith: Doug Church helped with a bunch of AI stuff. We concluded that it doesn’t make it a better game that enemies run away from you, but it makes it more interesting. You have to make the decision to shoot them in the back just to feel complete, or let them get away.

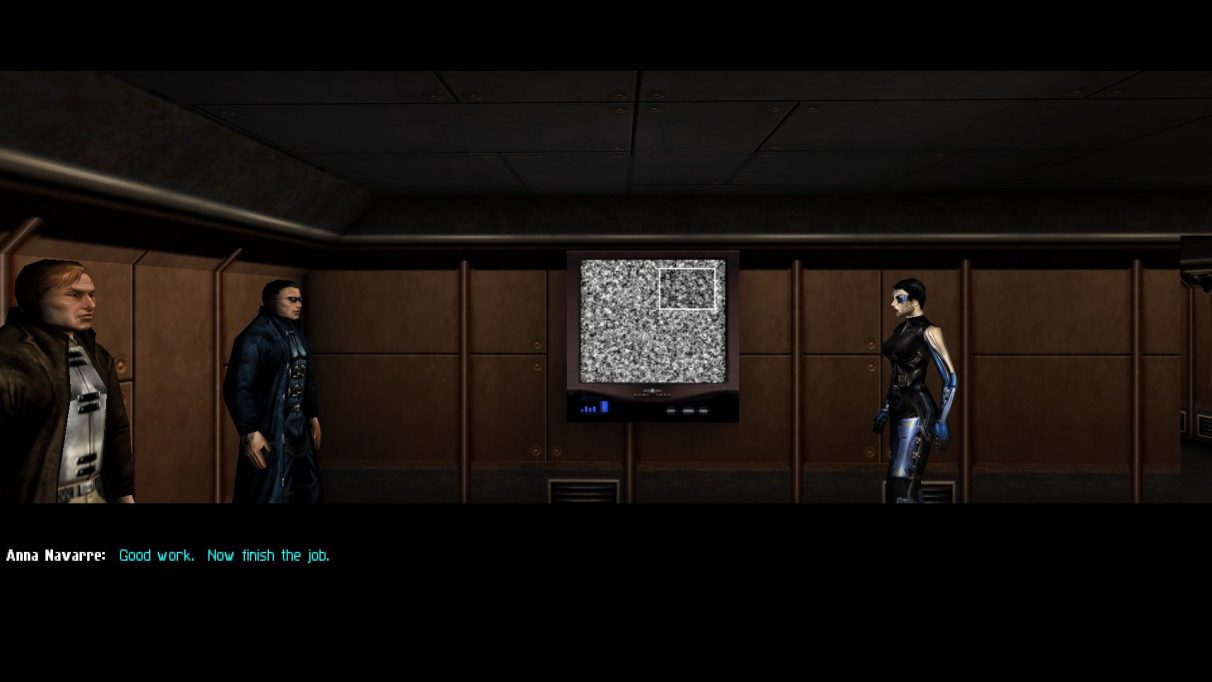

Grossman: One of my favourite moments in gaming is the stand-off on the plane with Anna Navarre, where she’s telling you to kill the guy. And you realise you don’t have to. You’re holding this gun in your hand, and you can shoot anyone in the room, and the plot handles it. That opened up my understanding of what a game narrative could be. It’s a lovely moment professionally, when you realise people are doing something new, and suddenly the medium looks bigger than you thought.

Livingstone: Early on, there was a buzz coming from the studio. There was a lot of excitement and chatter and happy-looking people wandering around.

Romero: I thought it was a really great weaving of shooter and RPG with multiple paths through it. It was like 9,000 lines of dialogue.

Pacotti: You weren’t paying $20,000 for every line of dialogue in those days.

Grossman: Harvey got in touch and said, ‘We have two writers, but we have more writing than we can handle, so do you wanna write?’”

Pacotti: I inherited a story bible that had pages for 100 different characters. Maybe about half of them made it into the game.

Grossman: I was looking through the script, and it’s a lot funnier than I remember. It was such an absurd world that if we played it straight the entire way, I don’t think that would have worked.

Pacotti: I worked really hard on capturing the different ways every character speaks, where there’s gang stuff going on, just trying to get all of that right.

Grossman: I cringe at a lot of the faux-urban characters, the pimp stereotypes and Chinese gangsters. That’s a thing you could never do now and should not have been done even then.

Pacotti: I would give a lot of thought to the mental life and rationale of all the characters and groups.

Grossman: JC Denton had to be a bit of a blank because the player is making decisions on his behalf. Is he a tough guy? Is he funny? He has a kind of ironic tone. I never really understood what was going on in his head. The character I enjoyed the most was your brother, Paul. You were on this path of figuring things out, and he was just ahead of you.

Pacotti: Harvey took all the story home with him and came back with a draft. He had a big input on that final, tight storyline. Credit for the dialogue tool has to go to Al Yarusso. I remember the engineers saying they wished they had time to develop something more sophisticated, but in practice it was very versatile and powerful. Simultaneous coding and writing let us give players great freedom, rather than forcing mission outcomes or a linear series of gates.

Grossman: An individual level had a lot of space in it that you could stick around and explore, or you could go straight through. We called it the string of pearls structure. It was explicitly designed that way, with the expectation that plenty of players would miss whole chunks of it.

Romero: I love the way that you decide where you’re gonna go and how you’re gonna do it.

Pacotti: We had a fallback for all these cases where you could kill a character early - a datacube on the ground that would trigger your mission.

Grossman: A top level motto was that every single task had three ways to accomplish it.

Pacotti: To this day, I hate boss battles. You go into a room and then all the doors shut, it just feels so artificial.

Smith: It was like D&D with guns. It was very powerful to not be constrained in that way.

Grossman: They poured a whole bunch of different game systems into it, and then frantically tried to tune and correct and manage it. Which was exciting, but it led to a lot of uncertainty.

Pacotti: One time in VersaLife [] a test player spooked a guard dog, who upset a secretary, who may have defended herself with a knife, which then drew employees and guards from across the facility into a battle royale in one of the elevators.

Grossman: When you have a lot of interacting systems, you’re constantly finding exploits. You could attach laser tripwires to the wall in a stepwise sequence, and stand on each of them, working your way up a wall, which I don’t think anyone had ever seen or particularly wanted.

Faction warfare

During development, Ion Storm Austin was in conflict, both internally and with the Ion Storm team working on Daikatana in Dallas.

Smith: There were two distinct subcultures inside the level design movement, and they were at times hostile to each other.

Pacotti: There was a Design Team A and a Design Team 1, hired in different ways. It became trench warfare between those two. One was the fantasy group, and one was the realism group. One wanted to build the world to support game navigation, and the other wanted to build to the actual proportions of what a bar or street would be.

Smith: I wouldn’t say one was realism and one was fantasy. More that our team was Looking Glass fans, and the other was more RPG-oriented. We were working with some daft subject matter, but we took it seriously. The other team liked easter eggs and in-jokes.

Grossman: Even in the late stages there were tons of debates about how it was supposed to work. It was a big clash of philosophies and backgrounds with the system-driven people and the Origin RPG people.

Romero: Warren would have the dev team work on different things that would be in conflict with each other. One of them was gonna win. He would let that go on, and choose the best solution with the team. He would be fair about it.

Pacotti: Eventually the fantasy group won out. I can’t remember if that was A or 1, but that’s how the direction of the game went. There were hard feelings on both sides, but honestly I think that’s what makes the game work. There’s this strong tension between the real and the imaginary. That’s what a conspiracy theory is.

Smith: We’ve lovingly ribbed Warren for not wanting to make a difficult decision around all of that.

Ricardo Bare, level designer: The double design team thing is ironic given that the game’s most memorable moments are about putting the player in crisis points where you have to make a decision.

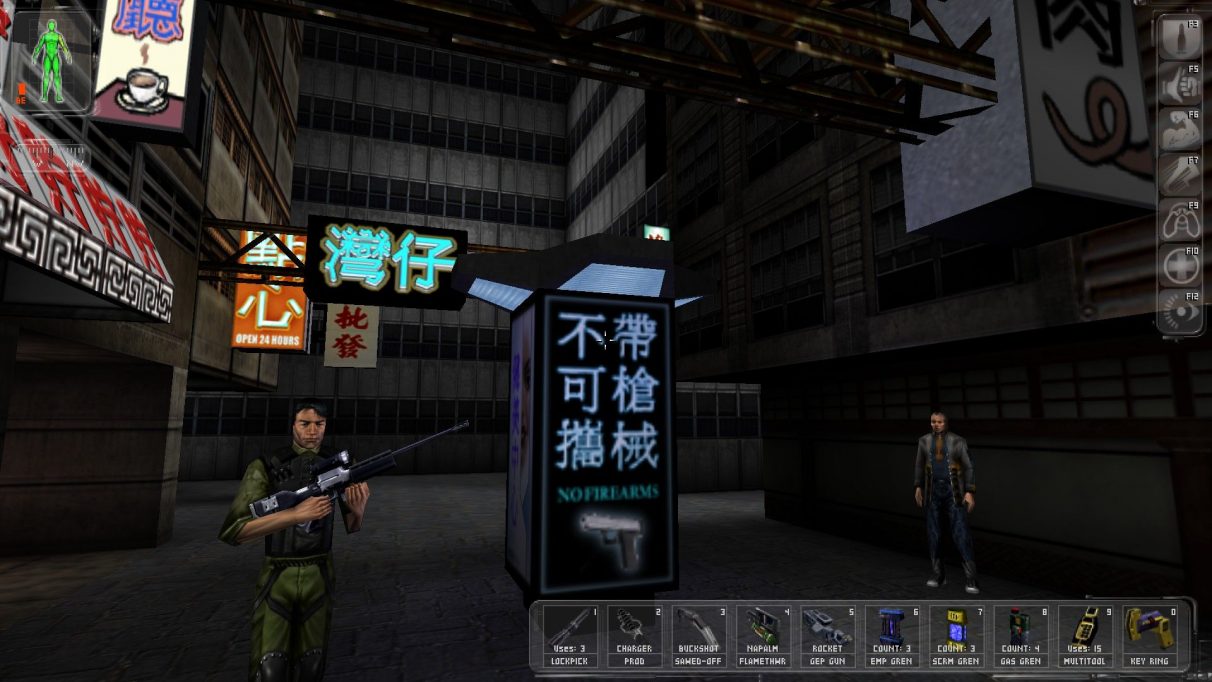

Pacotti: A lot of the developers had come out of working on sprawling 2D tile-based adventure games at Origin. The mental model was, ‘I’m just gonna start building stuff and dreaming of things’. That’s how Steve Powers approached the Hong Kong map.

Grossman: Since the levels were being built independently, I had to go in and forge relationships with each different designer and understand their approach.

Pacotti: At the end of the UNATCO segment, you fight Majestic 12, get on a helicopter and fly off to freedom. And then in the next mission, you’re loading into the basement of a Majestic 12 facility. You’re right back where you just escaped from, essentially, and for a long time I struggled with how to open that. Then Austin wrote this first line where Jock the pilot says, ‘I blew it, JC.’

Grossman: It was so complicated and it still feels a little unbelievable that it all hung together.

Pacotti: A lot of locations and missions got cut as we tried to make the date. I wrote dialogue for rescuing people who had been taken out to a pirate island. There was a White House mission that seemed pretty pivotal at the time. The president was a puppet of the Illuminati - he’d been replaced with a clone, and you rescued his daughter.

Bare: Deus Ex was my very first job in the industry. I came on the project for the last year and a half, and Harvey pretty much dumped a bunch of levels into my lap. They were at varying stages of maturity. I had a huge amount of freedom.

Smith: There were very few check-ins. Eidos was over in the UK. Those guys would fly in for an important quarterly check on how the money was being spent, and party so hard with the Ion Storm Dallas guys that they would inevitably email us and go, ‘We’re gonna make it down to Austin next time’. Therefore we were allowed to make our crazy, crazy game.

Romero: One of my co-founders, Todd Porter, wasn’t making a game anymore. So he was just doing whatever he wanted to do, which was getting involved in Deus Ex. He tried to shut down Deus Ex probably two to four times - just get it cancelled.

We had a real long meeting, and I remember telling him - I don’t care what you’re hearing down in Austin, whatever Warren makes is great. I don’t care how he does it, if they’re having a circus every day in the office. So we’re leaving them alone and we’re not cancelling the project ever.

Todd Porter, Ion Storm co-founder: I never tried to cancel any projects nor would I have had the power to do so. I really had very little interaction with Warren and left Ion long before Deus Ex shipped.

[John Romero strongly stands behind his statements regarding Todd Porter’s involvement.]

Romero: It wasn’t really an expensive game to make. I think it was similar to Daikatana. It had about the same number of people, and Warren didn’t have to restart his whole game like I did.

Pacotti: In Dallas there was this churn - they were changing engines so many times. Stuff was behind and not crystallising creatively. There was a sense with the relationship with the publisher that we were the good branch of Ion Storm.

Smith: Ion Storm Dallas was a crazy place. It’s not like they were the parents in the room.

Romero: The Austin team were mad that we were giving Ion Storm a bad name. They were obviously not happy with anything they heard coming out of Dallas. They even went and created a new logo, and they wanted to rename the studio. Warren let them go through that whole exercise, but eventually didn’t change it. I totally understood.

Smith: In Austin, our culture was much more nerdy and reserved. This sounds evil, but it was more thoughtful. Meanwhile, up in Dallas, you had this wild party culture that was much more aggressive and spun out of the shooter scene. We were just cats and dogs.

Powers: The public face of the Dallas office blended well with their demographic. But we were aiming at a different audience, and that same vibe would have sent our players looking elsewhere.

Crunch time

As Deus Ex’s potential became clear, staff leaned into the project, sacrificing their own health in the process.

Smith: We were not particularly awesomely paid, and we worked our asses off.

Pacotti: I opted into a total crunch from the moment I joined Ion Storm, simply because I saw the creative potential of the project. Later, Warren and Harvey had to talk sense to me.

Bare: That was in the days when people considered it a badge of honour to work themselves to death, which was super foolish.

Pacotti: I knew Deus Ex would be more momentous than any of the fiction I was working on, so I set everything aside and wrote for the game at work, at lunch, at home, and on the weekends. In a mature company, today, that kind of schedule would be seen as exploitative.

Grossman: Liberty Island was the last level to come together. The stakes of it were really high, because that’s where we educate you about what Deus Ex is. That was what we were anxious about.

Pacotti: Everybody was starting to realise it was going to be something pretty special, and the battles did get very intense at times. Warren was asking for a little more time with the publisher. He said, ‘I told them, if you just give us three more months, I’ll give you the game of the year’. They didn’t give us three more months. It could have been tighter, we could have made it even better.

Livingstone: Ion Storm had a bit of a problem delivering to an agreed schedule and budget.

Truth will out

Deus Ex was released in 2000 after years of toil, but its creators had little idea of how it would be received.

Romero: Warren thought of the marketing campaign with a UNATCO website. People thought it was a real government organisation. It was an ARG kind of situation.

Smith: The deeper you read into that website the more we started using questionable coded phrases that were adjacent to fascism.

Powers: It had a fake sign-up process if you wanted to be recruited as a UNATCO agent. And people applied. People wanted to be in it. We got applications from military veterans, and we would look at these resumes that came to the office.

Todd: Something that was commented on multiple times in the reviews was that if you were being stealthy, you could overhear the guards discussing communist philosophy. That was the first time I’d worked on a game where that kind of philosophical attitude was exposed to the player.

Livingstone: I remember the excitement in the media about this innovation in gameplay. It doesn’t happen very often, but here it was.

Romero: We threw a big release party down in Austin, on the lake. We had the dev team out there and a bunch of people from Dallas. People took a picture of me in the water and that was up on Something Awful.

Livingstone: The sales goals were conservative because we didn’t know how hardcore the audience would have to be to play it. RPGs are not everybody’s cup of tea - by adding stealth and adventure and FPS elements, you could fall between two stools and end up appealing to nobody.

Smith: I remember standing in Warren’s office near the end and both of us were super worried about it - will people get it? And it had a lot of bugs. We were unwilling to compromise in some ways, and the framerate on some machines was really low.

Powers: I wasn’t convinced it was going to be a big hit. I was afraid that it would be too complex, and didn’t have enough faith in players to invest in it.

Bare: Making the game accessible was not something we were good at. I let my brother-in-law play it. I handed him the controller, Liberty Island booted up, and within ten seconds he had thrown his pistol and multitool onto the ground, walked forward into the water and drowned.

Romero: I thought it was pretty funny when I started playing. The meme happening back then was seconds to crate, and you start right behind a crate.

Grossman: I was a little surprised at the success of it. We had seen all the backstage stuff and the last-minute decision-making. The Looking Glass games were never big sellers. It felt like our corner of game design philosophy was being vindicated.

Powers: It was very validating. It really reached the people who had been waiting for it.

Romero: Eidos was so happy about it. It became a game of the year. It made up for all the other stuff that was going on. They definitely got their money back, so I’m glad I brought Warren on.

Livingstone: It was a big relief, I can tell you. We’d invested an awful lot of money without the return we were expecting, for Daikatana and Anachronox. I can’t really say whether Deus Ex made up for it, but it was certainly a welcome contribution on behalf of the whole Ion Storm enterprise, to come out with a winner. It not just sold well but had critical acclaim.

Legacy

Over two decades, Deus Ex reshaped games in its own image. The importance of the project has become clear to its makers mainly in retrospect.

Romero: It was definitely something a lot of designers looked at as an inspiration.

Pacotti: I would hope it drove home that there’s great value in making the player believe that the things they’re doing are real and have consequence.

Bare: It was extremely formative in the way that I think about games and approach design at Arkane.

Smith: It’s filtered into every other part of the ecosystem. The emergent interactions and environmental storytelling have been assimilated into lots of different genres. Going to work on Dishonored 2 or Prey, it keeps us on our toes. The same old tricks work, but you also need new tricks.

Grossman: Deus Ex did things that now seem normal.

Todd: I didn’t feel like we were making this grand statement. We were all just having a good time.

Romero: If I didn’t do Ion Storm at all, something else better probably would have happened. But if it meant that there wouldn’t be a Deus Ex, then I definitely would have gone through it all over again.

Bare: There’s a meme - every time someone mentions Deus Ex, someone reinstalls.

Smith: Every time the US shifts a little towards fascism or centralised control, somebody will send me a link to something from Deus Ex. It’s not that we were prescient - the sad part is that it’s on repeat through history.

Powers: We gave birth to UNATCO, a multinational secret police force that worked clandestinely and did these black ops around the world. There was this seed that hinted at our real world future that I didn’t take too seriously at the time.

Smith: You can really feel the change in 20 years as the internet has had its way with cultures around the world. You can look back and vaguely remember when conspiracy theories were just amusing, and not terrifying examples of people engaging in delusional magic reality thinking and doing hurtful things, or families losing people.

Grossman: I take it a lot more seriously now than I did then. Edward Snowden is a Deus Ex character. I have to say, I was a little more naive.

Smith: Deus Ex and Dishonored both involve a plague, and they both involve powerful, corrupt elites turning the disenfranchised against each other. When some states discouraged the wearing of masks or sheltering in place, somebody inevitably linked me the opening cinematic. ‘Why contain it? Let the bodies pile up in the streets’.