Wot I Think: The Banner Saga

For the ages?

The Banner Saga is a tantalising prospect. An independent release from a small team of former Bioware employees, it promises a rich story, a new world and intricate tactical combat. It also has the most stupendously attractive art I've seen in a long time. Impressed by the opening hours, I've since spent several days in the game's icy company, I've deliberated long and hard to bring you my final verdict. Here's wot I think.

A short time past the half-way mark of The Banner Saga’s campaign, one of the few characters willing to offer any exposition asks the party’s current leader, “How well do you know history?”

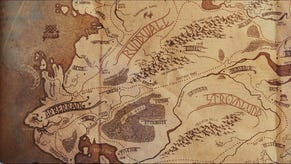

“We’re from a very small town in the woods”, he replies. Despite the distance travelled, the size of the map and the apparent complexity of the world’s history, the path from that small town to the world’s end (whether place, moment or pub) is related as a series of similar waypoints. If the saga were woven into a banner a thousand feet long, most of the space would be taken up with the same stitched scenes. Battles against the same few enemy types are repeated, if not quite ad nauseum, at least ad queasium.

During The Banner Saga’s campaign there are four types of shot - the attractive isometric battlefields, the handsome and mostly static dialogue scenes, the beautiful settlement views and the gorgeous profiles of the player’s caravan travelling across the world. The unifying quality is the artwork, as may already have been obvious if you’ve seen screenshots and videos of the game.

Almost any still plucked from the game could be mistaken for a cell from an accomplished animated film – the detail and craft of the work is luxurious, and the character and creature designs happily deviate from the usual fantasy RPG fare. Even the finest stitching cannot save an Amazon’s leather thong from ridicule, nor dwarf’s braided beard from the swamp of cliché.

There’s none of that here though. Alongside the men and women of the world, there are Varl and Dredge. The former are immortal horned giants and the Dredge are the Other. While Varl and man live in an uneasy peace, mostly living separately, the Dredge are an occasional blight in the world’s history, an ill-understood invading force of rock-like humanoids, flinty and naturally armoured. They’re the worst noun to pick when playing twenty questions – mineranimals maybe? – and as the campaign plays out, details of their existence are revealed, through historical and personal tales. In the bleached-white days that may be their world’s last, every culture and individual realises its strength and its shame. Everybody’s someone else’s freak.

The Banner Saga’s best moments are in the unpicking of its strange mythology. The lack of immediate exposition threw up a divide between John and me during our preview verdict. I admire the game’s faith in my ability to pick up the pieces of its narrative, which begins in media res and then splinters as new perspectives are introduced. I still find the (few) shifts from one group of protagonists to another uncomfortable but that’s an issue of pacing rather than confusion.

Pleasingly, the confidence I felt in those first few hours was rewarded. The storytelling finds a balance between mystery and meaning, balancing the local family histories emerging from the player’s caravan of refugees with mythological tales of cosmic significance. This is a saga that begins with the sun frozen in the sky and the gods long dead, although the memory of their existence is as real and true for the people of Stoic’s world as the memory of Pulp is to me. Their influence has not yet waned and monuments to their power litter the land.

It’s tremendously exciting, to be shown such a glorious new world to discover, but sadly, the journey becomes a trial long before the end. In tactical RPG fashion, the player is led from one fight to the next, with dialogue scenes breaking up the turn-based combat. There’s a management aspect to the game as well – as the caravan crosses the map, decisions must be made, affecting morale, supplies, relationships, and the number of survivors available. I call them survivors because this isn’t a game about taking the fight to the enemy and leading an army, it’s a game about preservation.

The caravan is made up of refugees and each new settlement that it reaches presents dilemmas. Some people will want to turn you away when you need to restock food supplies, others will want to join, their lands barren, adding the burden of extra mouths to feed. Managing the desperate and the dying certainly makes a change. There are acts of heroism in The Banner Saga and moments of earth-shattering enormity, but it’s the quieter moments that stick with me.

And then there’s the combat. The system is clever, with several tweaks to the usual grid-based biff ‘em up that make the early hours a gripping ride up the learning curve. And then the curve straightens out, but instead of following up with an exciting plunge into new depths or a series of loops and banked turns, The Banner Saga settles into a too-comfortable rhythm.

I readily admit that playing in a few long sessions, as I did, may contribute to the feeling of enduring rather than enjoying the latter half of the game, but even if I’d consumed it in a more piecemeal fashion, the lack of variety would have worn at my patience. Those four shots – the journey, the dialogue, the tactical field, the settlement – cycle with minor changes. The travel scenes are consistently the loveliest images of snow, forest and mountain outside a National Geographic spread, but they’re cutscenes. Stunningly attractive cutscenes, sure, but they’re the moments in between the tactics and the management.

As for the dialogue, it’s well-written and there are distinct voices with their own portions of a wider story to relate. The world-building, following a confused beginning, is superb, and the environments, characters and mythology are so artfully crafted that I wouldn’t advise against a journey through the fading splendour of it all. It’s just that this particular journey becomes something of a slog.

On the map, which is packed with succinct yet detailed lore, each settlement seems unique and each forest, mountain and coastline has something to recommend it to the visitor. However, strip away that flavour text and references in the dialogue, and there’d be very little to differentiate them from one another. Occasionally, when stopping for supplies or conversation, there’ll be a specific hotspot to click, a way to continue the story, but otherwise there’s an upgrade screen, a market and a training ground for mock battles. Like a touring musician, the player swiftly discovers that one town is much like another when reduced to a stage and a hotel room.

Battles are much the same. The limited enemy types and battlefield layouts mean that tactics may take a while to discover but can then be applied again and again. Changes come when a tougher variant of a certain foe is introduced, or a new character joins the party, but the intricate intelligence of the turn-based mechanics aren’t exercised as much as I’d hoped. The clever split between armour and health, and the use of willpower as reward and in-battle currency promise more than they deliver. Perhaps multiplayer brings out the best of the system.

The main tactical consideration in any Banner Saga combat is control of space and awareness of the difference between armour and health. Dredge splinter when they receive a solid blow so an essential tactic when fighting them on all but the easiest difficulty level (can be switched during a playthrough) is to herd them, creating a domino effect. Initial damage should be to their armour rather than their health, as the former is the higher number and reduces damage to the latter. However, chipping away at health reduces the damage that an enemy can inflict and in rare cases it can be helpful to switch a previously successful plan around a little.

Those rare cases are few and far between, however, usually arising as part of battles that are boss fights in all but name. Mostly, there’s a routine exchange of ranged attacks, a manoeuvring into position and then a series of clubbing blows. Aim at the right enemy at the right time and you’ll mostly come out on top without flexing your brain too strenuously.

Preparation is often more important than the battle itself but, again, gear and skill choices are limited. The same currency (renown) is used to raise levels, buy equipment (simple stat-boosting stuff) and secure supplies. On top of that, increases for higher level characters are more expensive than those for lower level characters, meaning there’s an implicit encouragement to lead a party of averages. On medium or hard difficulties, injured warriors suffer a reduction to their stats for several days so cycling the active roster is essential, and that adds tactical depth to the game. It’s punishing, however, to find yourself reliant on a level one eejit during a climactic battle simply because everybody else is hurt and the renown that would have improved his skills was spent on food and equipment.

There are often too many choices that seem somewhat arbitrary and not enough that seem to provide the player with real agency. I eventually found myself leading a band of a hundred people or more across the cracked and frozen remnants of an evaporated lake, with no food or mead to share among them. Every day some would die and morale was rock bottom. But, I the end, none of it seemed to make a difference. We reached the other side and continued on our way.

Occasionally, a fight larger than a skirmish breaks out and your numbers are pitted against those of an enemy. It’s possible to join the fray, in yet another turn-based battle, to tip the tide in your favour. It’s even possible to fight a second turn-based battle when the first is won to protect your soldiers even more. Hours before the end of the game, I was skipping them and taking the losses on the chin simply to avoid repeating the same (or very similar) sessions again and again.

Despite all of my gripes, I enjoyed at least half of my time with The Banner Saga enough to have come away from the experience with fond memories. It’s a shame that where there should be urgency and drama, there is instead an unforgiving slog through a world of fading splendour. I found the hardest difficulty too frustrating but would recommend playing on normal rather than easy – even though there are difficulty spikes, overcoming them brings about a surge of satisfaction that is entirely lacking when every fight is a walkover.

But, good heavens, it's such a beautiful creation, and what is beautiful in it is often quietly subversive.

The heroes’ journeys in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy are catalogued in a regular series of wide-frame long distance shots. As well as pleasing the New Zealand Tourist Board, the footage of actors and their stand-ins striding across landscapes was short-hand for the days and miles that were passing, demonstrating the commitment and endurance of the Fellowship and, later, its fractured elements. Though they were all reduced to dwarves (and the hobbits and dwarves to baby dwarves) by the mountains that held them, those long shots also served as a reminder of their undertaking and the strength that they required to shoulder it.

In a twisting of a similar perspective, Stoic’s vision reduces those ‘hero shots’ to a rabble led by a fragile banner, carrying families, histories and entire cultures in its wake. Broken carts creak and clatter. It’s a picture of vulnerability and a different kind of strength, and at its best the game is about that as much as it’s about stats and tiles. It’s a shame that, in this instance, the world is more fascinating than the somewhat cumbersome game that inhabits it.