The Manor Lords publisher thinks we should all reject the "opportunistic and predatory" quest for a viral hit

A chat with Hooded Horse CEO Tim Bender about strategy games and letting devs cook

If you're a strategy game aficionado who has yet to cast a monocled eye over Hooded Horse's catalogue, 1) which map hexagon have you been skulking under? And 2) you're in for a treat. Founded in 2019 with the signing of Terra Invicta, and led by Dallas, Texas-based chief executive officer Tim Bender and chief financial officer Snow Rui, Hooded Horse have spent the past five years grabbing up original strategy games and strategy RPGs like a smaller civ quietly steamrolling bandit fiefdoms, while larger empires like Creative Assembly and Paradox Interactive bleed each other white in the centre.

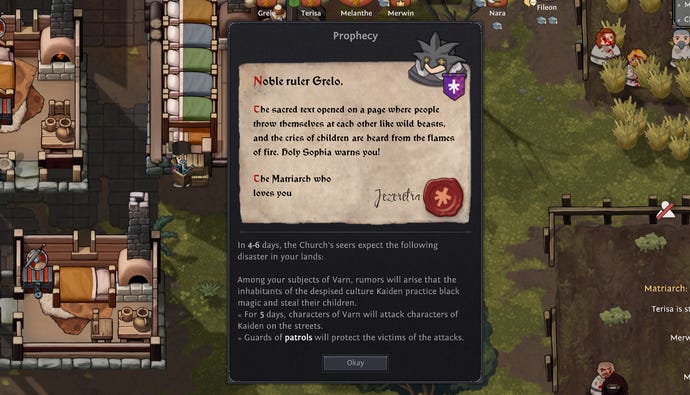

Which makes Hooded Horse sound like they're driven by competitiveness, whereas this is one of the few publishers that I would wincingly suggest are driven by love of the subject matter, because only a publisher that really loves strategy would scoop up anything as particular as Manor Lords, in which the oxen are far more lifelike than any fictional oxen need to be, or Nebulous: Fleet Command, aka Homeworld but you can program your own missiles. Or Falling Frontier, with its hypnotic, radar-blocking planetary shadows, or Norland, in which you'll want to be on good terms with the prophets.

I don't love all of Hooded Horse's games - I bounced off Ollie's cherished Against The Storm, despite obsessing over the premise, because the game's animal workers seemed too robotic in their behaviour - but I'm always eager to write about them, because they are so thoroughly their own worlds. The distinctiveness and variety of Hooded Horse's offering says a lot about Bender and Rui's feelings of "obligation" towards specific populations of extra-nerdy developers and players, and their guiding anger about how other publishers do business.

"I think that the fundamental principle that we're looking for, in terms of strategy games, is something that offers a unique experience, that a certain group of players will love, and how big that group of players is isn't so important," Bender told me earlier this year, shortly after Manor Lords became Steam's day-one most-played city building sim. "As long as it's something that will be truly loved by a group."

The strategy genre is, he feels, especially amenable to this focus on niche enthusiasts, because strategy games tend to be sandboxes, encouraging you to match up the pieces in florid ways - which makes their players more inclined to seek out imaginative spins on the fundamentals. "The players so often like to play multiple games, and like to interact with new systems, and, you know, they'll happily say, oh, I want to buy this indie game, to try out this experience of it. And then this other one to have a different experience. They value the creativity - they want new approaches."

Even in the wake of Manor Lords's thunderous launch, Bender is more enthused about the breadth of Hooded Horse's portfolio than the fortunes of any specific title. He and Rui would rather their company be remembered for helping a community of genre obsessives prosper together, than for one of those developers becoming the next Blizzard. Nor will they be plunging the money from Manor Lords into a massive operational expansion (at the time of writing, Hooded Horse have around 20 people on the books). Going public? By the sounds of it, that won't happen while Bender and Rui are in charge.

The past few years haven't made a great case for the wisdom of rapid expansion, nor placing your company's fate in the hands of public shareholders, but Hooded Horse have always defined themselves against such things. When I asked Bender whether publishing so many idiosyncratic projects has made Hooded Horse more "sustainable", he flipped the question.

"Sustainability is something we think about a lot," Bender began. "But usually we think about it in relation to developers. So we're in an interesting situation - we never took money from, like, venture capitalists, or private equity, or international conglomerates, or anything that would put pressure on us. In fact, we even wrote into our bylaws that we can prioritise other things over profits, like artistic integrity and fair treatment.

"And we're just owned by individuals - a majority of shares are owned by myself and Snow, together as husband and wife. And the other shareholders are smaller groups, individuals too, and many of them are in games. If not, they love games. And no one's really like 'when are the profits coming, endless growth', stuff like that. We're never going to go public, we're never going to IPO, we're never going to have any of that stuff that causes headaches for everyone.

"And because of that, we don't really have any perpetual growth goal. And we don't have pressure financially. And we've been lucky enough to work with such great developers, and they produce such great games. Even before Manor Lords, we were fully sustainable financially, based on the wonderful games those developers have made.

"And so as a consequence, we don't have to worry about sustainability, I think. But we're very focused on what's more important, which is developer sustainability. Because there are [publishing agreements] where the publisher gets all the revenue at first until they recoup their investment, and only then does developer start to get any share. That's very common in the industry. And we from the beginning, didn't want to do that - our preferred arrangement is just flat percentage splits."

For context, in March last year, Bender and Rui told MCV that Hooded Horse offer developers 65% of revenue, with the publisher's share covering things like localisation and marketing. This is open to negotiation, however.

"The reason for that is because of sustainability for developers," Bender went on. "Because games will have varying results, and if one game does a little worse, like you just said in your question, it's actually OK for us, because we've got a tonne of games. And that's always true of publishers, right? Publishers have like 10 games, they're diversified - one can go a little badly, one can go a little better, the two cancel out there.

"But for developers, that's like the end. And if they're under recoup, it's often the complete end, because if they're under recoup, it might be that if the game does a little worse, and there was some money spent on it, and now the publisher gets to take back whatever they put in before the developer gets $1, and that could mean developers not getting paid, and certainly not having the cash after release to keep staff around, to avoid layoffs, to continue developing and improving the game, and help it recover from whatever stumble happened at launch."

Bender feels that many publishers approach publishing like venture capitalist firms, backing a series of games in the hope of a hit, though he doesn't name any names. "They're like mini-VCs, where it's something like, 'oh, I'll just invest in five projects and four will flop, but one will go big, and I'll make my money there'," he explained. "And it's just a horrible way to think about things, right? It's opportunistic and predatory. People are trusting you with their lives and dreams, they're trusting you with the future of their studio and their employees."

Bender thinks players should actively seek out publishers that "take care of all the devs, especially the ones that might be struggling". To frame that in hard numbers, he says Hooded Horse tend to prioritise median revenue across their portfolio - median being the "middle value" separating the lower and higher halves of a series of figures - because median revenue can paint a clearer picture of the fortunes of the games in question, compared to either total or average publisher revenue, which may be distorted by games that sell a lot more copies. If you'd like to explore this further, hobbyist site Gamalytic keeps track of publisher median revenue and has been endorsed by a few game developers I follow, though I can't myself speak to the accuracy of their figures.

"What you do for the median game, and what you do for the game that struggled the most, and how you're trying to come back, how you continue to put your efforts into all your games fairly, and live up to the obligations of what you promised those developers, when they trusted their game to you - that means so much more, in terms of whether players should trust a publisher and say, 'oh, I'll try their next game'," Bender said. "That shouldn't be based on the viral hit. And whether a developer who's considering a publisher should trust that publisher, because don't bank on being the next viral hit."

Hooded Horse's rising-tide-lifts-all-boats ethic seems ideal for early access strategy games that may need more leeway from the publisher to coalesce and build a following, by virtue of the complexity of their player systems. Bender has proven pretty zealous on this count. Earlier this week, he and Hinterlands CEO Raphael van Lierop got into it a little on LinkedIn over whether Manor Lords has received enough updates since launch. Van Lierop opined that Hooded Horse and developer Greg Styczeń should have planned some more significant additions to Manor Lords (which he otherwise likes) in the months after release, to keep player counts high, describing this as "a pretty interesting case-study in the pitfalls of Early Access development".

Bender replied that, on the contrary, he had actively told Styczeń to ignore complaints about the shortage of updates, insisting that "success should not create an ever raising bar of new growth expectations" at the expense of developer wellbeing. Following an online backlash which has spread to other members of Hinterlands, Van Lierop has apologised for his post, commenting that "I should have found a better way to frame my original feedback, without referencing a specific game" and reiterating that he is "firmly pro-developer, and anti-crunch". I personally would love to hear the two CEOs discuss the subject more calmly. Notwithstanding Van Lierop's thoughts about the importance of swift updating, Hinterlands's 2017-launched The Long Dark - whose opening screen message includes a disavowal of crunch - is a prominent example of an early access project gestating at its own rate so as not to overwork the developers.

The one serious caveat I'd lodge about Hooded Horse right now is the familiar line that it's easier to promise the world when times are good. In the MCV piece above, Bender concedes that if Hooded Horse were up against it, the company would take on more outside investment, with all this might entail in terms of creative control and the company's ability to sustain that community of niche developers. "If it's between that, or not being able to fund games that need funding in terms of support and jobs, we would accept the money and then we would have to pay a price," he told the site. Here's hoping it never comes to that, because for this on-and-off-again strategy nut, watching Hooded Horse paint the map has been a source of slow delight.