RPS Exclusive: Warren Spector Interview

Just before Christmas, Eurogamer got me to travel up to Disney's London headquarters to interview Warren Spector. The resulting piece covered all the big matters of the day - Deus Ex 3, Portal's awesomeness and how when his new game is finally announced he'd be "vilified". But there was a hell of a lot more. Starting with polite small-talk, and extend outwards to take in his admiration and identification with Walt Disney, being "Tech's Bad Boy", how best to approach The Icons, putting his money where his mouth is, Being In a videogame, the importance of teaching videogames, creating an oral history of games, what it's like to be a 52-year old designer and JRPGs about Chopin.

The one thing we didn't ask him why he decided to hook up with this Mickey-Mouse outfit...

RPS: So, Warren. How are you?

Spector: I'm tired right now, that's for sure. And excited. The sad thing is that I can't talk about the project... but it's as much fun as I've had in a decade. It's definitely the kind of project which is going to polarise people, which is good for me...

RPS: Why does that excite you?

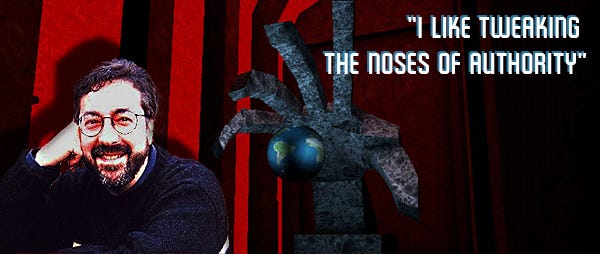

Spector: I think that I'm tech's badboy. I like tweaking the noses of authority or something, and like forcing people to confront the assumptions in their own lives in the same way which I like to make games that force them to question their assumptions about gameplay. It's fun to get people to think about why they like or don't like something.

RPS: Okay - as a general starting point of where you are today, can we talk about how you and Disney got together?

Spector: The shortest version is... well, I was out pitching an epic fantasy RPG. It was like Deus Ex and System Shock and the Ultima Games, in that it combined a bunch of genres... and there was one really, really interesting new innovative thing which I don't think anyone was doing at the time, and I still don't think anyone's doing. I'm out there pitching this thing. I get hooked up with Seamus Blackley, who's an agent at Creative Artists Agency [And prominent figure in the genesis of the XBox - Ed]. He represented me and my studio. He suggested we talk to Disney. "Talk to Disney? There's no way they're going to be interested in this!" "Oh, you don't know that - they're changing. Let's go out and talk to them." So I go out there and pitch this thing and... as we're talking, they start looking at their Blackberries.

RPS: Ouch.

Spector: "Okay - this didn't work. I was right. Seamus, why did you waste my time!" But it turns out they liked the pitch and what I was saying enough, I guess. They wanted me to talk about another project they needed to get done. They said they had another fantasy game - the Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe thing, and didn't - at that point, anyway - want another fantasy thing going on. "But would you be interested in doing a licensed game?" And I was: "GIVE ME CARL BARKS!" I want to do Uncle Scrooge Duck Adventures? Ohmygod! At the time, I had another pitch for something I called "Night stalker" as a working title, which Disney owns and were bringing it back as a series... so I said, I'd love to do a Night Stalker thing. But, they said, they had something in particular. They pitched it to me and I initially went - oh no, I'm not doing that. Then we got talking more, and they convinced me that they were serious about doing some really interesting things and were willing to give me a pretty horrifying amount of creative freedom. And the challenge was huge, so I said... I'll do it. We did four months of concept development as an independent. And then they said... we love your concept, but the way you get to do this game is we acquire you. So, I said, "no". They said, well, let's put something together, and we'll see. They put together a package, and it wasn't good enough and I said no. And they said... "We're Disney!" Well, sorry. So we went off and did a bunch of stuff with Valve and Vivendi.

And then Disney came back a year later and said... we love your concept. We've been looking for someone to do this project. Please, do it. I said... well, I do love this project. This time they put a package which was... just barely good enough. It's the opportunity of a lifetime - it's a dream project for me. Maybe not for anyone else, but it really isn't an opportunity which doesn't come along every day. So we did the deal.

RPS: People are generally quite surprised by what someone in the position of creative power chooses to do next next, when abstractly they could do anything. Look what Peter Jackson. Post-Lord of the Rings, he was in the position to do anything he wanted to... and he does King Kong. Is it almost like that?

Spector: Well, I hope I'll be more successful.

RPS: Well, yeah.

Spector: It is kinda like that. I've said this over and over, but it's not like I'm wearing a Mickey Mouse T-shirt and a watch because I'm working for Disney. I have the mouse ears I got when I was five years old. I have the Mickey and The Beanstalk 78 RPM records my mom used to play for me when I was a kid. I was the 3000th person through the turnstiles at Disneyland at its 30th anniversary in 1985, and won a prize. I was Mr 3000 for the day! Working for Disney is one of the things I'd wanted to do. I really did talk to the folk at Imagineering in 1988 about being an Imagineer. Even if this ends up being a disaster... I wanted to do this all my life. Relax. You know, my motto is "Fail Gloriously". If this fails gloriously, it fails. Failure is fun.

RPS: There was that controversial speech you made a few years ago about working with licensed properties. This is you putting your money where your mouth is, yes?

Spector: Exactly! That was exactly what I said when they asked me whether I'd be interested in doing a licensed game. Yeah! I've been waiting for the opportunity for years. I gotta show all these nimrods they're just full of it. "I can't be creative doing a whatever game!" Come on! Of course you can. Find the spark of creativity, the thing which makes the licence works, find a way to translate that into a new medium... how can you notfind that an interesting challenge? Even if you're working with the most ridiculous bastards on the licencing side. Find that spark, find that one thing. For better or worse, this is me putting my money where my mouth is.

RPS: Now, we can't talk about the game, I know, but you've actually been hands on with something this big before, yeah? This level of playing with icons...

Spector: It's safe to say that I wouldn't have been tempted if weren't something big and iconic which everyone would recognise.

RPS: Hypothetically, if you're working on a major icon, how do you approach that? You talk about cutting something to the core - how do you identify that?

Spector: I think everybody's approach will be different. My approach is very research-orientated. I have to immerse myself in something. There's a little bit of an autistic thing going on. In Deus Ex, I delved so far into the world of conspiracy and Nanotechnology and stuff... I have a vast library of books about those things. It's the same thing. I have to go in and watch every Disney feature film, every Disney cartoon, dive into the archives - it's been so cool that I've got to hang out in the Imagineering archives. The props library is incredible. I'm not saying I'm right, but you have to go and immerse yourself in something until you understand it as well as the people who created it... and then you ask, what's the core? What's the challenge? What's the problem with this? What can I do here that no one's ever done before with this world or character? But you have to understand it inside out before you even get to that point.

RPS: When you hear people writing comics for Marvel or DC, one of the phrases they use is "playing in their toybox". Is that what you feel like?

Spector: Absolutely. This is... heh... the moment I should keep my mouth shut. I've always related to Walt Disney on a deep and personal level. I would never say I had that kind of talent, or ever have that kind of impact on the world, but I read biographies of Walt Disney, and though biographies are completely different, the things which motivate and drove him, I totally get it. And so the opportunity to play in his toybox specifically... that's the cool thing for me. When you're dealing with something big and iconic and unnameable and unknown... something like that is going to touch all parts of the organisation. Graham Hopper who runs Disney Interactive suggested we create a steering committee that would bring in people from all parts of Disney. Our producer, Rob Rowe, over at Disney Interactive, pulls all these elements together. I'm sitting in a room with a couple of the most senior guys at Disney feature animations - guys I know by name, and now I know them. Artists I've admired for 40 years. We're sitting in a room, and they're doing concept art for us. Creative directors from Disney Consumer Products. Imagineers. People from Pixar. That's the sandbox we're playing in. I can't imagine anyone not being excited by that.

RPS: This is going to be a game that's primarily aimed at people who don't know who Warren Spector is, isn't it?

Spector: I think to succeed at this point, given the cost of making a game, and given the competition, I think that every game has to appeal to people who don't know who Warren Spector or Will Wright or... again, I'm not putting myself in that category. I describe myself as the bargain basement Will Wright, the Wal-Mart version of Peter Molyneux. But none of us are a big enough game to sell enough copies to justify the cost. We started to feel that a little bit on Invisible War and Thief: Deadly Shadows. The cost was high enough that we couldn't - we couldn't - make the game for the hardcore gamers. There just weren't enough. And that was a big challenge, and I don't think we did very well with it. But working with Disney properties, with Disney's marketing might behind it - the property and the Disney name are going to be bigger than anything at Junction Point. It's probably a good thing.

RPS: With something like Invisible War, you had to deal with people's expectations of it. But there's going to be very different expectations with a Disney game, so you don't have to get around to what people are thinking. That's got to be an advantage...

Spector: I kind of embrace the entertaining for families that's at the heart of what Disney does. I haven't in the past. I've very much made games for me and M-rated games for people 18 and up. The interesting challenge - one of the things which Disney is looking for me to do - is help them reach an older audience. For them, an older audience is 13-24 year olds. And for me it's... how can I reach an audience that young? There's challenges each way. For me, I've got to work out how not to alienate all the people who do appreciate that kind of stuff, while not scaring off the Disney folk. We'll see. And that's the fun bit. If it was predictable, why do it?

RPS: Something I say to people: the problem with games is that I like too many of them.

Spector: Wow. That's not my problem.

RPS: In other words, I can kind of appreciate every genre. I can see something of worth. But there should be more games - very popular games - which I can't see the merit in, which I despise which other people love. That's what a wide demographic means - that it's not all just for you anymore. That's why people get angry over SingStar or Lego Star Wars - it's not for them, and since once games all were, that scares them. I think the future of games is wider and more interesting. I'm fine with becoming a sub demographic rather than THE demographic.

Spector: Absolutely. I've made a bunch of M-rated games for guys who like shooters and RPGs. I'm going to take one and not that. I genuinely believe if people give it a chance, they'll find all sorts of amazing gameplay they'll really enjoy... but it's very much not the sort of stuff I've done up to now. But the next one? Who knows? It may be much more traditional. Give a guy a break! The interesting thing is, as an independent going out and pitching, I was struck by how typecast I'd become and how typecast the studio was before we even released a game. People just want more of what you've already done. There's a comfort factor there - this guy does this kind of thing and that guy does that kind of thing, and I understand that so I don't have to think. But you're going to have to think about this one.

RPS: You're a developer in his early fifties. It reminds me of one of Rossignol's standard positions - that most of the major figures in videogames are still alive. How many art forms can you say that about? We haven't seen the end of a career arc yet. We don't know what kind of games a 52 year old developer makes.

Spector: I really want to talk about this at GDC or somewhere. There's a great talk about the greying of the games medium... it's one of the reasons why, and I don't know if word's got across the pond to here yet, but I'm working with the university of Texas, particularly the senate of American history there, which is a research centre and archive, to create a videogame archive. It exists now. I'm donating many boxes of old paper design documents and concept art and marketing materials and beta disk and hardware. Next week I'm carting that stuff over, so they can catalogue it and make it available to researchers. I'm teaching a course at the university of Texas, where I've been inviting - well - gaming luminaries to talk to me for three hours, from the perspective of, "Hey - I've known you for 20 years, don't try to con me and let's talk about the stuff that typically doesn't get talked about." It's part of an oral history project - because we are all still alive. Well, not all of us - Dani Bunten's gone and a couple of others. But we're getting to the point where the pioneers are not going to be here forever. We need to get it recorded for future generations before it's lost, in the same way that lots of early film history is lost. Gone. Never known. I don't want that to happen to us, as I really believe that videogames are the medium of the 21st century, in the same way that movies and TV were the medium of the 20th century. We have to preserve our history before it's gone.

RPS: The Internet makes us think that history will write itself. That all this stuff goes online, and is stored on something like Archive.org, meaning that it'll be there. But that's not true - there's so much stuff that isn't recorded there, and so much stuff which never works its way online.

Spector: It's kind of weird, but the first thing I talk to my guests in the class about. This is Monday night where I do the 3-hour interview - I always start out with biography. Because I've had 12 guests, and all but one of them said, "No one ever asked me that stuff before. No one's ever been interested in who my parents were and what my education was and how that impacted me as a developer, and when I discovered games and how playing chess with my dad was the seminal moment or when I discovered D&D in 1974." No one ever asks them about that. Because there's very specific things... except, when I come over here, when you guys all ask smart questions. I swear to god, I'm not saying that. You get asked the same questions, over and over and over again, game after game after game. The only person who has been asked about his biography, is Richard Garriott. And I swear he's changing the details of all of his stories every time he tells them, just to have fun.

RPS: He's videogames' Bob Dylan, I reckon. He's successfully manufactured a myth.

Spector: Yes, it's true! I've known that guy for 20 years, and I've heard him say that the Lord British name came from his D&D group. That at High School a bunch of upper classmen were giving nicknames to the new kids. I've heard him tell it was a summer computer camp where they knocked on his bunk door, and said, "You sound you've got a British accent!" I don't know which is true anymore. He really is creating myths. It's wild.

RPS: The thing for me, is that he's one of the first guys who literally put his personality in the game - in a literal way, as he put his PERSONNA in the game. I suppose that's why people ask him about it, as it's there. Where the hell did that come from Richard? Actually... talking about that, what was it like being in a videogame? I was playing Martian Dreams on a random urge... and suddenly Dr Spektor walks in the door.

Spector: Ah, in Savage Empire I was the evil Dr Spektor and redeemed myself in Martian Dreams. I wrote the initial concept document [for Savage Empire] and handed it off to another team, who made me the villain, dammit. Then, in Martian Dreams, which was my game, I got to make myself the no-longer-evil-Dr-Spektor, the Avatar's friend. I trademarked that. It's weird - it's very strange. I still get e-mails from people about that who are playing the game. When it came out - oh my God - we debuted it at CES... and I'm going to stereotype horribly here, but every Japanese person who came by had to take my picture with my arm around the monitor, because we had an image from the game up there. And... oh God. That's my main memory. But there's a couple of guys - Alec Jacobson is my nephew, who's been in a bunch of my paper-game stuff and was in Deus Ex. Walter Simmons is one of my best friends. Gilda Ginsel, his wife, is a character in Reap The Whirlwind - a Marvel superhero adventure my wife and I wrote together years ago. I feel kind of guilty that all my friends and family are trademarks of TSR or Marvel I don't know.

RPS: Could you talk a bit more about your teaching? Because that's your background, basically.

Spector: I was working on my doctorate in communication, I guess. I was going to teach kids to watch and make movies, I guess. I enjoy it. And games education is really important, in the sense that as teams get bigger and the projects get bigger it becomes much more damaging that every developer has a different vocabulary for discussing games and what they do. If I went to Valve and talked about scupping the code no-one would know what I was talking about. When we started working with Valve on some concept stuff, they started talking about orange maps. And what the hell's an orange map? At EA, what they call a producer, is what every other place I've worked for call a project director. And they call a development director is what everyone else calls a producer. The fact we don't have a consistent vocabulary is insane, and it's one of the things which education can provide. I've said this before, but every RTF-rated film graduate knows what an F-stop is, what a Keyline is and why you'd use it, knows what a fill-line and what cross-cutting and parallel action and a Dutch tilt is, and the difference between a pan and a tilt and a zoom and a dolly. There's this baseline of information which game developers need to have when they come into a situation, which they don't have. And we need so many more bodies now. We don't have the time to train, so they need to get that training some other place - and it happens in schools. On top of that, and one of the things we've discovered - and this is me being utterly cynical - in the US at least, the education system is less about educating students than making money. It's just horrifying. The reality is, videogame studies have become so popular that it'll make a lot of money for universities. So I get what I want - which is a larger talent pool from which to draw with a consistent baseline of knowledge, and universities get more students, which means they make more money which means they're happy. Which his kind of a win for everybody. And all I'm trying to do is provide a professional look at things. Sadly, the games education movement is kind of in its infancy. Most of the people in it are either people who can't get jobs, and if they could, they would - or they're people who love games, but don't really have any professional experience. I was just trying to bring a little more professionalism in.

RPS: I think that's interesting - Tim Edwards at PCG did an article on the state of UK games education a few years ago. He started off just interested, and ended up horrified at how unqualified so many people were. There were great courses, but some definitely were distinctly chancery. I remember a few years ago, a guy mailed me saying he'd got a job as a lecturer, and could I mail him some ideas for books he should read. I couldn't believe it. Dude! These people have paid a lot of money for you to teach them. It's like the Wild West.

Spector: Yeah, but that'll change. It's like Film Studies in 1960. There were two universities in the US teaching film studies at that point - USC and UCLA and maybe NYU was just starting. There was one book, basically. Lewis Jacobs' rise of the American film. Andrew Sarris was about to write The American Cinema. And someone needs to write the equivalent of that book for games. But it was the Wild West for them, and it'll change. There's already people. I can't really speak for the UK, as I don't know the European scene quite as well, but Carnegie Melon and USC are doing a really good job right now. Guild Hall at Southern Methodist University. Digi-Pen are doing a pretty good job. There are places you can go and look and... that guy gets it. That woman gets it. That programmer gets it. And that's way better than we were five years ago.

RPS: Moving back to something I've just remembered about Bioshock. It's got one of the highest Metacritic scores of the year - Halo 3 and Super Mario are two of the other ones. And there's been no backlash for either one - and that's because people knew what they were expecting, and they got what they were expecting. No one's going to come to Mario and critique it for its ridiculous plot, because they weren't expecting one. Making a new thing is the hardest thing in the world.

[And, yes, this was the same day I was writing Bioshock: A Defence for EG]

Spector: And something else that's really important... we have these rules of role-playing we applied to Deus Ex. And I have other rules... one of the more general ones, which applies to every game, is never throw a player's expectations. You're right- Mario Galaxy and Halo 3 never throw player expectation. They give an incredibly well executed version of exactly what you want. And BioShock, because it's operating in a different world - the old Looking Glass, Origin, Bioware, Lionhead world - where we're still trying to figure out what the hell we're doing. I won't speak ill of any other game - unless I really get stupid, which I've been on to do.... but Halo 3, and Halo in general, has always been a really well executed traditional shooter. And the Mario games... hell, I've got my DS with me, and I've still got Mario games on me. Everyone knows what they are and you better deliver on that. But what is BioShock? We used to call the immersive sims, but there isn't even a word for it any more. What is that game?

RPS: Okay, where do you see games generally at the moment? It's a big general question. We're halfway through a generation. PCs sales are down, but revenue streams aren't discussed. Where IS gaming?

Spector: What freaks me out right now is... we're in this little golden age. Age is too big a word. We're in a golden Christmas season. If you'd asked me that six months ago, it'd be doom and gloom and disaster, there's nothing. I don't even see anything on the horizon. But all of a sudden, we have Rock Band and Call of Duty 4 which is a pretty interesting game, we have Mario Galaxy, we have Mass Effect, we possibly have the resurrection of the adventure with the Lucas game I can never remember the name of - but the point is, there's all these really interesting games out there. We have two Nintendo platforms that force you to think differently about design. They force you. You cannot make a traditional game on the DS. Well, you can but it's foolish. I'm desperate to make a Wii and DS game. Right this minute, I just see so many people doing so many interesting things and there's so many games worth playing. There's a new Zelda for crying out loud! There's a new Ratchet & Clank! There's a lot of really good games out there.

RPS: It kind of morphed from a Meh year into one of the best years ever.

Spector: It might be. It might be.

RPS: I'm stuck - there's so many games I have to play, or want to play, so much stuff doesn't get attention.

Spector: I warned everybody. My last class met on Monday night. Other than dealing with final presentations and grades, I don't have to think about the class anymore. I warned everybody on my team - that every night, I'm going home and playing games. Weekends - I'm not thinking about work. You're on your own. I'm playing games. For a while, anyway. There's too much piling up. Eternal Sonata has music gameplay!

RPS: Fascinating plot too. [JRPG about Chopin dreaming. No, really.]

Spector: There's a ton of stuff out there... and I'm well behind.

RPS: The ocean game - Endless Ocean? It's a Jacques Cousteau 'em up. You stroke the fish. My girlfriend plays it, and she finds it very relaxing. Stroking the enormous whale. Great!

Spector: Oh, I've got to play that.

At which point we segue into the material in the original Eurogamer piece. As further information emerges about whatever Spector's up to at Disney, we'll let you know. And Thanks to Warren for his time.