Why the mysterious love affair between video games and giant elevators may begin with Akira

Where did they come from? What are they for?

It’s funny how some aspects of game design are so ubiquitous that we stop questioning them, or even noticing them. After decades spent playing video games, I know that if I look behind the waterfall, there’s likely to be some sort of shiny goodie to collect. If I head left rather than right at the start of a level, I’m bound to find a juicy secret. There are conventions. Traditions. I can’t remember a time when games didn’t have giant lifts - and yet, I’m not entirely sure why they’re there. I’m not talking about the regular kind of lifts that you pile into, usually at the end of a level, to transition from one part of the game to another; those ones have historically been used to hide lengthy loading times, like the interminably long lifts of Mass Effect.

What I mean is the lifts that are essentially tennis-court-sized moving platforms, usually with little more than a flimsy guard rail around the edge to stop elevator enjoyers from plunging down the shaft. Even more specifically, I’m talking about the diagonally moving elevators that trundle slowly into the depths, often to some nefarious laboratory. There’s a good example in the Resident Evil 2 remake, where you fight the final boss on an inclined elevator as it slowly, ever so slowly, descends towards the train that will grant your escape. So where did these giant elevators come from? And why do developers keep putting them in their games? I set out to answer both questions, and went somewhere unexpected.

First of all, I wondered whether anything like these enormous, open-plan lifts exists in real life, and I got in touch with a company called Niche Lifts to ask them whether there was any real-life equivalent to these huge, diagonally trundling platforms. Surely if anyone knows about this sort of thing, I thought, it’s a company called Niche Lifts. They humoured my bizarre inquiry with a response, saying that the closest thing to what I was describing were funiculars - something I’m familiar with. There’s a spectacular Victorian funicular railway in Saltburn-by-the-Sea, not too far from where I live. The Saltburn Cliff Lift has been trundling up a 71% incline from the beach to the clifftop since 1884.

There are loads of these rickety cliff lifts dotted all over the world. The modern equivalent of these is probably the incline elevators that have been popping up at underground train stations. But funiculars and incline elevators aren’t quite what I’m looking for. Big lifts do exist in real life – like the huge freight elevator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, which is used to haul things like trucks, cars and train carriages for display on the upper floors - but they’re all safely enclosed and stubbornly vertical. The closest thing to a classic video-game giant lift is probably the Three Gorges Dam ship elevator in China. It’s the biggest elevator in the world, but it’s also distinctly wet, and definitely not diagonal. So where did all these diagonal game elevators come from?

Diagonal lifts have been a feature of video games for a long time. One of the earliest I can find is in Konami's 1989 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arcade game, in which the final stage sees the Turtles descending on a giant diagonal elevator in Krang’s Technodrome base. There are earlier games featuring lifts, of course – like the 1983 Taito game Elevator Action – but Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is the first one I know of to showcase a big diagonal lift. (Please let me know in the comments if you can find an earlier example, I genuinely want to know.)

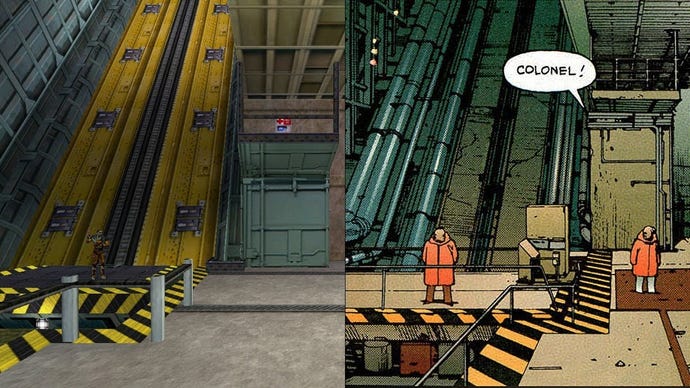

Massive diagonal elevators have cropped up frequently since then, in games like Metal Gear Solid, Time Crisis, Final Fantasy VII, and the often overlooked PS1 classic Silent Bomber. Perhaps most notably, one of them turned up in Half-Life in 1998, and more than one person has noted that the diagonal elevator in Half-Life almost exactly resembles a diagonal elevator featured in the manga Akira, right down to the yellow and black hazard stripes. I contacted Brett Johnson, the designer of the Half-Life elevator, via LinkedIn, and he confirmed that he was inspired by Akira.

So I got in touch with Matt Alt - author of the brilliant book Pure Invention, which is all about how Japanese innovations and pop culture have influenced the world - to ask if these kinds of elevators appear in manga before Akira. “I'm not sure if Akira is the first but it has to be the most well known,” he replied, although he suggested a 60s manga/anime series called Tetsujin 28 (Gigantor, in American translation) that centres on a giant WWII robot, repurposed by a young boy for crime fighting, and which was a huge influence on Akira. “I am not sure if incline elevators appear in it," he told me, "but I wouldn't be surprised...”

Alt also pointed out that it’s extremely common for video games to take ideas from manga. “The thing about games, particularly Japanese games, is that they exist in a symbiotic relationship with manga and anime. When I spoke to Uemura-san, the engineer of the NES, he said ‘Once hardware developed to the point where you could actually draw characters, designers had to figure out what to make. Subconsciously they turned to things they’d absorbed from anime and manga. We were sort of blessed in the sense that foreigners hadn’t seen the things we were basing our ideas on.’”

So it's possible we can draw a direct line from Akira to every giant diagonal lift in video games. In fact, when I put a callout on Twitter asking game developers to tell me about giant, diagonal elevators they’d worked on, Rich May, a lead programmer at Rebellion, immediately responded with: “Ahh, the obligatory Akira lift!” So do game developers actually call them Akira lifts, then? “I did a straw poll of my colleagues to see who also referred to them as that,” said May, when I interviewed him over Zoom. “I think it’s an age thing. If you grew up in the 90s, like I did, and Akira was a big touchstone of your childhood, then the term Akira lift almost immediately brings up that that concept." Several people, May said, knew exactly what he meant by "Akira lift", while quite a few looked blank, and a lot of the younger people he worked with "didn't have any idea what I was talking about all, which is always a bit depressing. But there were several people who were like, ‘Yep, I know exactly what you mean’.”

An Akira lift features in the 2016 Rebellion game Battlezone, slowly raising the player’s tank into the battle arena. “It was intended as a sort of introduction to the game,” May said. “So you get gradually released into the environment.” The original idea was that several players would all ride together on the lift, and be able to move and look around. But this proved too technically challenging, so in the end the lift carried just one player, locked in place. Actually getting the lift to work was tricky, too. May explained that in terms of physics, the player was left at the bottom of the lift shaft, while the camera and the rendering position of the tank simply moved upwards with the lift. Then when the lift reached the top, the physics component was teleported to the top of the shaft. “That was one way you could avoid problems where you've got things moving out of sync with each other,” he said. “Classical errors you'll see with lifts in games involve things like, say, if you drop your gun or lob a grenade or something on to the lift, you'll often see those fall through the lift or jiggle about on the lift because they’re moving under physics and the lift is hitting them continuously.”

It sounds like lifts are pretty tricky things to implement. Are they as hard as making doors, say? “They have a lot of similar issues, I suppose,” said May. “There are some similarities with being trapped by a door: you can be crushed by a lift, and you have to resolve that in some way. Does the lift stop? Does the player die? Does the lift just sort of move through as if you're a ghost?” He added that there can also be all sorts of problems when shooting or throwing projectiles when stood on a moving lift, since the game would have to take into account the relative velocity. If you throw a ball on a plane, you'd expect it to behave in a similar way to throwing it when stood on the ground. But if it was in a video game, and the ball didn’t ‘know’ it was already moving, it would zip through the passenger cabin at several hundred miles per hour.

So why put something that hard to make in games in the first place? May can think of a few reasons. “There's the classic one, which is just a kind of gameplay break for the player,” he said. “You used to see that in things like sideways brawlers. You'd fight in a little arena for a few minutes, and then move on.” Then he added the technical reasons: “They give you an opportunity to segue between two different sections of a level without having to keep it all in memory.” In other words, just like those dreaded Mass Effect lifts, giant elevators also mask loading times. Once the lift starts moving, the previous level section can be erased from the computer’s memory and the next section can be loaded in.

“It's about like, ‘Oh shit, we're going down somewhere really scary’.”

There’s also the increasingly common scenario where the lift is a whole level in itself, a dynamic platform that moves through the environment while enemies plunge aboard, challenging you to fight in tight corners. Perhaps one of the most common uses of giant diagonal lifts is to build anticipation, taking you ever upwards (or ever downwards) towards some terrifying reveal or climactic battle. “That is what that lift is all about in Akira,” May noted. “It's about like, ‘Oh shit, we're going down somewhere really scary’. That's why they've got all this massive infrastructure: there's a reason why he's kept at the bottom of an enormous shaft.”

But perhaps there’s an even simpler reason to include a massive diagonal lift in your game: they look really cool. And the fact that nothing looks like them in real life surely only adds to their allure. Plus, as a shorthand for indicating that you’re about to enter a messed-up and nefarious sci-fi laboratory, they're right up there with twitching bodies in glass chambers full of green liquid. Then again, perhaps they’re not as fashionable as they used to be in the days when Akira reigned supreme in the collective nerd consciousness. After all, RPS readers recently said they preferred elaborate corridor architecture to funicular fights.