Premature Evaluation: Levelhead

Does a robot even know what it means to jump?

Shigeru Miyamoto is one of the few bona fide, mega-brain geniuses working in games. Inspired by the time he watched a plumber die of a concussion near a tortoise, the Nintendo luminary invented Mario in his toolshed in Kyoto, using nothing more than a couple of AAA batteries and a soldering iron.

He’s also an undisputed master of instructive level design. Whenever you see a door that’s slightly more illuminated than the other doors in the room, subtly indicating that this is the only door in the corridor that your character can open, you can trace a line of inspiration all the way back to Miyamoto. Whenever you see a broken ladder in the corner of an abandoned orphanage, implicitly prompting you to look upwards into the rafters to see a scary ghost, give thanks to our lord and saviour, inventor of goombas and jumping, the most beautiful mind in games, Miyamoto.

Level 1-1 of Super Mario Bros is regarded as a benchmark in teaching the uninitiated player the rules and mechanics of a game’s universe, without the use of the 500-page instruction manuals that typically shipped with platformers at the time. Every pixel is a lesson in how to play. The first encroaching goomba teaches you how to crush enemies under foot. Collectible coins trace the arcs of the jumps you’re required to make. The sudden appearance of a mushroom lets you know that, hey, things are pretty kooky here in Mario’s world, so strap yourself in.

This week’s Premature Evaluation is Levelhead, a gushing love letter to Mario’s brand of intuitive level design. More accurately, it’s a love letter to Super Mario Maker, the excellent Nintendo Switch platformer that allows players to create and share their own Mario levels with one another, and to briefly indulge in the arrogant fantasy that, if only they had access to the same tools, absolutely anyone is capable of being a Miyamoto.

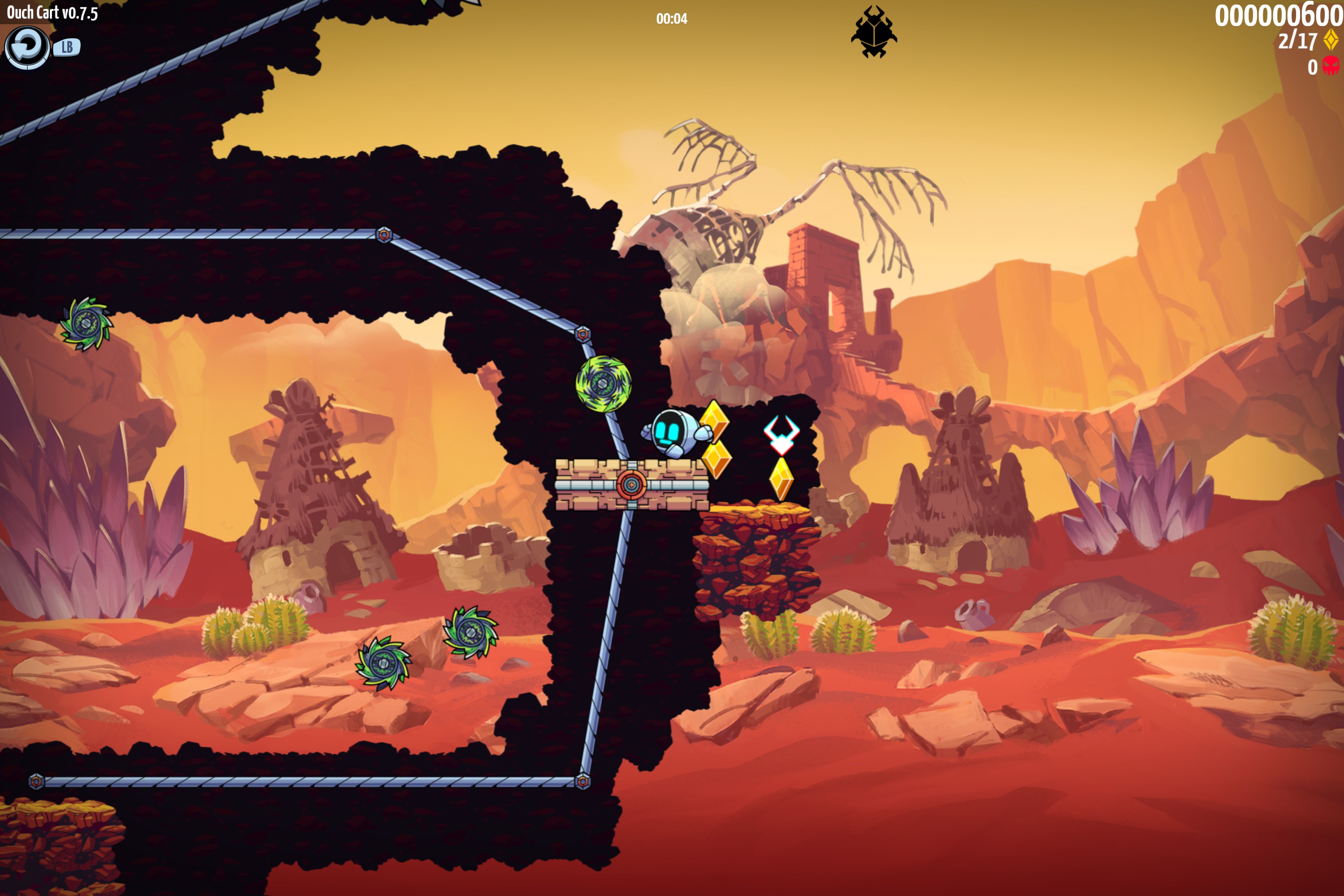

You play a cute little delivery robot, repeatedly catapulted into new levels to retrieve a crate and courier it safely to the exit. Along the way you’ll face a series of hazards and obstacles, spinning blades and spikes, flaming things and angry doodads to avoid. You’ve got an extending arm, which can be launched in any direction to grab objects and lug them around with you. Crates can be dropped on pressure pads to open gates, keys can be chucked at doors to unlock them – there aren’t many surprises to be found here, but that’s not to say it isn’t delightful and inventive at every turn.

Levelhead is refreshingly cartoonish, bright and primary coloured, and wears its Nintendo influences on its sleeve. Rather than sliding down a flagpole to finish a level, you’re aiming to hit a vertical tractor beam at as high a point as you can reach. Donkey Kong Country style roving barrels will launch your little robot guy to new areas of the level. Super Mario Bros 3 style power-ups will grant you new abilities, such as being able to cling to walls like Spider-Man, teleport a brief distance or jetpack over large gaps. One particular level, in which you’re fleeing a spinning saw blade on a floating platform, is so similar to one in Super Mario World that somewhere a sleeping lawyer will have sat bolt upright in a cold sweat, somehow suddenly aware that something had just been infringed.

It’s incredibly good fun, and adds more than enough of its own ideas into the mix to move past being a straight up imitation, with an intuitive style of platforming that’s as much on a par with Meatboy as it is with Mario. Like any good platformer, the physics of it are simple enough to get to grips with, but leave enough headroom for mastering the controls, with hidden areas and just out of reach gems encouraging you to explore at the edge of your abilities. And after each death, the instant restarts at your most recent checkpoint prevent there being any reasonable point during play at which you might decide to stop playing, so you just keep going until you’re sufficiently hungry, thirsty or tired to stop.

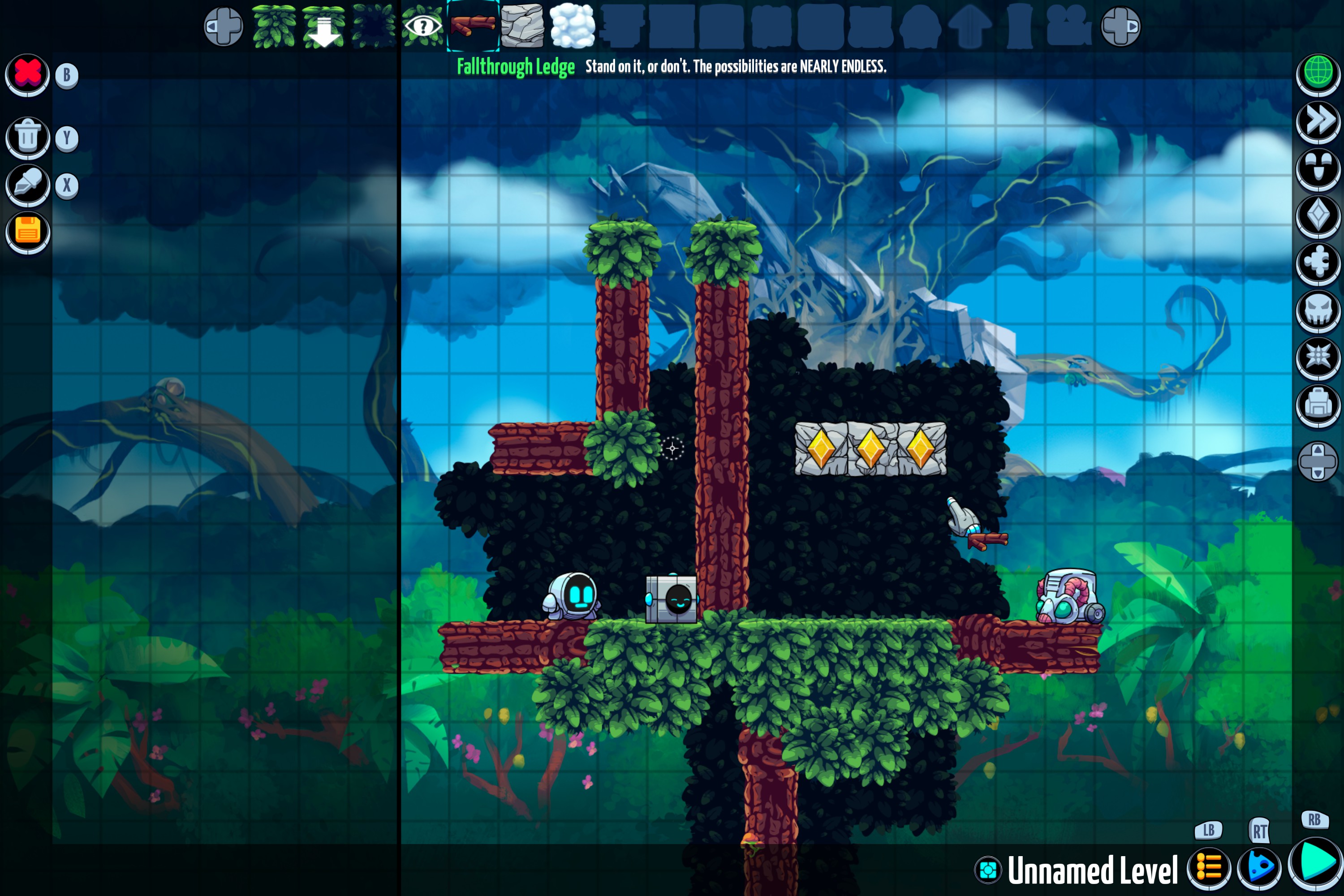

As with Super Mario Maker, a lengthy campaign mode takes you through a generous set of developer-designed levels, which readily demonstrate all of the various blocks and elements that comprise the level editor’s toolbox, and then gradually unlocks them for use in your own levels as you play. The level editor is deeply intuitive, a what-you-see-is-what-you-get type deal that lets you plonk down tiles on to a grid, and then instantly jump into and test your creation as you build it. The editor is a marvel of design all by itself, polished, satisfyingly animated and entertainingly written. It rewards experimentation, encouraging you to submit and publish your creations, and empowering a huge and growing community of creators to design a seemingly never-ending series of madly challenging new levels.

If we're to draw any conclusions from this vast catalogue of amateur levels, it's that Levelhead's players are not budding Miyamotos, but inventive and talented sadists. The user-created cache of levels are almost entirely designed to test the skills of players who've exhausted the base game and found it to be too lenient with its spinning blades and flamethrowers.

But there are plenty of exceptions to this rule, where designers have taken unlikely elements of the main game and repurposed them to suit their own, very specific needs. I played one creation that used a sequence of teleporters to let you flip between two mirrored versions of the same level, and another that employed an impossibly complicated network of switches and gates to form a level that looped back on itself multiple times, reassembling itself on the fly with each subsequent lap. Another level used a series of cleverly positioned traps to create a gerry-rigged pacifist mode, where jumping on an enemy would cause the ceiling to give way, killing you instantly.

Scratch beneath the surface of its offering of user-created levels – a dynamic and curated ‘tower’ of new creations and a comprehensive search and filter function helps with this – and Levelhead is a spectacularly strange and varied thing. Much more than just a Super Mario Maker clone, it’s an impulsive and endearing platformer, drip-fed by a genius hoard of masochistic level designers.