"They don’t care": Inside the triumphs and failures of accessible gaming hardware

How custom and adaptive controllers serve players with disabilities – and how steep costs and bad attitudes threaten the good they can do

Malenia, Blade of Miquella, is a menace. Even among Elden Ring’s cast of bastard-hard bosses, the Goddess of Rot distinguishes herself as an ender of lives, a relentless steel tempest that has shredded the most prepared and dextrous of adventurers. She’s also been beaten, rather soundly, by a man using only his mouth.

Or, to be more precise, a QuadStick FPS, a specialised game controller comprised of a mouth-operated joystick and several 'sip and puff' switches. It’s the favoured tool of professional streamer and Guinness World Record holder Rocky "RockyNoHands" Stoutenburgh, who in 2022 used it to become the first quadriplegic Elden Ring player to claim Malenia’s scalp. This was a win for a QuadStick as well: a showcase of how adaptive hardware and clever controller design could make games more accessible than ever, enabling players with disabilities to match and exceed the heroics of their able-bodied peers. And yet, there’s little sense – among disabled players, advocacy groups, or even controller manufacturers – that accessible hardware is entering its golden age. While major breakthroughs have been made, high prices and commercial concerns still carry the threat of willing, eager players being left behind.

That’s in spite of, to the credit of hardware makers, a considerable expansion in the range of accessible controllers and control aids. The QuadStick FPS is in fact the latest (and most advanced) in a series of QuadStick devices, and Microsoft have supported arguably the most recognisable accessible gaming device, the Xbox Adaptive Controller, since it launched in 2018. There’s also a Nintendo Switch equivalent in the Hori Flex, as well as the compact but customisable 8BitDo Lite SE controller, Sony’s PlayStation Access system, and the entirely eye-operated Eyegaze. There are purely software-based options too, like VoiceAttack, which translates voice commands into controls for games and other apps.

Many of these are recommended or even donated to players directly by organisations like AbleGamers, a US-based charity that provides tailored gaming setup services to disabled individuals. According to chief operating officer Steven Spohn, identifying and securing the right equipment is an essential step towards getting disabled players back in the saddle.

"When you have a mind that's willing but a body that's unable, the hardware is what allows you to bridge the gap between the ability and desire," he says. "Those people would desperately like to have a community to belong to, or hobbies to enjoy, or just to connect with the loved ones around them. Sometimes the hardware is what allows you to get into the video games before we can even start to assess whether a game is 'accessible,' or whether it has the features. The software side of things can always be amended by developers, but if I can't even get into the game itself to be able to play via the platform, then we're just not even starting."

Spohn himself knows well the value of play. As a baby he was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy, and while he’s bested his initial prognosis by four decades and counting, is still living with the condition’s effects. Nonetheless, he still plays and streams games regularly, and few are more clued-in on what hardware is out there for people with limited movement.

"It completely depends on what kinds of players with disabilities are asking about," he responds when I ask about AbleGamers’ go-to kit. "The QuadStick is great for paraplegic gamers, the Elite controller from Xbox is fantastic for anyone who has stamina challenges or may just need a configuration on the controller to be slightly different. The modular design, especially with the Elite controller, is phenomenal for that reason."

"There's a lot of different hardware options that we give out all the time. More often than not, it comes from things like adapters. Things like the Titan Two allow you to play using, say, a DualShock on your Xbox. Having the ability to use technology that was meant for one platform on all platforms tends to be one of our greatest tools."

Adaptability is a common theme amongst accessible hardware – an acknowledgement that the nature and severity of disabilities will vary enormously between players. An arm amputee, say, will need a different setup of buttons and sticks to something with limited muscle control in their fingers, so with devices like the Xbox Adaptive Controller, a customised collection of inputs can all plug into one multi-use unit.

Still, sometimes a more specialised controller is necessary. Just ask the Malenia slayer, Rocky Stoutenburgh, whose need for a completely hands- and feet-free control scheme has led to him owning every past and current version of the QuadStick.

"I would break them every day!" he says of the older, more fragile models, the exposed springs and messily coiled air tubes of which make clear their handbuilt nature. He’s been having more luck with the sturdier QuadStick FPS, in terms of both accidental destruction and gaming capability.

"I haven't found a game yet that I haven't been able to play, or get to a high level at," he tells me. “The easier games would be anything where you only really have to use WASD or, like, one analog stick to play. Since you only have one analog release [on the QuadStick FPS], you can't look and move around the same time. So any game like Elden Ring is pretty easy, because you lock onto the boss, so you really only have to use the movement, you don’t have to look around. Games like that are a little bit easier.”

It’s not plug-and-play: to handle business in the QuadStick FPS’ namesake shooters, Stoutenburgh must regularly tweak its control input profiles so that the puff/sip sensors perform the in-game actions he needs. But it works for him, and years of profile-tuning experience mean he can make adjustments to existing configurations rather than build them from scratch. His Elden Ring profile, for instance, was just a mildly reworked setup for Dark Souls.

The dark side of all this customisation and adaptability, however, is how the onus for making a game playable – even using controller hardware purpose-built for accessibility – usually falls on the person with disabilities. The one party, in other words, that was looking for help in the first place.

It’s an irony that isn’t lost on Spohn. "I think that, as a disabled person, you are one of the most ingenuitive people on the planet," he says. "By necessity, you have to learn how to adapt to society, whether you are someone who believes that people are disabled, or they are 'disabled' because they’re just a human living in a world that wasn't designed for them, it doesn't matter. At the end of the day, what does matter is that there are things I can't do because of my life circumstance."

"So I can't use a traditional PlayStation controller to go play the new God of War, right? One of my best friends in the world helped write the damn thing. And I would love to be able to go play it. [God of War Ragnarök writer] Alanah Pearce is one of my best friends, and I'd love to go play the game she helped write, that'd be awesome. But I can't, because I can't go play easily on PlayStation, I have to wait until things are on the computer. So there are barriers, like the fact that, you know, PlayStation would rather release things on the console and not allow it to come to PC at the same time, where I would be happy to give them their $80."

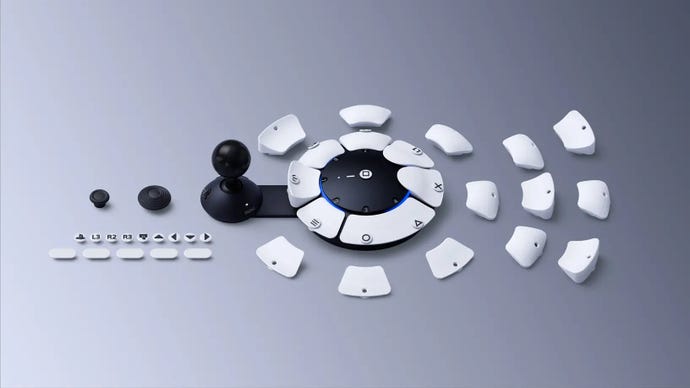

Sony revealed their own adaptive controller, the Access, last year. It forms a ring of large, fully interchangeable buttons attached to an adjustable joystick, all far easier for players with certain disabilities to poke and prod than the standard PS5 DualSense pad. However, when it releases this December, it will only be compatible with the PS5, severely limiting its usefulness to the disabled community.

Platform exclusivity isn’t the only barrier that needs clearing. According to Spohn, other players can and will argue against the use of hardware with accessibility benefits, either through bigoted malice or a mere misunderstanding of how the tech is really used. He points to recent controversies around the XIM Matrix, a USB adapter that allows for mice and keyboard input on consoles. That includes adaptive mice and keyboards configured for people with disabilities, but so-called "Ximming" is considered tantamount to cheating by some players, who see M+K controls as an inherently unfair advantage over gamepads. Destiny 2 developers Bungie have since threatened to ban players who use "third-party peripherals with the intent to manipulate the game client," while Overwatch 2 executive producer Jared Neuss has tweeted coyly of "interesting updates in the future" regarding PC peripheral use on consoles.

The worry among disabled players, like Spohn, is that employing such an adapter for legitimate accessibility reasons could result in them being booted from their favourite games. Bungie’s statement promises exceptions for "external accessibility aids," but the mechanisms for differentiating between disabled players and able-bodied "cheaters" are left all too vague.

In any event, narrow-mindedness looks to remain a problem for accessible hardware, even if the kit itself continues to improve. "Sometimes," as Spohn puts it, "it's just that people want to assume that people could only have nefarious intentions for using non-standard equipment."

Some big companies are getting involved with far more positive outcomes. Microsoft have done more than most for accessible gaming hardware, being the first major peripheral maker to launch a dedicated adaptive controller in the… Xbox Adaptive Controller. The XAC, as it’s affectionately known by the players and disability advocates who use it, looks like a set of toy turntables but is one of the most flexible gaming tools on the planet: its row of 19 3.5mm aux ports enables it to act as a hub for all manner of personalised buttons, switches, joysticks and D-pads. That’s 15 more than the PlayStation Access controller has, and unlike Sony’s effort, the XAC works natively on PC as well as Xbox consoles. It’ll connect to a PlayStation too, with the right adapter.

Numerous organisations from the disability support community were involved in its design, including AbleGamers, the UK-based SpecialEffect, and Warfighter Engaged, a US charity focused on making gaming easier for injured war veterans. One of Warfighter Engaged’s senior staff members, Dr. Kaitlyn Jones, remembers the call as an opportunity to fix the fiddly DIY aspect that blighted the earlier days of adaptive hardware.

"We were thrilled when employees from Xbox reached out to us, asking us to help them better understand the primary challenges we face when creating custom controllers for players," she explains. "For us, the answer to this was obvious: we were spending large amounts of time cracking open Xbox controllers and soldering out wires to connect the assistive switches and joysticks our players needed for access to the controller’s circuit boards. If we could spend less time working on ways to get the accessible peripherals to "talk" to the Xbox console, we could spend more time on creating innovative yet low-cost buttons and joystick options that people needed to actually play." The Xbox Adaptive Controller, which made connecting an assistive input as simply as plugging it in, was thus "exactly what we needed."

Dr. Jones ended up joining Microsoft in an official capacity, now acting as a program manager on the Xbox Gaming Accessibility team in addition to her charity role. As it turned out, Microsoft had more in the pipeline than just the one controller. They released their own line of XAC-compatible assistive inputs, the Microsoft Adaptive Accessories, late last year, and have recently opened a new and expanded Inclusive Tech Lab in Redmond, Washington.

Replacing the old, 2017-built Inclusive Tech Lab, the site serves as what Dr. Jones calls "a connection point" between disabled computer users and Microsoft’s product teams, where the latter can give advice and take feedback from the former. Appointed with textured carpets and tiling for blind visitors and sound-insulated walls for the hard of hearing, it’s here where devices like the XAC and Adaptive Accessories are developed and tested by the people who’ll actually use them.

Crucially, the underlying aim doesn’t appear to give Microsoft a stranglehold on the adaptive game controller market. The entire point of all those 3.5mm jacks is compatibility with as many third-party buttons and switches as possible, like the Logitech G Adaptive Gaming Kit – a similar concept to the Adaptive Accessories lineup that launched two years earlier, back in 2019. CAD models to 3D-print your own buttons are freely available to download too.

With both highly adaptive and super-specialised controllers available, plus support from nonprofits and corporate juggernauts alike, it might well be true that gaming hardware is more accessible now than ever. Sadly, its issues also extend beyond one platform-locked PS5 controller and some grumpy Destiny players. These include one problem that will be familiar to most buyers of PC gaming gear, but seems cruelly fated to hit people with disabilities the hardest: cost.

Accessible controllers, adaptive or otherwise, are often crushingly expensive. Take the QuadStick FPS: its starting price for a basic, non-Bluetooth model is $549, or about £443. Mental images of a pile of wrecked QuadSticks in Stoutenburgh’s garage suddenly become a lot less entertaining, and according to the man himself, that price tag is just the start of it.

"You gotta buy a mount,” he explains. "You gotta have something to mount to it. So it’s $100 for the cheap mount, which it’s not that bad, I can move it pretty well. But the one you really want is a $250 mount, because it's a camera-type one where you screw this knob and it tightens all the joints so it’s as stiff as possible. So it’s more like $800."

"But I mean, for me, and all the other disabled people in the world, we’re used to it. Everything you need, medically or non-medically is always ten times the price of what it should be for non-disabled people. I need a stylus pen, it’s like $100 bucks, because it's a mouth stylus pen."

Stoutenburgh does add that his QuadStick investments are "worth it" for him personally, but also that there are "definitely" other gamers with disabilities who are priced out of acquiring the equipment they need. Indeed, as much as the QuadStick FPS is an extreme example, almost nothing in this market could truly be considered cheap. The Xbox Adaptive Controller? £75 / $100, 50% more than a standard current-gen Xbox gamepad. The Logitech G Adaptive Gaming Kit? £90 / $100. Among Microsoft’s recommended accessories list is a single 5x5in button for $75.

Stoutenburgh also points out that for all the recent developments with adaptive controllers, players with the most serious disabilities still aren’t being widely served by major manufacturers.

"It basically just comes down to: it's not profitable to them, so they don't care," he says. "When it comes to things like the QuadStick, or people with disabilities with their arms or if you can't use your hands, there's really nothing out there for you to have."

Spohn is similarly forthright: "I think [cost is] one of the primary reasons that AbleGamers has and will continue to exist. These controllers and adaptions are very expensive."

"One of the primary things that we do is facilitate people who have a monetary need to be able to give them the controllers that they need, for free, thanks to our donors' generosity. A lot of what we do is where people are coming to us and saying, 'I know this is kind of what I need, I've seen this other gamer on a video playing it, that's pretty much what is my trouble. So I know I need something like that.' We get to go 'Great, let's figure it out.'"

"Now, the harder side of that comes from where these things are often severely overpriced, on purpose. Some of these places, and I'm not gonna go into libel territory, but they literally told us in off-the-record meetings that they priced these objects at the highest price point that Medicaid will pay for them. And it's because, yeah, it's because they want that insurance money. They say 'Why would I sell this for what it costs to make at $35, when Medicaid will pay $485 for it?' and it's like, well, because you're pricing out people that don't have Medicaid, and won’t pay for it. They want to make a profit."

"It's a shame, it’s why AbleGamers has made a lot of strides towards either working with good partners that are trying to bring the costs down, or even putting out our own products, like the Freedom Wing adapter that we did with ATmakers, where you can make one at home for under $40. You don’t have to pay, you know, $500 for one, and we continue to keep making these adaptions as cheap as we can, because we're not in this to make money, we're just in this to get people to be able to play."

This is no small matter. In 2021, UK median wages for people with disabilities were 13.8% lower than those without, and that’s just for those who can work – many can’t. Whatever the reason, these prices fail to reflect the low incomes of the people they’re supposed to be helping.

Dr. Jones says that Microsoft "absolutely consider cost a key aspect of a product’s overall accessibility," but also that "the development team was faced with difficult decisions in their efforts to achieve the balance between price, utility, and universality that we see with the Xbox Adaptive Controller today."

"We also do our best to support affordability across other aspects of the Xbox Adaptive Controller ecosystem, including things like waiving the Designed for Xbox licensing fee for peripheral devices that meet accessibility and quality guidelines, publishing our “Input spec for makers” that provides the details needed for makers to create their own button and joystick peripherals for Xbox Adaptive Controller, as well as providing direct links to maker organizations and charities who create Xbox Adaptive Controller peripherals at low to no costs in our new Xbox Adaptive Controller User Guide so customers can more easily find these options."

There are other ways in which accessible hardware may not itself be accessible. Jacob Holden, an occupational therapist for SpecialEffect, notes that while adaptive controllers are becoming easier to set up, the process may still be too complex for both disabled games enthusiasts and their less tech-savvy support network. "A lot of these people who we help, often they are dependent on people to help them, like carers and family," Holden explains. "And sometimes, a lot of the family may not have so much of an idea of technology, and how it works."

The 'hub' format used by the Xbox Adaptive Controller or PlayStation Access also aptly demonstrates the catch of having such flexibility: yes, it can support dozens, maybe hundreds of different buttons and switches, but which specific ones are best for a particular user or condition? Microsoft’s Dr. Jones admits that this approach "does put a lot of responsibility on the user to research and invest" in the requisite add-ons.

"We can continue to improve in this space through dedicated efforts to ensure that the wide array of peripherals options out there are easily discoverable and affordable."

It's little wonder that charities like AbleGamers and SpecialEffect have been kept busy. Advising disabled players on the hardware they need is a service that both these organisations provide, as is providing it, with counselling available through in-person or remote assessments. They’re also both regular consultants for the games and hardware industries, building on their work with the XAC; a project Spohn, while critical of big-ticket pricing, still recounts fondly.

"Yeah, that was when a Microsoft employee named Bryce [Johnson, Principle Inclusive Designer for Microsoft Devices] reached out to myself and my coworker, Greg Kaufman, to basically say, 'Hey, there's this really cool controller that we're starting to think about designing, you should totally get in on this on the ground floor.' And we're like, okay, great. And so they pulled us into a Zoom meeting. And basically, they’re like, 'Hey, we want to show you this controller. However, legal says we can't show it to you yet even [though] you’re NDA’d. So, we’re gonna grab this notepad, and they didn't say that we couldn't draw it.' So they started drawing it! It was great. And so we gave them as much as we could, based on their drawings. Then it just kind of evolved from there, where we were constantly in touch point meetings with them for three and a half years of secrecy before the thing even launched."

"It went really well. I think the only thing [that] went wrong was that some people in various journalistic sites, and people who were reading things, kind of got the wrong idea that it was a magic bullet. That, you know, Microsoft released this controller, it had the help of AbleGamers and Warfighter Engaged and other charities that said 'Yeah, it's good.' And that disability was solved. And that's not even true. So a lot of our time afterwards was telling people who desperately needed a mouth controller or Eyegaze or anything else like that, 'Yeah, this is a great controller, but it's not for you.'"

"I think it was great, I'm glad that it came along, and all I can do is between the NDAs that I'm under, and my speculation as a human, say is that I hope to continue to see more new controllers come out to keep serving different segments of the population."

AbleGamers also beat Microsoft to the punch on opening an accessible hardware hub: their Center on Inclusive Play began operating out of their West Virginia HQ just weeks before the first Inclusive Tech Lab opened in 2017. It’s still going, stocked with various controllers and adaptive kits for visitors to try, and features an "engineering area" where new aids can be crafted or printed as needed. Spohn tells me it was inspired by the Centers for Assistive Technology in the US: "If you're disabled and you need a wheelchair, you go to these things called CATs. And you basically get outfitted for what you need for a mobility aid. And there was no such thing for people with disabilities to get into games, so we built it."

SpecialEffect also take a personalised approach, conducting repeated assessments so that players with progressing conditions can equip themselves appropriately as their needs change. They also advocate for better accessibility options within games – Holden cites Sea of Thieves’ addition of 'single stick' controls, where any swashbuckling and/or plundering can be performed using a single thumbstick, as an example of the charity’s successful advocacy. "It's just really nice to see things like that happening," he says.

Broadly, Holden is more positive about how much big brands are doing for accessibility, both with hardware and software. "If you take a look on the Xbox store," he explains, "you've now got accessibility tags. Accessibility has become quite a forefront, particularly with Microsoft, because the accessibility tags allow someone to customise what features they would like to see in a game. I think that kind of ethos, and the Xbox Adaptive Controller, show that Microsoft are serious about helping gamers with disabilities."

"And the same for Logitech and their Adaptive Gaming Kits, where you can use all those switches and the trays to position everything. I think they are starting to see that there are so many millions of people in the world who are disabled, and it's really, really promising that these kind of steps are being taken, and that their voices are being listened to as well."

Holden agrees that some prospective players are being priced out, but stills sees the cost situation as an improving one, given the massive investments required for pre-2018 attempts at accessible hardware.

"I think one of the main things is that it's getting better. Prior to, for example, the Xbox Adaptive Controller being released, there weren't really any major companies doing mainstream accessibility equipment. You had smaller companies, like this one called Letmiss, which were focusing on PS3 games. And their switch interface alone, where you plug everything in, was probably about £300. And I think it's because it was so specialist, and because it was such a small company, that it was literally made to order. That's why those prices have been kind of racked up, and it’s the same with the QuadStick, because it’s such a complicated piece of kit, and just to connect it to another console is also wildly expensive. Same for mounting as well, because a lot of the mounting kit that we use, like the Manfrotto arms, which are typically used as photography equipment, are high standard, really high quality bits of kit."

"But yeah, I think it's all down to these smaller companies that have been really doing their best, but also trying to keep cost-effective, and I guess trying to make a little bit of profit as well, which might be difficult to do. But with the Xbox Adaptive Controller being £75, it certainly made a lot more of a better price range to allow players to actually get involved."

"And the same for the Logitech Adaptive Kit, because it's about £90, and you get 12 switches with it, and a couple of Velcro trays. One of the switches that we tend to use is called a Buddy Button, which are not really been made with gaming in mind – they were made way before the Adaptive Controller was. It was more for the assistive tech side of things. One of those switches alone cost about £45, compared to the Logitech Adaptive Gaming Kit, which is £90... you know, you get two Buddy Buttons in return for 12 switches in the Logitech Gaming Kit. It's a no-brainer, really. I think it's all down to these larger companies actually making that effort to create cost-effective kit, but also kit that is durable, and that is suited for a lot of the players’ needs. The landscape is certainly getting a lot better. There's definitely room for improvements, but yeah, it's certainly getting there."

There are reasons to be optimistic. For one, even if they don’t make as much noise as the average graphics card launch, new solutions for disabled players are coming through. Stoutenburgh has been helping test out a prototype mouth sensor ("kind of like an Invisalign") that, if successfully interfaced with a QuadStick, could allow for more accurate tongue-aiming in shooters. Game devs and hardware manufacturers also continue to seek the expertise of groups like AbleGamers and SpecialEffect, a habit Spohn says is "one of the things that lets me know that we're on the right path."

However, and as it so often is, true change will be slow. Even if companies like Microsoft and Logitech can bring down pricing, it will most likely need to be through new devices that are cheaper to produce. And, as Dr Jones says, "it takes years to create new hardware, often longer to ensure that when we create bespoke accessibility products we do it right."

As for what constitutes "getting it right," one idea gaining traction among advocates and product makers alike is the concept of a true all-in-one controller. One that, in Dr Jones’ words, can be "customized in terms of dimension, mounting position, and more needed to accommodate the wide ranges of strength, mobility, and coordination that players may have." It’s hard to imagine this being very cheap, but in theory, such a device would avoid the need to buy add-on switches, while keeping things simple and self-contained so that families and carers won’t struggle with setting it up. Making it work with any games system, not just PC, would help as well.

"I have spinal muscular atrophy. I've had this disease for 40 years. I know its ins and outs intricately, of my own body, at this point," Spohn says. "And so when I go to get a wheelchair, it's a $48,000 investment to have this machine that helps me cart around. Well, why would I take another device and try to figure out how that one works when I already customized, to hell and back, this machine that already works for me?"

"What if I could just drive up and plug that into an Xbox? Wouldn’t that be a better idea? So this kind of universal technology, this user input, is where we're trying to drive things. Where we can make one controller, and it'll work on an Xbox or PlayStation or a Switch so that you don't need to go through the process three times, you need to go through at one time. And so that's our way of fighting against it."

"The manufacturers – and I don’t mean Xbox, I mean the people who are trying to rip people off - want these different adapters to be sold for different places. We want to make one device that fits for multiple things. That way, it keeps the cost down, and it lets people continue to play for years to come."

Such a holistic device may sound fantastical, given the web of commercial interests that would inevitably be involved, and it could invite more of the same "magic bullet" misunderstandings that the Xbox Adaptive Controller unintentionally did. But the underlying logic is sound, and there’s no clear technical reason why a more adaptive controller couldn’t exist. Still, to make this universal approach a reality (and keep it genuinely accessible), relying on charities won’t be enough. More well-resourced manufacturers will need to do actually start caring – not just about profits and platform exclusivity, but about the games enthusiasts that they could be better serving.