China forced one horror game publisher to close, but the whole region felt it

Devotion to the "public interest"

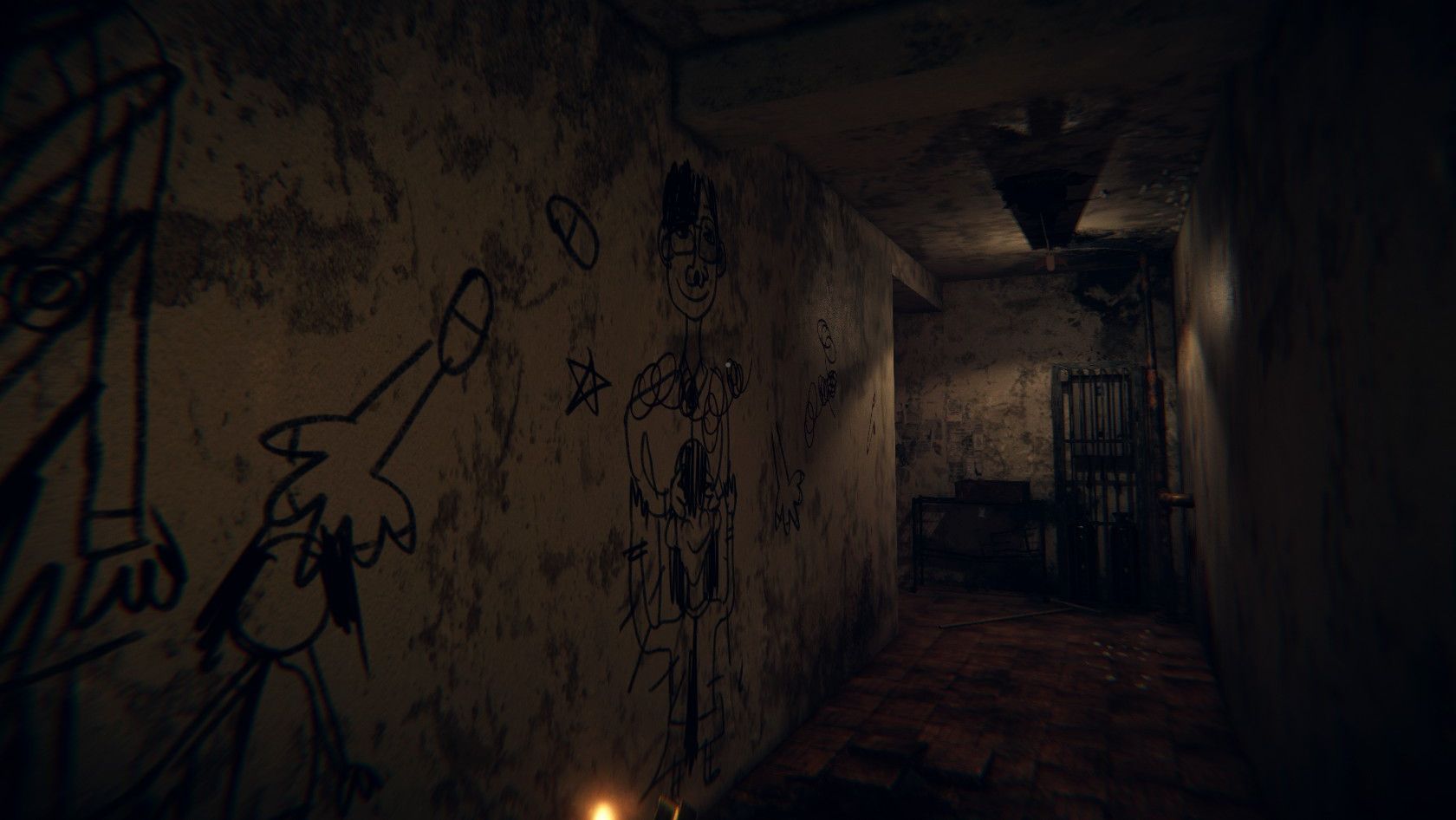

Much like the phantoms that materialise and disappear within the dusky corridors of Devotion, the game itself felt like an apparition. Launched in February, the solid Taiwanese horror game vanished from Steam just weeks afterwards, due to the discovery of in-game talismans that contain derisive references to China’s President, Xi Jinping. Facing a firestorm of criticism, its studio, Red Candle Games, hurriedly hunkered down, announcing that it was putting the game through rounds of quality checks before releasing it again. But it's now four months later, and the game still hasn’t been restored on Steam. But Red Candle aren't the only studio that has to wrestle with China's strict censorship.

More troubling news has since surfaced: the Chinese government revoked the business license of the studio’s Chinese publisher, Indievent, stating that the company has put China’s national security and public interest at risk. This is undoubtedly another blow to Red Candle Games, who recently told people the game would not return to Steam "in the near term". However, this news didn’t come as a surprise to the developers and publishers I spoke to in the region.

“The Chinese government already has an extensive history of media censorship, and I see this removal of a publisher’s business license as the next step in that practice,” said Johnson Siau, from Hong Kong studio Pixio. He’s curious about whether Indievent will recover its license, perhaps by establishing a new company, but he isn’t ruling out the possibility that the state will punish another developer or publisher in the same way in future.

China is the largest gaming market in Asia Pacific, and is estimated to generate a whopping $36,540 million in revenue this year. The country commands huge economic clout. Yet to understand the implication of Indievent’s closure, we need to address the thorny issue of licensing in China.

The country’s strict scrutiny of videogame content means that the process of acquiring game licenses is extremely challenging. Even major domestic publishers like Tencent has had trouble, and were only awarded the permit for just two mobile games, in January this year. Things have been harder thanks to a nine-months game license freeze from March to December last year, in which no licenses were granted at all, an enormously trying period for studios in China, which could not sell their games until they got the licenses.

“It’s hard," said Iain Garner, who runs Taiwanese publisher Another Indie and publishes games like Lost Castle. "Labyrinthine and ever-changing. Seems like things might be settling a little now but the sheer effort required to submit would be a brick wall to most developers.”

It’s not hard to see why many Asian studios are reluctant to devote their time, money, and effort to this.

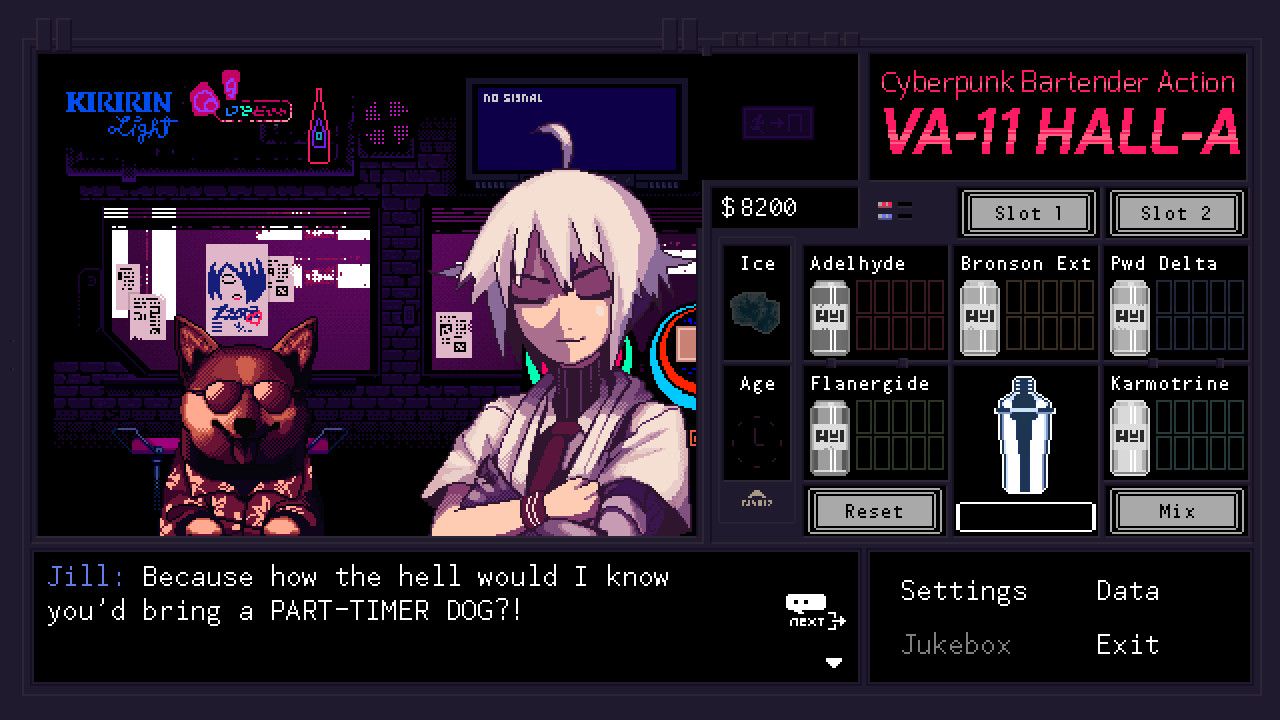

“Admittedly we haven’t tried,” said Brian Kwek, owner of Singaporean publisher Ysbryd Games, who publish games like cyberpunk bartend ‘em up Vallhalla. “I have some insights on what you can do to get the ministry’s approval and all. Basically it takes time and a lot of energy, and for what it's worth, Ysbryd is a pretty small organisation and we kind of have to pick our battles.”

Instead, some studios choose to release their games on Steam, rather than go through the laborious process of seeking the necessary permits. Steam is accessible in China, even though its operation is technically illegal. As such, Kwek considers China as a secondary market for the games his company publishes.

“As you may be aware we publish titles like Vallhalla, which have done pretty well in China,” he says, “and we definitely have other titles that did not move a needle at all in China.”

To an extent, many studios and publishers felt that one horror publisher's license being revoked would have little direct impact on how they develop games, because companies like Kwek's aren’t planning to apply for a Chinese license anytime soon.

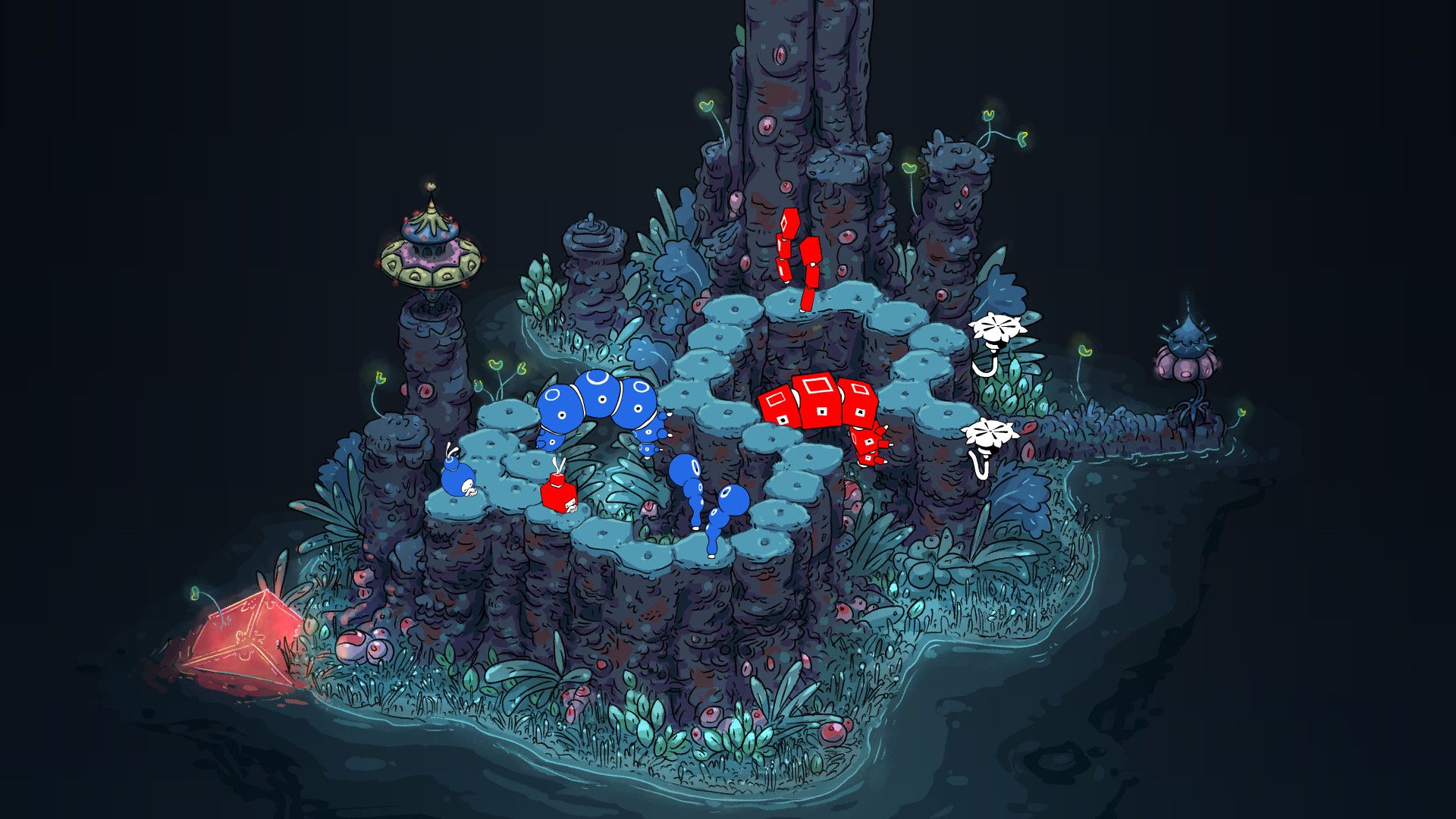

“Almost all of our games, save for maybe She Remembered Caterpillars, have something that could be marked as culturally insensitive and not fit for public consumption in China," Kwek said. “And depending on the developer we work with, there is a point where we [ask if it’s] worth their time and energy to repurpose the game, so that it is fit for the China market."

Beginning in March last year, China stopped granting licenses for games and didn't star handing them out again for nine months, with this incident significantly hurting many games studios in the country. Even industry giants Tencent saw its profits plummet, while smaller games companies struggled to stay afloat. This license freeze dwarfed the debacle surrounding Devotion, according to Xuan Li, the co-founder of Zodiac Interactive, a games publisher based in China. They’re still trying to get their first game on a Chinese gaming platform even today.

“The freeze of gaming license approval last year made it impossible for us to bring overseas games to the Chinese players,” he said. “My assumption about the freeze was the government took time trying to figure out stuff like ratings, the import of video games, parent control, which I think are necessary. Then it turned out it lasted for almost a year and we still need to wait for a long time to have the clear policies about those things. The Devotion misfortune certainly can’t compare to the total frustration of the Chinese video game industry in 2018.”

And as a Chinese studio, Zodiac Interactive isn’t worried about crossing the line. If anything, it is intimately familiar with the line, and is already avoiding projects that strongly relate to political issues in China. Siau from Pixio and Gander from Another Indie echoed this sentiment as well.

“We’re already aware of certain depictions that are sensitive in China so we simply avoid them as we have before,” said Siau.

On top of this practice of self-censorship, Li felt that Taiwanese game developers may already be at a disadvantage following the Devotion controversy.

“I don’t see any of the Chinese companies approaching… video game developers in Taiwan any time soon. Some have terminated the partnership with Taiwan-based companies right after Devotion got pulled from sale,” he added.

Meanwhile, Kwek, the publisher of Vallhalla, believes that Indievent’s closure isn’t a problem that is exclusive to studios in China and Asia Pacific. The issue is a lot broader, he says, and can happen to studios even outside the region, as long as there is inflammatory content in the game. I asked if this deters him from publishing Devotion or other Taiwanese games, and he said the crux of the issue isn’t about the politics per se. Rather, it’s about how audiences and players react to news online, and the intense backlash that typically follows.

“I think what publishers are concerned about is [if] the backlash on Devotion spills over to the other games. If I publish Devotion - and if this becomes news for whatever reason, which I'm sure it would - the folks who took offense to Devotion [may] decide to review bomb Vallhalla and all the games by Sukeban Games (the developer of Valhalla) just because the publisher supports Devotion. It's irresponsible to my existing partners to allow that to happen to them.”

Likewise, publishing any game that may rile up players is a cause of concern, although he says this isn’t about sanitising the game’s content, or about any perceived fear on tackling politics in games.

“Life is inherently political, so this is a question of [whether developers can] tell these stories in a way that, instead of inciting and inflaming our differences, gets people to relate to the stories that are [being told]. As long as the story remains relatable to the audience, I think that's the key.”

Garner is also wary of an containable backlash in China, given the huge population of Chinese gamers.

“When something offends the Chinese populace, it can make the average twitterstorm look like a lover’s spat. What’s worse is that Chinese gamers don’t have access to the Steam [discussion boards] so they tend to vent via reviews which can massively damage a game’s standing on Steam.”

Despite the heavy-handedness of China when it came to Devotion’s publisher, other studios are confident this won’t affect the way their studio makes games. Mark Fillion, Creative Director of Singapore-based studio General Interactive, says it won’t change the way they market their games to China, even though the Chinese market has been the third and fourth largest source of sales for its game, Terrior.

“I believe a game should never compromise the integrity of its story and the feelings it is trying to evoke just to appease a certain segment of the audience, let alone a government,” Fillion told me. “Chinese gamers, just like everywhere else, have incredibly diverse outlooks on their lives, their country and the world.”

He did, however, say that it’s simply not safe to openly express anti-government sentiments in a public platform, which led to a vocal minority dominating the conversation around Devotion.

The ripple effect may still be palpable among regional developers, however, with Siau believing that these events may make it more challenging for studios looking to publish their games in China. Chinese publishers are probably a lot more cautious now, since they know that their business licenses are on the line if they screw up. With China, he felt that there are still further developments in this unfortunate tale yet to be unveiled.

“Ultimately though, I’m mostly waiting on further development,” he says, “as the whole media censorship department in China is pretty much a black box and I have no idea what they’ll do next.”

On the other hand, Li wanted to reassure regional developers that it’s still possible to sell games to Chinese players, if they still wish to do so.

“The developers outside of China already know the strict policies here, such as no skeletons, no ghosts, no sex scenes, no blood splash. If they want to expand their fan base in one of the biggest game markets in the world, don’t call names at the current President.

"Jokes aside, the vast player base in China means great opportunities. Talking to local publishers like us might help you dearly.”