Japanese PC doujin are keeping indie games creative at Tokyo Game Dungeon

Retro consoles, coke bottles, and deliberate glitches

To track the public understanding of modern-day indie gaming is to look at the small-scale independent development scene through an Anglo-centric lens. While it would be unfair to ignore the hobbyists programming experiences in BASIC on their ZX Spectrum or similar, it’s commonly accepted that indie gaming as we recognise it today has its roots in the early days of the internet and the Y2K boom, when Flash, Gamemaker Studio and similar tools allowed things like Cave Story and N to grow. With online distribution further helping games like Bastion, Journey and World Of Goo to flourish, the definition of the indie game became: a title with big ambitions and creativity grown from small budgets and teams.

It's not entirely wrong, but it has obscured decades of hobby development that was once at the forefront - not just the stories of BBC Micro solo-development stars, but similar ones of hobby development from around the world. In Japan, the doujin markets of Comiket and beyond serve as a home for hobbyists to make, sell and share their creations. It is the doujin gaming scene that helped major studios like Fate/ studio Type-Moon, and franchises like 07th Expansion and Touhou Project, flourish in a way that would never be possible otherwise.

Nowadays platforms like Steam make doujin games and indies more accessible than they ever were in the days of the Spectrum or MSX. No longer do you need to fly to Japan to access the latest works from the many creators who make up this community. It’s with this in mind that Tokyo’s latest doujin event, Tokyo Game Dungeon, held its second event in the heart of the Hamamatsucho business district, bringing everyone from professional indie teams to doujin circles to mom-and-daughter duos into one place to share their craft and celebrate their passions.

Doujin games stand apart from indies in part by their purpose and definition. Whereas the indie market’s evolution has defined independent development in terms of the scale of production and inception away from the major studio model, doujin games in Japan define themselves by being unique experiments produced by and for like-minded fans. Burning a CD-ROM of your amateur project to sell at a doujin market is a right of passage. While most know doujin titles as esoteric ideas using characters from larger IPs (with questionable regard for copyright), it's a home of experimental oddball ideas in small-scale sandboxes that couldn’t exist otherwise. They won’t be the money-spinning masterpieces many studios can justify investing in, but they’re fun. And that matters.

January's Tokyo Game Dungeon followed its initial incarnation this past summer. While far from the scale of more well-known events like Comiket or the indie gaming halls of Bitsummit and Tokyo Game Show, this event was aiming to be something distinctly different: a small-scale event by and for the doujin scene, sharing work just because you can or, in some cases, because these quirky games can only be appreciated by a crowd of ‘your people’ - in this case around 1200 people, including exhibitors.

A number of established doujin circles (a group of like-minded fans creating content together) used Tokyo Game Dungeon as a space to showcase their past and future work. Zakuro Bento are a circle dedicated to creating adventure games and visual novels for women, and brought their latest title Romp Of Dump. A card game-based mystery set in a high-security prison for the worst offenders, it's created with Unity and brought to life with expressive animations using Live2D technology. It even incorporates Live2D to introduce a bluff and risk-reward mechanic to playing blackjack against your fellow jailmates, making it an impressive effort for the small team.

On the complete other end of the spectrum were titles like Rabbit Soft Worker’s 2019 release Lostword, an MSX Turbo-only typing RPG. Despite being highly inaccessible (it’s not ported to modern PCs, so an emulator or original hardware is a requirement), it’s a labor of love, with detailed pixel art, a randomly-generated map, a surprisingly-deep and a battle-system with magic, and more - all wrapped in a seemingly-simple exterior. Yet according to the man behind RSW, Ko-Usagi, it was just a lot of spare time plugged into a platform they loved while growing up that made them want to make the game, and overcoming the hurdles in both development and accessibility was a big appeal in creating it.

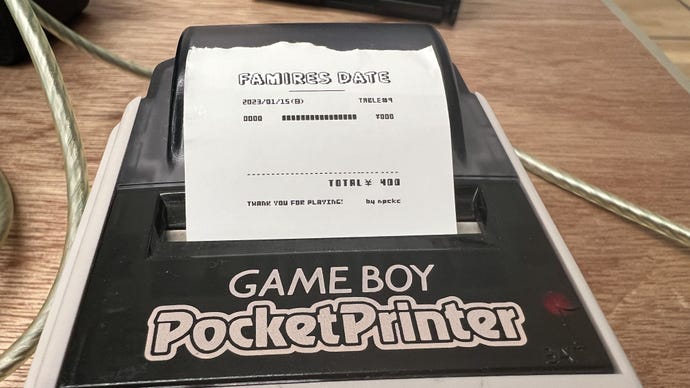

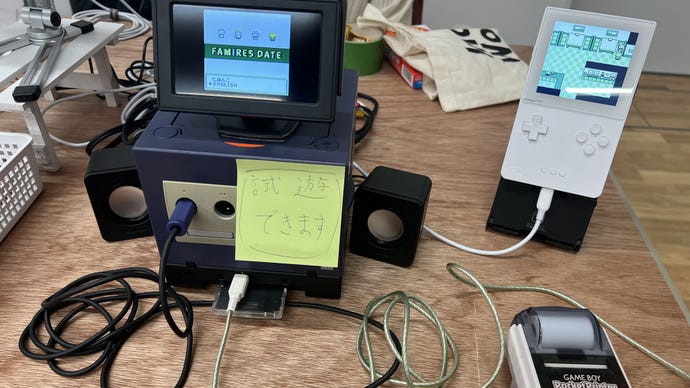

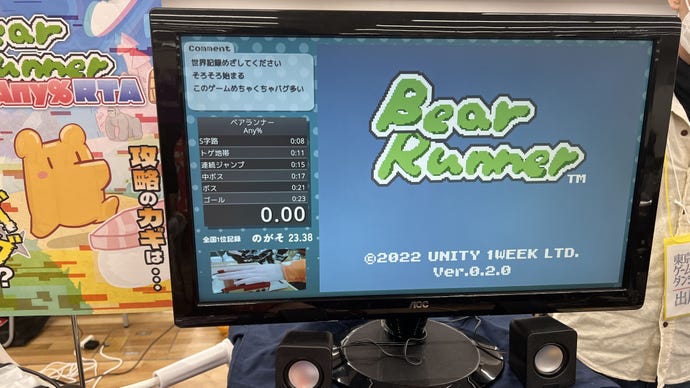

Perhaps capturing the experimental nature of the form were the many projects that can never be experienced outside of the walls of the convention hall - at least not in the same way. Many titles on display were developed for a communal experience. It's this tactility that brings to life projects like npckc’s Famires Date, all about handling a date on a budget, and which prints a real receipt using a Game Boy Printer at the end. Another game turned a used coke bottle into a rocket ship, shaking it as hard as possible in order to cause it to explode and fire into the air (with those scoring over 100,000 points receiving free chocolate), while Bear Runner Any% RTA modded a broken Famicom into a controller you smacked to ‘glitch’ a game and get the Any% record.

Then you have games like Make Friends, where the objective is as simple as its name suggests: make friends! But how do you do that? Obviously, you take a silicone head with a Vive motion controller inside and toss and turn it around in your hands to collect noses, eyes and mouths to create a face, before placing it onto mannequins on screen to create life. The results are as hilarious as they are horrifying, but it works. "I wanted to create something where the audience watching someone play it on a big screen is just as much fun as doing it yourself," explained developer Kumagoro.

A game like Touhou keeps its doujin roots by evolving through fan games, where anyone can take creator ZUN’s original characters into any project they like

But with so many examples, what does it mean to be a doujin game? You could argue the borders between indie and doujin have become blurred, and that there’s a risk of this labor of love disappearing, as the chance of greater commercial success reigns in creativity and fan-focus for something safer; something enjoyable yet ordinary. A game like Touhou keeps its doujin roots by evolving through fan games, where anyone can take creator ZUN’s original characters into any project they like (multiple of which found a home at Tokyo Game Dungeon). What other options do doujin games have in an increasingly-commercialised system?

I see that question answered in the charming simplicity of Jin Japan, a parent and child duo stumbling through their first Unity demo with the support of every creator at the event. Larger events inevitably push developers like these away, emphasising that they're industry events as opposed to community efforts, which in turn pushes away the community willing to support that journey. Teams like Jin Japan are a reminder of every creator’s origins, and the memory remained with me long after the event.

There’s a fear that doujin games becoming accessible via Steam, or a blossoming Japanese indie scene reaching for the spotlight once reserved for Western creative darlings, could cause the hobbyist origins of game development to die away. This fear is unwarranted, but wouldn’t it be a shame to lose the limitless possibilities doujin gaming can offer? Possibilities that exist either in spite or because of limitations, and a desire to build on the ideas of others? Still, I came away from Tokyo Game Dungeon with a renewed passion, having been reminded of the potential of games in the rough-yet-infectious excitement of the crowd. Doujin work is a community coming together to create and share, something that shone stronger at Tokyo Game Dungeon more than any other event.

It's perhaps summarised by Newfrontia Software’s shrine to popular VTuber Usada Pekora, and their story of requesting permission from Hololive to showcase their reskin of the streamer chat simulator Cool x Cool. Or maybe the moment when yuri doujin game circle Sukera Somero passionately detailed how the universal Esperanto language served as the basis for one of their works, as they left the doujin circles to attend a gaming event for the first time with Tokyo Game Dungeon. Or even that it was hard to talk to developers about the work of games - like the split-personality mystery adventure Detective Nekko, an exciting mystery with an anthropomorphic animal cast - because they couldn't stop telling me how amazing everyone else’s games were! Or maybe it was the signed whiteboard complete with the signatures and doodles of all the exhibitors, a commemoration of the day that was filled with their love of simply sharing a room together?

With so many individuals from all walks of life creating cool experiences, for no reason but that they want to do it, I doubt the pioneering, free-range spirit of doujin gaming is going anywhere anytime soon. It’s about creating something because you can, and regardless of whatever stands in your way, just to bring a smile to another player’s face. It’s an attitude that has drove the doujin scene for decades and helped reshape the industry in Japan, as titles like Touhou reshaped the relationship between game and fan, or brought mega-hit franchises like Fate/ into existence. And it’s a spirit which shone brightly at Tokyo Game Dungeon. Long may it continue.