How historical games integrate or ignore slavery

And how they can do it better

Video games always come with an expectation that the player will suspend disbelief to some extent. Genetically engineered super-soldier clones don’t exist, radiation has never and will never work like that, and overweight Italian plumbers could never make that jump. In most cases, if we are unwilling or unable to suspend our disbelief, we may well struggle to enjoy the game and our questioning of the basics of its ‘reality’ would probably make us insufferable to be around.

There are some games however, where the realities of our world are key to enjoying the game. These are the builders like City Skylines, simulators and sports games like Prison Architect and FIFA, and even crime games like Grand Theft Auto. One genre has a particular problem when it comes to maintaining a foot in the real world yet still creating a setting where one can have fun without becoming mired in morally questionable events and choices: historically based games. And among historical games, few subjects are as complex to represent as slavery. Many have tried, from Europa Universalis IV and Victoria II to Civilization and Assassin's Creed: Freedom Cry, and in this article I'll investigate the portrayal and use of slavery in these games and more to explore what they get right, what they get wrong, and how games could do better in future.

If you’ve enjoyed a World War II strategy game, you may well have also enjoyed the thrill of storming the gates of the Kremlin with your Panzer tanks. Everyone who has climbed into the cockpit or cupola of a tank or fighter simulator has enjoyed blasting apart Allied or NATO equipment. It’s simply fun to play the bad guys sometimes and to change the course of history. Of course these games give us a way to escape the consequences of the new history we’re writing, we don’t have to see Europe under the Third Reich, and even in the time period the games cover, the German forces don’t fully resemble the Nazis. No swastikas, no talk of the final solution or concentration camps, just vaguely authoritarian overtones, cool tanks, and, for the victor, a sense of accomplishment.

Game designers long ago realized the best way to deal with the political and cultural consequences of a fascist victory, and the human cost, is to concentrate their efforts on the war itself. No ideology, no symbols, no politics. Just the fighting and the challenge; and it’s worked. No one really complains. It’s when we get beyond explosions and win screens and start dealing with building a civilization, exploring how societies work, and introducing the human factor that dealing with history becomes more complicated, and slavery is a perfect example of that.

Many games have approached the problem of slavery in one way or the other with varying degrees of success or failure. For some, the issue is approached with sensitivity, in others with jaw dropping cluelessness. By looking at what’s worked and what hasn’t, we can attempt to see how game designers can approach the subject effectively and appropriately.

Playing History 2: Slave Trade

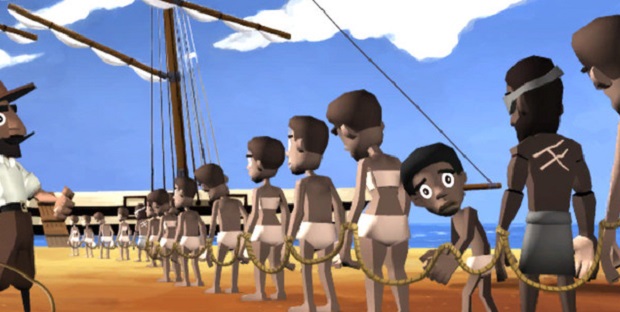

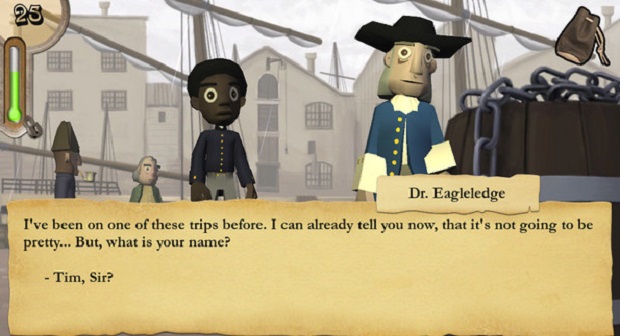

Educational games don’t have a glowing reputation at the best of times, Frog Fractions aside, but few have missed the mark as badly as this one. Playing History 2: Slave Trade is supposed to educate pre-teens about the horrors and tragedies of the Triangle Trade, where slaves from Africa were shipped to the Americas to produce goods that were sold in Europe, but it fails on almost every front. Cartoonish characters and bright colors render the tone of buying and selling human beings a farce, and not in an intentionally comic or satirical Monty Python or Mel Brooks kind of way. Rewards come when players succeeds at being good slave traders by, for example, getting to America safely.

The most notorious part of this game, the “Slave Tetris”, shows a mind boggling level of tone deafness. One has to try to stack as many slaves into the hold of the ship in a Tetris like mini-game. While slaves were in reality stacked into the holds of ships like a grim Tetris, making it into a ‘fun’ mini-game obscures the actual horrors of it. It’s the combination of mechanic and aesthetic rather than one thing or the other that is so disastrous. Brenda Romero’s The New World, a physical game made as a sort of educational supplement for her daughter, also gamified the slave trade, but did so in a way that highlighted both the coldness of economic considerations where human lives are currency, and faceless figures that emphasised the inhumanity of the process.

Slave Trade operates by making the process of being a good slave trader the rewarding part of the game, and that’s only made worse by the fact that the protagonist in the story you play is a young slave boy. The only lesson for game makers to learn here is how to do everything wrong.

Europa Universalis IV and Victoria II

Paradox Interactive, one of the premier grand strategy game studios, has an interesting and intelligent way to approach this difficult subject in this pair of games. EU IV, which begins in 1444 starts off in a period of human history where the morality of slavery was not heavily questioned by philosophers or religious authorities. In fact, many of the great thinkers of the period actually allowed and condoned slavery as long as those enslaved weren’t of the same religion. This is reflected in the game; slavery and slaves are reduced to simply another economic resource to be exploited.

As one explores the world and opens new markets, slaves become just another commodity to be exploited and traded, like coffee, tobacco, and gold. While certain events can be triggered in the game where slavery can be outlawed by a nation or condemned by the Pope, it really only affects the economics of the game. One has to remember that the scope of this game is more on building economic prosperity and an empire, and so other human factors such as economic class and education hardly come into play. However, Paradox makes up for this in the ‘sequel’ to the game, Victoria II.

Victoria, set in the 19th Century, a game where the human condition plays a much more prominent role, tackles the issue of slavery in a way that few if any grand strategy games have before. The social pressures of class, oppression, and representation are a key component to building a prospering and competitive society. Slaves, in a way, actually hold you back in the game; they cannot purchase luxury goods, have no right to vote, and have very small life needs. This translates out into a high level of militancy and therefore greater chances of rebellion. These rebellions can derail your plans for your country and actually threaten your choice of governments forcing you into ever more repressive regimes.

Even if by freeing the slaves by choice or by violence in the American Civil War, you’re still left with an agitated lower class ripe for anarchists and communist agitators to make your plans for a plutocratic or autocratic society a nightmare. In a roundabout way, Victoria teaches you that slavery in the end causes social issues that modern societies cannot prosper in, and can actually hold back the ideas of social prosperity. While never handled in a deep and profound morality lesson way, it works for a grand strategy game.

Civilization IV and Civilization VI

While Paradox Interactive games are often seen as the domain of hardcore strategy gamers who are willing to devote hours and hours of their lives to spreadsheets and micromanagement, Sid Meier’s Civilization series is the everyman of strategy gaming. The games allow one to play through the whole of written human history, from scratching the earth with sticks to launching ships to other stars, with all of the variations of invention, social values, and governments able to be played with, including slavery. This is where Civ runs afoul of a problem with whitewashing in its latest incarnation.

Back in the fourth incarnation of the game, slavery was one of the ‘civics’ or social mechanics one could choose from to build their nation with. In 1999’s Civilization: Call to Power there were actual Slaver units, and Abolitionists with which to counter them. Neither of those iterations really delves into the morality of slavery, but they do deal with the reality of it with a few mechanics. In Civ IV, under the slavery mechanic, one could chose to sacrifice two units of city population in order to rush production on a building. Appropriately players took to calling this ‘whipping’. While yes, you were able to rush a building at the sacrifice of population, it came with the additional punishment of increasing ‘unhappiness’ on a civilization which can cause all sorts of negative game effects including civic unrest. Of course hard core gamers figured out ways to mitigate the effects of this.

However, in Civ VI, slavery, along with many other ‘darker’ aspects of human civilization just doesn’t exist. Despotism, oppressive religions and others all seem to be simply removed from the game. In fact, only one playable civ in the entire game is able to utilize anything resembling slavery and that is the Aztecs who are able to capture enemy units and use them to build improvements. This comes with not only no penalty, but is seen as a bonus to the civilization. The disparity was noticed to the degree that players have already starting building mods that allow other civilizations to feature this useful mechanic since workers now expire after only a few projects.

The Civ series has gone backwards in addressing this aspect of human history, not in just removing it as a mechanic, but making it a useful thing to have with no negative impact on the player in any way. Arguably, this makes the series worse in that it is no longer engaging in the complexity of an important aspect of historical development. Making slavery advantageous with no drawbacks, or removing it from history entirely, can actually be damaging when considering reconciling the past with making gaming fun, and the Paradox series are superior in this regard. Civ used to get it right, or at least approach the issue more effectively.

Assassin’s Creed

Assassin’s Creed: Freedom Cry allows puts players in the role of Adewale, an escaped slave fighting against slave traders and freeing enslaved Africans. While Adewale has all the powers of an Assassin, he still can’t quite exist in the game like a white protagonist. Bearing the mark of an escaped slave, he cannot move about freely in town and must constantly be on guard, which is a way to reflect the second class nature of being a black man in the era of slavery.

Yet much of this lesson is overshadowed by the way that Adewale is rewarded by freeing slaves. It’s not that he progresses the story by freeing them, but that the game treats them as a resource. He receives power ups, enhances his game play, and generally benefits from the existence of the slaves in ways not dissimilar to the slave owners themselevs. Yet, when one looks beyond this at the background action that the player doesn’t directly interact with or chooses not to, one can still see the brutality of slavery in place.

Players can witness slave auctions occur, seeing free-thinking -feeling people being treated as simple commodities to be bought and sold. Escaping slaves can be helped or ignored, only to see slave masters beat and kill the slaves for having the audacity to try to be free. Masters cruelly mock and work their slaves to death, and disregard their pleas and protests. Some of the horrors of slavery are there to witness and experience, but the mechanical flaws of the game overshadow the portrayal at times, and it often glosses over some of the worst aspects of ownership, such as sexual assault and the separation and destruction of families.

Many articles have been written about the complexities of the game’s treatment of the topic of slavery and where it falls short. However, it made an effort where many other games set in a similar era would have simply ignored this fundamental aspect of the society that is its setting. It’s not a perfect game, but it goes places where others would not, and for that it does deserve recognition.

Fallout III and Fallout: New Vegas

You might be wondering why two games set in the future of a world with an alternate past are doing here, and there’s a good explanation for that. In the study of the past there is this aspect historians look at called ‘historical memory’, which is the way that people and groups choose to remember the past and build narratives and identity around it. When it comes to slavery, it can be both a negative, as when some American southerners yearn for the days of the Confederacy, but a positive in how we reflect on how we grew to recognize that owning another human being is so morally repugnant. No matter the studio behind the games or their main plot, one running theme throughout the Fallout series is how the people in the Wasteland see the past in their present. In modern RPGs, players enjoy the freedom to make moral choices, and open-ended games like those in the Fallout series are no exception.

In Fallout III slavery is a minor aspect of gameplay, comprising only a few side quests that aren’t ultimately necessary to the game, but do lend to the atmosphere in playing in the ruins of America’s capital and its past. Of course players know well that somewhere in the setting’s past America went off the rails and became a brutal oppressive state in its hunger for natural resources, yet as society became more brutal, some things were still revered, including basic human freedom. As one goes through the wasteland, one can choose to side with the slavers in Paradise Falls, and sell and trade slaves for a few caps, or side with the escaped slaves at the Temple of the Union, who revere the memory of Abraham Lincoln and his freeing of the slaves to the point of wanting to set up a virtual temple in the Lincoln Memorial.

Through either choice of action, one thing remains clear for the Lone Wanderer: slavery is the amoral choice. Whether it’s through earning negative karma which restricts the player’s interactions with other characters, or having to actually destroy a slave revolt and help suppress the memory of Lincoln, the Civil War, and the ending of slavery, you never get to escape the fact that aiding and abetting slavery is fundamentally an immoral act.

In New Vegas, Caesar and his Legion are tied to slavery. Caesar treats the weak with nothing but contempt and sees them only worthy as slaves. Of course these slaves are only good for menial tasks around the camp, supplying food, clothing, and violent entertainment in the arena where they are made to fight to the death. There is the implication that slaves can be sexually assaulted with impunity. Even in this post-apocalyptic hellhole where what’s right and wrong is not always clear, it’s obvious that the Legion and Caesar are purely evil and driven by humanity’s cruelest impulses. While again, Fallout allows the player to make open ended moral choices on whether or not to side with the Legion or destroy them in the game’s climax, there is no escaping the fact that they are the villains and siding with them makes you one yourself.

Through both games, it remains clear that despite the devastation of a nuclear war, the collapse of all the old values and rules of the old world, it’s not only war that never changes, but the core values of what is right and wrong. Are there shades of grey in the world of today and the world of the post-apocalypse? Of course there are, but some things remain good and evil no matter the circumstances.

When developers try to create games that deal with the moral complexities of humanity and society, they are always treading on dangerous ground, especially with a subject as dark as slavery. How can you approach the more awful aspects of history and society in a game without becoming heavy handed? How light can you go without ignoring the realities or making a mockery of them?

With games like Playing History it’s clear that trying too hard to make the game fun and accessible can result in not only an unsatisfying game, but accidental racism and tone deafness, no matter what the original intentions. Europa Universalis and Victoria manage to find an appropriate balance within the time frames and settings they work within, and apply vastly more complex moral issues to their games while maintaining engaging mechanics, which is at odds with Civ, which erases those complexities in the name of accessibility. In the more tricky waters of the action genre, Assassin’s Creed should be praised for creating strong, engaging, and entertaining minority characters and having the courage to place them in settings that are morally uncomfortable and complex, but it doesn’t manage to get the tone and mechanics just right. Fallout is an improvement, partly thanks to a setting that explores historical aspects of culture from afar, and partly due to its more open RPG structure.

There is no correct way to portray something as dark and cruel as slavery, particularly for developers attempting to work within the traditions and rules of a genre (no matter how many rules they’re willing to bend or break). Yet, topics like this will continue to play a part in games and gaming culture because they are part of our history and culture. People will continue to be offended by some or all aspects of implementation, and people will criticize or praise partly in relation to how well a game represents their own views or understanding. Game companies should never shy away from topics such as this, but they should bring knowledge and cultural awareness to any representation of slavery.

Avoiding the ‘fun’ minigame approach of Slave Trade’s human Tetris, and maintaining a level of cultural awareness and sensitivity, is important, but Assassin’s Creed shows how even a relatively historically sound inclusion in the setting can be undermined by the systems that drive play. One solution, as in Brenda Romero’s physical games Train and The New World, is to make the ethical element a subversion and extension of the intrinsic goals. As soon as the setting is made explicit, to win the game by its own rules is a failure.