More games should be truly honest about death

Do not go gentle

This article discusses death and personal bereavement

I never intended to make videogames about my brother. He died in May last year, standing in the crowded lobby of the Manchester Arena, at the hands of the radicalised young man who’d walked into the building and detonated a homemade explosive. I learned later, while numbly standing with a police officer in middle of the cavernous, shrapnel-damaged space, that he was standing approximately seven feet away from the bomber, and was killed instantly. His name was Martyn, and he was 29.

Going through something like that completely altered my trajectory as a person. But, over time, I realised that I’d quietly changed as an artist and games designer too -- everything I was working on had stopped, and games had unexpectedly become the outlet through which I began to process it all. With this came a changed perspective: that games should be depicting the honest reality of death, because it can be incredibly helpful when they do.

We have this societal taboo which means, understandably, that most people don’t like talking about the ins and outs of death. It’s a black box. It was for me anyway; I’d never even been to a funeral as an adult, I didn’t know what happens at one. Games are weird about death, too. They’re great at depicting a certain kind of death, but it’s a particular kind of pantomime demise. I’ve killed thousands of enemies in hundreds of videogames, and there’s an expected and specific manner in which people tend to die. Point and click to fire your assault rifle, and in a burst of red particles the person in front of you transforms from animated enemy to a curiously lightweight ragdoll, then ceases to exist. Videogames lie about how heavy a body is, too. I’ve effortlessly shifted plenty of floaty dead ragdoll people out of the way in games, but only carried one body in real life. It was difficult in every way that something can be.

It’s funny in a way, what videogames teach you. They might be terrible at talking about death, but they’re great at simulating the violence that usually precedes it. All the explosions, terrorists, unfathomable numbers of weapons, and a million other things that suddenly became part of my real life. In a grim sort of way, this baked-in videogame knowledge became almost the first way in which I was able to process what had happened to my brother. They didn’t teach me enough about the aftermath, though. I know more than I want to about what happened in that room, but I didn’t know much about what would happen afterwards - to him, or to me.

Some games are examining death in a different light. A Mortician’s Tale, That Dragon Cancer, Life Is Strange - you know the ones. These are the games I’ve been absorbing and revisiting since the attack, viewing them through an entirely different lens. In particular, A Mortician’s Tale has been revelatory. It places you into the role of a mortuary technician, and unflinchingly looks at not just the preparation and burial of bodies, but the tangled human stories that surround the death of a loved one: the loss, the regret, the conflict, the black humour.

I saw my brother’s coffin slide through the doors at the crematorium, and had no idea what happened after that. I was shown it explicitly in A Mortician’s Tale, and it was a difficult, weird, but immensely valuable thing to be taken through. Even through the understated, cartoonish visual style, the game delicately and sensitively filled in so many of the blanks in something we all inevitably go through. A few years ago I’d have regarded A Mortician’s Tale as a charming and slightly morbid indie curio and left it at that, but it now represents something far more powerful to me: an honesty, even if it’s an uncomfortable one.

A death can be extraordinarily complex. Handling it isn’t just about how, where and when a person died. There’s more to it. The death includes the people that surround the person, the context, our thoughts and feelings and regrets and loose ends and a million other tendrils of sadness and stress and confusion. Of course, as this was a terrorist attack, it came with even more complexity: journalists, politics, inquiries, exposure. We didn’t have the funeral for a long time. We weren’t allowed.

Creating videogames, quite unexpectedly, became the way in which I tried to make sense of some of this - or at the very least, the way I tried to get across to people what the tangled mess was like. As a player I’d been through so many narrative games that left a real imprint on me afterwards, and so it was logical, in a way, that I’d turn to these games to figure my own stuff out.

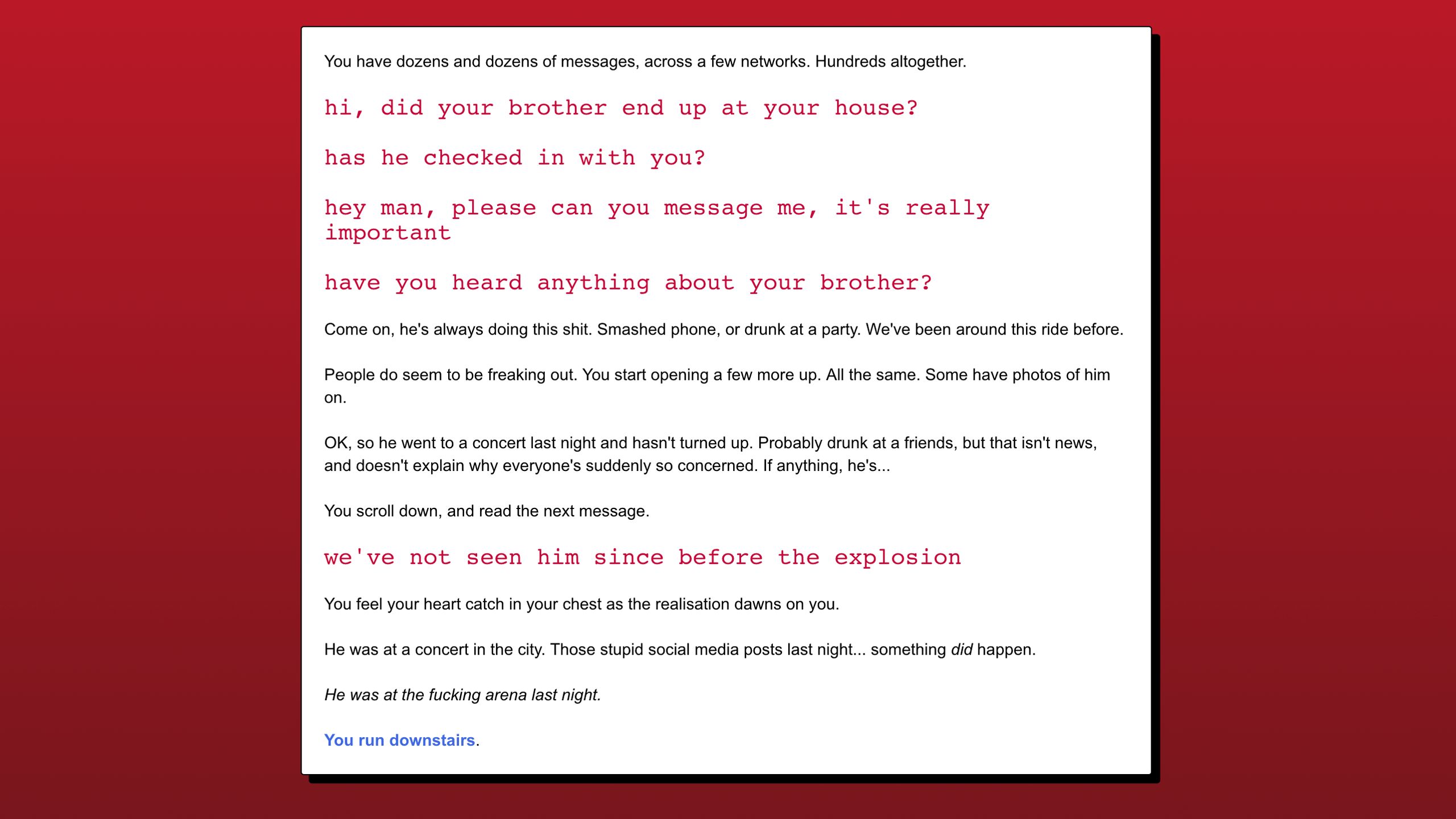

I’d been writing a lot, right from day one. These scrawls became a small interactive fiction game, c ya laterrrr. The name is taken verbatim from the last message my brother ever sent to me, a throwaway goodbye after a mundane online conversation. One of the hundreds of possible pathways through the game reflects my real journey through those days, but it isn’t shown to the player. It doesn’t matter: the game is really about the decisions I didn’t make. Later, I tried to tell the same story in a different way through The Loss Levels, an arcade cabinet commissioned for Now Play This. It forces players through fifteen rapid fragments of memory in the days after the bombing It’s relentless, unpredictable and confusing, reflecting what those intense few days were like.

These little games - prototypes really - let me show people, rather than having to tell them, what parts of this experience were like. A later game, Sorry To Bother You, depicts me using my mobile phone while being hounded by aggressive journalists. Players need to pick out and delete the thinly-veiled journalist requests hidden in the thousands of messages of condolence -- the real kicker being that every word in the game is completely real. In two minutes of intentionally unwinnable message filtering I could say more about press intrusion than I could in a whole novel of written words. Games allowed me to say: don’t just take my word for it, here.

As a player, I’ve begun to reassess the themes of the games I’ve been playing, too. I like blockbuster shooters as much as the next guy, but I’ve also been a long-time supporter of experimental games (I started the original MCRGameJam in Manchester a long time ago). I began to really re-examine so many of the leftfield games that were telling unconventional stories, their tales taking on new meaning to me as a player. These are often works by unseen and undervalued creators, or those expressing new or difficult stories. They can use the unique powers of videogames to get their experiences out there, to get themselves out there. Videogames like A Mortician’s Tale or That Dragon, Cancer aren’t just curios, they’re a critically important part of videogames culture, and are created by people that, for many reasons, are suddenly in need of a voice.

I’m now writing a much bigger game, Closed Hands, that pulls the camera away from me completely and uses interactive fiction to look at radicalisation and extremism from a wider, societal angle. Games are an incredible vehicle for exploring the most difficult of topics, but they’re themes that largely don’t exist in games right now.

I honestly believe that there’s room for everything within games. I’ve not hung up my assault rifle just yet. But I found genuine catharsis in making and playing videogames that deviate from safe themes to examine challenging subjects. Something as messy and complex as death has begun to make a least a little more sense.