An Iberian Winter: Crusader Kings II Diary Part One

A Song of Lice and Ire

I've been creating all kinds of stories with Crusader Kings II and with the release of the Sword of Islam expansion I decided it was time to pen a chronicle or two. Somewhat experimental, this is history from several perspectives, being the tale of a thousand men and women, and the genesis of nations. This is how their world ends and how the modern world began.

Dust cascades from the ceiling as the packed tapial of the castle shudders. There are strangers above, ransacking the settlement where you spent the better parts of a life gone to ruin. This is how your world ends, although it would be more accurate to say that it ended on the day the soldiers came to your door and told you that you had the wrong friends in the wrong places. What friends, you asked, what places? Of course, they didn't answer. The dungeon has been your home since then, your only place, the old poet who has been discarded in the corner your only friend.

Every cough that rattles from his throat is death, decorated with ribbons of phlegm and blood. He doesn't speak although sometimes he sings, memories of the sea and a splendour impossible to associate with the rags and filth that clothe him now.

Civilisation is falling. In your lifetime you have seen it rise, from courtyard to coast, but with that power came a fragility as brother turned against brother, and confidence became arrogance. It is 1103 and the Aftasid Emirate is (might be, could be) in ruins.

"I was there at the start." It's like bone scraping on bone, a voice that hasn't cracked so much as shattered. "I will be here at the end."

This is the Poet's Tale.

In a world of brotherhood, I had only one sibling to my name, Sheikh Muhammad, a proud man and quick to anger. He was younger than me but that did not stop him from besting me, in a most improper manner, in whatever pursuit he could. Falconry, hunting, war and womanising - he showed superiority in all, But there was one sphere in which his strength and charm could not outshine my own talents, for I was the poet of the family.

My father, the Emir Abu-Bakr, peace be with him, was the ruler of the Aftasid Emirate, which stretched from Caceres to the Portugal Coast, and it was there, watching the waves and the fishing boats, that I spent the happy days of my youth. Now I am more accustomed to the salt taste of my own life's blood than to the knife-sharp air of the sea. The only waters I see are thrown in my face by the thugs who keep me alive in this dank hole only so that I can suffer needlessly, unseen by those any who know my true name.

Were you taught the finer arts, the theatre and the song? I was. Even my wives found my love of words to be an effeminate weakness, putting their faith in swords instead. That is the truth of this time; violence is valued over contemplation and, to coin a phrase, blood will have blood.

Murder is a terrible way to prove oneself, especially to a father who does not seem to understand that there are other ways of existence. It was not enough to leave me to my learning for until I had fought and survived, he saw no reason to believe I was a man at all. To make matters worse, although my wives were fine women I had no children until my thirtieth year while Mohammad, my brother and my betrayer, had three fine sons already.

It was before the birth of my first son, before I had created a life, that I first killed a man. In the cold of 1068 I had travelled to the mountains in order to oversee construction of a fort. Meanwhile, my father undertook a great pilgrimage and, perhaps believing that the Emirate would be weakened in his absence, the Christians attacked. They have long desired to 'liberate' these lands, though they have no historic claim to them, and the worst of them, mad King Sancho of Castille, marched on the small Sheikhdom of Aragorn Aragon (ahem) in the north.

Armies were mobilised in defense of the faith, our own soldiers backed up by our more powerful neighbours, the Dhunnunid, and the paranoid and bloodthisty monarch soon saw the error of his ways. It is with regret that I must admit my part in the decades of conflict that followed. Although I am not a violent man, I could not tolerate the infringement or the foolishness that inspired it. This was a war that Sancho could never win and yet he sent his knights to die, their minds clouded, confused by lies they had been fed since birth.

I see now, given the trauma that followed, that those same lies are uttered by fathers of every faith. Sancho's armies were turned back easily but to prevent him from striking against us again I gathered my courage and marched to the cities of Castille, surrounding them with the thousands who followed my banner. Negotiations followed and it was there that my knowledge of ancient texts and prosidy became a boon. We took Sancho's lands, leaving him to cower in the distant North.

As soon as my father returned, he saw the lands I had won and divided them among his children. I, the architect of this expansion, received nothing.

Even those with good reason to hate their parents often feel compelled to impress them. Our ancestors are our personal pantheon, the tangled tree of family a confused reminder of the universal oversimplification that monotheistic principles can represent. You seem surprised. Perhaps you believe my words to be heretical but are we not both damned already? Besides, my faith tells me that a word used ill is never so opposed to the true dictates of Islam as a sword used well. In better times this will be understood.

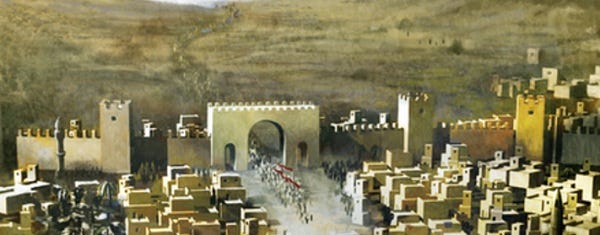

It was the desire to impress my father that took me back to Castille. I commanded the troops as they laid siege to what would become Sancho's final resting place. Have you ever witnessed a siege? There are no banners unfurled in the breeze, no bright armour or flashing blades. The walls are piled high with human waste. The woman and children are the first to die, or to defect, surrendering themselves to the horrors a man far from home can inflict, half mad with fear and lust.

Eventually with enough time and pressure, the box breaks open and the remains spill out. A flood of dehumanised humanity, starved patchwork scarecrows, their once-white garments blossoming with the flowers of disease. They are like horses fleeing a burning stable, their teeth bared, their eyes turned back in their skulls to blot out the sight of life reduced to panic and ash.

It was there that I abandoned any inclination to be the warrior my father wished me to be. If the sights weren't terrible enough, I received scars of my own in a fumbling clash with a fleeing boy no more than fourteen years in this world. As he died he gasped out a word, a name, and lashed out with a dagger in his first. I lost, as you can see, the fingers of my right hand and now my words are dictated if they are ever recorded at all.

I needed to feel clean and as soon as my fever had subsided, I set out on the Hajj, half-hoping never to return to the blood-soaked peninsula. Age had crippled my father and he barely left his bed, although he still seemed shrewd enough to rule for now. The time would come when I took his place at the head of the Emirate though and I feared that day more than any other, sometimes dreaming that all of our lands would be reclaimed by the Christians, leaving only a castle on the coast, enough space to keep me content for the rest of my days.

The old man had other ideas. I returned from Mecca with blisters on my feet but with no revelation in my heart, and once more I found myself at war. The King of Galicia had died a few weeks before leaving his realm with no ruler. The infant who wore the crown would become the bravest survivor of the Iberian conflict, but for now Justa was three years old and she had no friends. Not only did every Sheikh and Emir send troops to support the Abbadid assault on her lands, her Christian neigbour, Alfonso VI of Lyon, saw a prime opportunity to extend his own holdings and turned against her as well.

I hear that there are regions of the world where Moslem strikes against Moslem, but in my life I had not seen such troubling treachery until the events that brought me to this pit. The Christians have no sense of brotherhood, their constant infighting is the only barrier to total dominance, for the armies of France are no doubt the mightiest in the world. But what use is might when it is turned against itself?

The young Queen was smuggled to safety, her armies decimated by the tens of thousands marching under the flags of my father and the ever-hungry Abbadid. I have already spoken of the fool desire to impress, to leave a mark and to be remembered. While Galicia fell, I gathered the men of my own Sheikhdom and we routed the armies of Lyon. I believed it to be a just strike for had these people not turned against a child of their own faith in her moment of greatest need? They deserved to die.

A few months later, the north was entirely ruled by the Abbadid and my own father. The lands that I stood to inherit were large and varied, many still inhabited by men who spoke a bastardised tongue and prayed to their own foreign god.

With Galicia and Lyon reduced to scraps, I spoke with my father, at his bedside, and told him that the time was right to rid our world of infidels entirely. It was not for glory that I suggested this action, nor to see the gleam of admiration in his rheumy eye. I say, and it is no lie, that I sought only peace and the squabbling Dukes would never sheathe their blades, either cutting at each other or dying in rash invasions of the Sheikhdoms of the east, who relied on us for protection. The worst of them lives near the French border, the ancient Duke of Barcelona. His frail body will give up its ghost soon and then we will seize those lands, creating a treaty with the Kingdom of France, drawing a line in the mountains that separate them from us and promising never to cross it.

But even the Christians, so quick to war with one another, have their limits. The last of their kind in Iberia realised that our 'new' faith is set to supplant them entirely and they put aside their greed and fought side by side for the first time in a generation. It was too late. We were too many.

Lyon fell but Queen Justa, the infant survivor who is now a young woman of worth, refused to be defeated. Rather than waiting for the inevitable collapse of her holdings, she rallied what troops she could and sent her greatest general to burn and pillage our lands while our armies were distracted in the north. Incredibly, Castelo Branco, in the heart of the Emirate, fell to the upstart and even though the rest of her lands were divided between an assortment of Sheikhs, including my own sons, the terms of our treaty allowed her to live in the midst of her enemies.

My first-born, Abu-Bakr after my father, was appointed Sheikh of Leon and, I am proud to say, he was a kind ruler, allowing the Christians to trade and live on in those lands without prejudice. I still feared the day that such choices, the division of rule and responsibility, were mine to make but my father, bed-ridden for years, showed no signs of releasing his grip on life.

So proud was the old man that he thought it wise to send me, his heir, on a campaign in a distant land. Ghana, of which I knew nothing, was under attack and had requested assistance. The spread of our lands had made us powerful enough that the wider world now took notice. It was the first time I had ever travelled such a distance by water and seeing the glittering coast of storied Rome made me realise how small the plot of land I had fought over for most of my life truly was. There was such activity there and I was reminded of the days of my youth, when the sand, dirt and sea were the beautiful limits of my world.

The war, such as it was, had ended before I arrived with my small retinue. Perhaps because the journey had shown promise of an impossible future as well as a past more dream than memory, on the return home I felt that the best of life was behind me. I had grown old and gray, and what had I achieved? I feared the power that would be mine and regretted the battles I had won and the treaties I had constructed.

Apart from those few holding out on the French border, Queen Justa was the only Christian ruler still living Iberia, the others are fled or finished. She conducted herself with dignity and learned the customs of our courts. It was only right for, after all, did she not come of age among us? When I returned from Ghana, however, her people were being assaulted once more and in the chaos it took some time before I could find anyone willing to tell me what had happened in my absence.

A stranger who claimed to represent my brother curtly informed me that my father had passed away and Muhammad, my younger, more brilliant brother, had become Emir. It was a relief not to be responsible for so many and not to be the one who must decide the fate of the brave young woman whose only fault was being born to the wrong family and in the wrong faith; it was a relief but it was also the final blow against my dignity, the confirmation that I had never been good enough. Mockingly, my brother received me at his court and in a trumped up display granted me an official title. Not Emir, for he could have split all of those lands in twain and allowed me to serve as an equal, not even Sheikh. He made me the court poet of Badajoz.

When Queen Justa's castle fell in 1095, I begged an audience with Muhammad and asked him to show clemency, to allow her to leave for France where she has family and friends. He complied but not before humiliating me once more, telling all those who heard my plea that I had fallen in love with a "Christian whore". I never even saw her face, although she was imprisoned, for a while, in this very cell. So I am told.

Two weeks later I was brought to this place. His whole life he has known that he is better than me, he has known that I would never threaten him and that I despise the power that he craves, but still he cannot take the risk of having me free. We are here, all of us, because they fear our blood, our heritage or our words. Those things all carry more power than swords.

That is all I know for sure and I have been here for years that I cannot number. My brother was killed, so the guards say, by his own son. I almost imagine he smiled as the assassin's blade plunged into his heart, knowing that he had taught the boy, Umar, the ways of power and survival.

Before that, so I am told, my beloved son Abu-Bakr did launch a stubborn attack against Muhammad. I like to think it was to liberate me but don't doubt that other political machinations had a larger part to play. He died in the cell next to this one. They disfigured him first, with heat and metal, so that he could not see or hear. My words of comfort were wasted but every cry of his cut me deep and his silence still screams out every morning when I awake.

There is only confusion now. Different guards every day, each speaking in a different dialect. Some are from the south, I know their voices, and others speak like the Dhunnunid. The Emirate is falling and, just as in my own family, brother has turned against brother. But none of that matters to me anymore. I nurse my crippled hand and dream of the sea, speaking my stories to the air and hoping, one day, to have a friend who will remember my words.

Three days later, the poet, Yayha of Lisboa, dies in his sleep. Although he was instrumental in the conversion of Iberia nobody will remember him, just as nobody will remember you or hear the story of your own life, such as it was. Ma'al salam.

History continues to be made in The Queen's Tale, in which there is farce and tragedy as the fate of Queen Justa is discovered and France continues to be the most squabblesome place in the entire bloody world.