Wot I Think: Sherlock Holmes - Crimes & Punishments

The Grating Detective

In publishing these short sketches based upon the numerous Sherlock Holmes games from Frogwares, it is only natural that I should dwell rather upon their failures than their successes. And this is not so much for the sake of their disreputation – for, indeed, it was when I was at my wits’ end that my energy and vitality were most miserable – but because where they failed is where one should not spend one’s money. And this one’s rubbish. Of Crimes & Punishments, here's wot I deduced.

With two concurrent contemporary adaptations of Sherlock Holmes taking place – Moffat’s awful Sherlock, and Robert Doherty’s silly but splendid Elementary – it could perhaps be a pleasant treat to see someone exploring the character in his original setting. However, history has somewhat shown that this someone should perhaps not be Frogwares. Since 2002 they’ve been releasing an onslaught of particularly dreadful Holmesian adventure games, the first decade’s worth only fondly remembered for the terrifying teleporting abilities of a blank-faced Horror-Watson.

However, having given up on the series myself, Adam – with hefty qualifications - somewhat enjoyed the previous entry, so it was with renewed hope that I began Crimes And Punishments. I fear that - while an obviously vast amount of work went into this enormous game - any raise in standards hasn’t been maintained.

If you’re seeking the unifying theme that brings together these latest six episodic tales into a single game, so am I. Six unremarkable, utterly disparate tales, of wildly varying lengths and complexity, tell the sorts of stories you might imagine Doyle would have conjured on an off-day (quite a compliment, I assure you – most attempts to write in his style are usually far more disastrous than these). That they somehow have the cruel husband who might have been murdered by a suffering wife twice in six stories perhaps betrays how close they are to running out of steam, but it’s a far more sedate and sensible outing – there’s no Jack The Ripper, or allusions toward vampires, and so on. Mundane might be another word.

The series has always seen fit to play out the styles of an adventure game from a 3D third/first person perspective. Here once again you can choose to view over Sherlock’s shoulder, or through his eyes, but neither is close to good. The camera gloopily swings around, creating a gory motion sickness via a seemingly impossible combination of sluggishness and over-sensitivity. Running, which is vital if you’re not to expire of old age before finishing the game, has a treaclish staggered start, awful in first-person, repulsive in third. And the button to run constantly – and bewilderingly - changes its behaviour. Sometimes you must hold down Shift to run. Sometimes you must press it once to run. Sometimes you must press it to walk. When is arbitrary, and changes at random within scenes.

Interactive objects must therefore be faced, rather than simply clicked on with a mouse, meaning Sherlock instantly becomes a bumbling madman who must stand square to, and press his nose up against, a wall in order to look at a painting. Oh, and it starts with an attempt to be a cover-based action game, as Watson attempts to avoid a blindfolded Holmes’ gunplay.

Other mini-games that grace us along the way include a repetitive and tiresome lock-picking puzzle, playing as Toby, Watson’s dog, following scents, arm-wrestling, fisticuffs, and taking someone’s pulse. All are uniquely awful. There’s even the preposterous appearance (thank goodness twice only) of a scent-identifying puzzle in which Holmes must rotate 3D patterns until they form a vaguely xenophobic shape that identifies the smell. However, these are asides, and can mercifully be skipped via the space button if you momentarily feel above trudging your way through restoring a torn photograph, or picking your seven-thousandth lock. Required are the many mini-game-things that constitute Holmes’ main detecting palette.

The first appearance of Holmes’ extraordinary deductive skills appear when you’re told to press T to enter a mode in which the graceless detective can spot the details ordinary folk might miss. This is in black and white, because that makes sense. The first detail you’re asked to spot that mortal man cannot? Some footprints, that a police officer is currently looking at through a magnifying glass.

Click on the footprints and it zooms in for a closer look, where your task is to magnificently click on the footprints. It zooms in again, and the genius mind of Holmes informs us, “These footprints appear to be quite large.” Where would Scotland Yard be without him?

Concluding a case brings the game to its most numbingly farcical. There are a few suspects, and evidence suggesting the guilt or innocence of each. You’re asked to connect up neurons in Holmes’ brain (no, really) to form conclusions over who is guilty, based on making black/white choices over various clues. But these choices are gibberish. Someone dropped a tobacco pouch at the scene of the first crime – the murder of a former sailor, skewered to his shed wall by a whaling harpoon. You learn to whom the pouch belongs, but on nothing whatsoever must conclude whether the presence of the pouch itself proves guilt, or is merely circumstantial. It’s not until you decide definite guilt that it will allow you to connect this with other evidence, to allow you to, well, conclude that he’s guilty. It’s just incoherent. And becomes ever more so as it progresses, attempts to add complexity, false endings, and contradicts itself.

Which is a shame, as in principle it’s a rather nice way of conducting the investigation. Make connections between clues, then between the conclusions formed find further connections, until the weight of evidence points to one person. But because the game wants to be able to offer multiple conclusions to each crime, its need to let you form incorrect patterns, to find others guilty, means it by nature needs to leave it all ambiguous. Instead of actually investigating, asking pertinent questions based on your conclusions, or interrogating people to the point of eliminating them as suspects, the game allows none of this and demands semi-educated guessing.

Accuse a suspect and you’re then presented with two further options – to condemn them as a cold-blooded killer, or to suggest extenuating circumstances, even help them cover up the crime (which is a welcome inclusion in the series, since it was a frequent ending in Doyle’s stories). It then allows you to go back on that choice and replay the ending, as often as you wish, until you get the “right” one.

As things go on, this gets more opaque, and more ridiculous. The second chapter is entirely predicated upon a universe in which railway stations wouldn’t appear on a railway station map. In the third, the murder weapon is made of one of two substances. Which one the game considers “correct” is never explained, and is in fact utterly contrary to all the available evidence.

The third and fourth chapters are dramatically shorter than the first two (even accounting for the possibly extended version of the fourth), concluding long before you’d imagine. The penultimate is longer again, and deserving of a quick aside.

It’s about the murder of the director of Kew Gardens. Which is an odd choice. Using a real, renowned place (for which I have no particular affection) is strange, possibly intriguing. But diminishing it into a series of potting sheds, run by apparent idiotic amateurs, seems a bit, well, inappropriate. Kew at the time (1894) was under the directorship of William Turner Thiselton-Dyer, having previously been run by William and Jospeph Hooker – three of the most important botanists of all time (I checked). It seems peculiar to engineer a hokum fictional past, with an imagined director who was an unpleasant drunkard and bully who knew nothing about plants, running the place with abundant corruption and moral iniquity. Especially as they could just as easily have written a fictional gardens. I’d imagine Kew won’t be too delighted about it. Indeed, not the most serious matter, but still seems interesting to ponder.

Amazingly, this chapter then swerves into portraying the most stereotyped Chinese character since Big Trouble In Little China, complete with “Ah-so!” accent. That Holmes stops short of trying to order from him some “Egg flied lice” feels like a miracle.

Then the final is a middling affair of no real impact, with a sudden utterly ridiculous fifty-fifty choice of impossibly enormous consequence to make at the end.

Most grating is the technological mess. The developers appear to have poured slow-drying cement into the Unreal Engine. Everything’s so agonisingly slow. Even dialogue options crawl back and forth to highlight as you mouse over them. It’s like wading through thick soup.

Great long stuttering loading scenes pop up every time you switch between one one-room location and another. Which wouldn’t be so enormous of a problem if the game didn’t incessantly send you back and forth to say literally a single sentence to someone in one place, then another in another, then back to the first, over and over and over. There’s no sense of flow. Conversations with characters feature a list of sentences to click through over a close-up of their face, but it needs to fade to black and return to the exact same face each time they respond, at the beginning and end of every sentence.

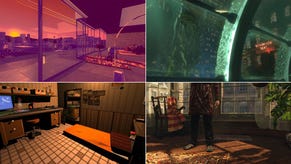

It’s remarkably attractive – locations can often be enormous, and are invariably beautifully crafted. Over the six chapters you visit a great number of places, and even those only popped into for a moment are meticulously designed. And the characters, while certainly waxworks, are particularly good waxworks. There’s some really nice use of textures, very realistic skins, blemishes, and details. (Which are relevant to a particularly fumbled part of the game where you must look at various features of characters' faces, clothes and bodies to discern things about them. It should have been a highlight, to be able to Sherlock it up, but it’s either forgotten or used like a heavy mallet.) But it all feels so wasted, since you’re viewing it all from the dreadful gooey movement and the frustration of having to pick through its detail to fluke upon standing near the one or two pixels with which you can interact.

The voice cast sound like an amateur dramatics society, doing the voices they remember seeing on the telly in the 70s. But over time, perhaps with Stockholm syndrome, I began to enjoy Holmes. Watson is barely used, and reduced to the boring role of being alternately dismissive or astonished. But then Sherlock Holmes keeps his chemistry instructions written in riddles. “The yellow reagent must be added three reagents after the blue reagent. The silver reagent must be added after the yellow reagent.” So I hate him overall.

There is clearly an enormous amount of work here. Not only is it interminably long, but huge effort has gone into getting the tone of the writing (if not the actual content) right, the locations lavishly crafted, and the murders possible to solve in myriad ways (to no overall effect – I’ll dispose you of that hope). Sadly, I thoroughly did not enjoy playing it. The excruciating pace, the meandering drivel that makes up most of the conversations, and its dreadful mess of load times within load times, would try patience even if the stories being told were worth it. As it is, they’re provincial affairs of no great genius or surprise, deduced by inevitability and guesswork, rather than deductive reasoning or inspiration. So, so much effort has gone into this. But sadly, to little entertaining result.