How an amputation saved Quadrilateral Cowboy’s life

Kill your darlings

This is The Mechanic, where Alex Wiltshire invites developers to discuss the difficult journeys they underwent to make the best bits of their games. This time, Quadrilateral Cowboy [official site].

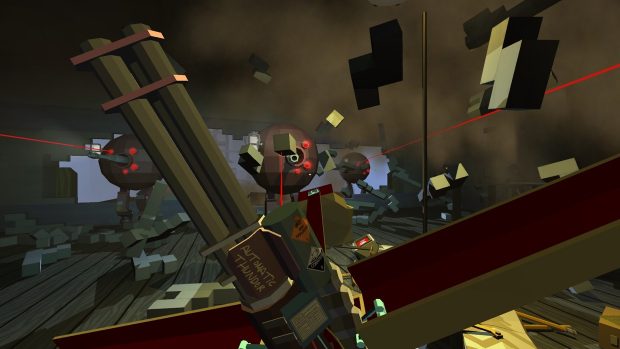

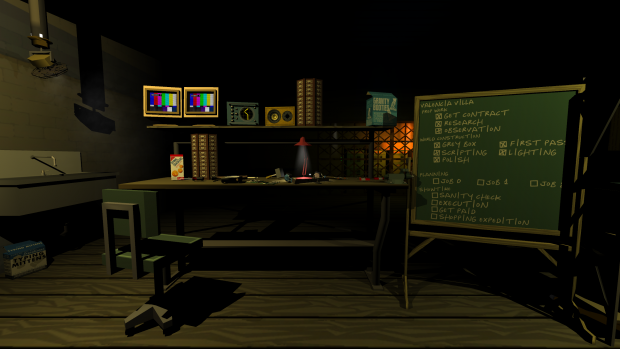

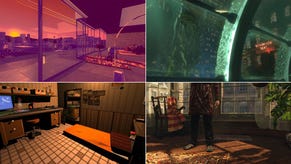

Quadrilateral Cowboy is a firstperson puzzle game about a group of hacker friends who stage heists across a set of increasingly challenging missions. Together they tell a surprising and affecting story of professionalism, friendship and rising threat through Blendo Games’ distinctive tight cutting between interactive scenes, flipping the action from a hoverbike chase to the gang’s return to their hideout. It’s clever, pacy, and rich in detail and nuance. Pretty much, in other words, what you’d expect from Blendo Games.

But it’s not what Blendo Games - which is to say, Brendon Chung - expected to make. Quadrilateral Cowboy’s entire structure and form is completely different to what he originally envisaged. The way in which his game changed over the course of its development is a model for how a game is shaped by the realities of production, and how ideas can be far too big for their own good.

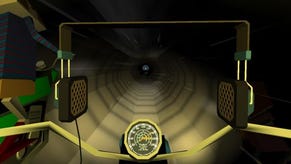

”What I wanted from the beginning was a game about hacking and a game about typing things into a computer and it being really chunky, ‘80s technology,” Chung tells me. The sense of that technology - oversized and awkward and yet resolutely practical - is personified by the deck in the final game, the computer you jack into security systems and computers in its maps to give them command line instructions. But he originally wanted that analogue feel to infuse the game so deeply that it extended outside it, right the way to shipping the game with a book in PDF form, written and presented as if it was from Quadrilateral Cowboy’s universe, which players would print out.

“The idea was that the book would have information about the security systems, so it would have an appendix table of all the model numbers for a specific door alarm system. You’d have these long serial numbers and in the game you’d zoom into the builder’s plate on the door and it would show what year it was made, what model number it is, and then you would in real life open up your book and flip through the pages and have to cross-reference the year to the model number and all that, and from that you’d figure out what wires you had to cut or what commands it has built into its microchip.”

Oh my god it sounds so good. It’s a similar kind of stunt to the one Zach Barth pulls in Shenzhen I/O, which also features an in-universe PDF manual which is pretty much mandatory to be able to flip through as you play so you can understand Shenzhen I/O’s arcane workings. “There’s something really wonderful about holding this physical thing in your hands that’s an artefact from the game you’re playing,” says Chung. But though he admires the lost art of game manuals, he was actually more directly inspired by Far Cry 2’s map, which exists in-game and in realtime rather than in a menu screen, so you have to look down at it as you stumble around the world or career down some trail in your jeep, glancing up to avoid hitting trees and zebra.

Quadrilateral Cowboy’s manual would be this thing you’d consult to solve puzzles and also to figure out where to go next. The missions were to be seeded across various discrete maps (Chung’s engine of choice, Doom 3’s, wasn’t designed to create sprawling open worlds), so you’d read the manual to learn about relationships between the characters and discover where objects you needed were to be found, and then you’d fly over to the location to start the mission.

“I thought there was something really juicy there and I was excited to do it, but as I started to flesh it out more I started to have strong doubts about the idea of players printing out a book,” Chung says. He worried that it’d present a barrier to entry - you’d need a printer or the time and funds to visit a print shop - and was put off by the idea that players’ first few minutes with the game would be a massive message telling them to locate a file on their hard drive and it print out. He wondered about making an accompanying app, but it required players to have a second device to hand and would lead to him having to make it. Ultimately, he looked within himself. “I think I would play it, but I think if in a bad mood I wouldn’t. So that kind of like made me think, no, this is a no-go.”

Chung didn’t leave the idea completely behind, though. He resolved to create the manual in the game itself, accessed by pressing tab. It would, he hoped, have the same flavour of being more detailed than it needed to be, kind of useless and fun.

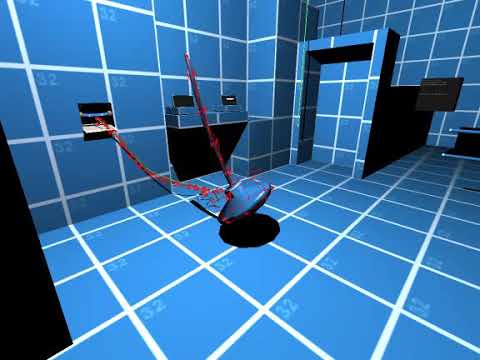

But then he changed the whole premise of the game. He started thinking about introducing the concept of traversing two worlds, the real one and a cyber one. In order to access the cyber world, the player would break into buildings to jack into access points, pulling a cord from the wall and plugging it into their deck. Once jacked in, their meatbag body would crumble to the floor while they explored the cyber world. “But the gag was that you had to defend your defenceless body at the same time from security guards and police patrols and things like that,” says Chung. Before jacking in, you’d set up defences with claymore mines and detectors, and you’d be able to program them to send messages while you’re in the cyber world warning you of impending danger to your meatbag.

“You’d have to make decisions - oh no, you have a timer on this heist, do you have time to go back to the real world and pull out your gun to shoot the bad guys? I thought there could be a cool push and pull between the two worlds, and you’d constantly have to figure out what the best, safest way to do something would be. I was really excited to do it. I thought there was something really juicy there.”

He’d never get a chance to make it. Two years into development on Quadrilateral Cowboy he realised that he’d bitten off rather more than he could chew. Look at the Blendo Games back catalogue and you’ll see how Chung tries out designing within different genres, from Atom Zombie Smasher’s take on the RTS to Flotilla’s take on turn-based space strategy. ”For this I thought, ‘I’ll try doing an immersive sim, I think that’ll be a fun genre to do.’ It’s really hard to do an immersive sim! I underestimated the amount of work and thought it’d require and the sheer quantity of things it demands from you. It was difficult to figure out how all the mechanics worked, how the heists would work, how the computer would interact with the objects in the world,” he says. “I was getting stuck into this hole of not being too sure of what the player was going to do.”

Chung realised that in order to be able to release the game he’d need to streamline or simplify it, and the campaign structure was going to take a hit. Rather than hold it in some non-linear world in which players could tackle the missions in any order, he decided that the missions would be entirely sequential - ‘no frills,’ as he describes it. “Once I’d made that choice, I felt a weight lift off my shoulders.”

One thing that became clear was that the linear missions needed a little extra something. “It feels weird to have a static world where nothing changes; there’s no arc or progression,” Chung says. So in the final year of development, Chung created Quadrilateral Cowboy’s storyline. Elegantly told, featuring the chance to visit the homes of the hacker crew and to witness their rise to success and the repercussions that follow, it replaced his original intention of a light premise which would allow players to make their own story within immersive sim-style emergent situations. And, with the help of this cut in the game’s ambitions, he finally released Quadrilateral Cowboy in the summer of 2016.

Sometimes, major things in games get cut. And, in fact, Chung had been through it all before when he was making Atom Zombie Smasher. This procedurally generated RTS was originally meant to have an XCOM-style management component in which players would set up bases, recruit scientists, transfer soldiers and procure equipment. But as release neared it simply wasn’t working, and Chung axed almost all of it. “And the game shipped and it did fine,” he says. No one detected that it was missing. “I knew and I had to live with it, but no one else did. The game stands on its own.”

As he struggled to figure out whether Quadrilateral Cowboy would betray having such a major part of it torn out, Chung thought back to that experience. “Trying to figure out whether a game stands on its own is a little more tricky than I thought it would be. I know all the things that got cut. Some people might think that was the game as it should be, but for me it’s like, well, it’s what it could have been, but this is what it actually is.” And what Quadrilateral Cowboy is is a great game, with a story that seems to blend effortlessly into its mission structure.

That said, it would be so fucking cool to play that open, book-accompanied version of itself.